Work samples

-

The Map

The MapThe Map asks the viewer to visually link disparate shapes and materials to conceive of a whole object. The shapes were generated from a garment drafting process, and then made material using sculpture and jewelry making techniques. The Map was begun during the first Trump administration, and is ultimately a rumination on the intersection of history and personal and collective insight.

-

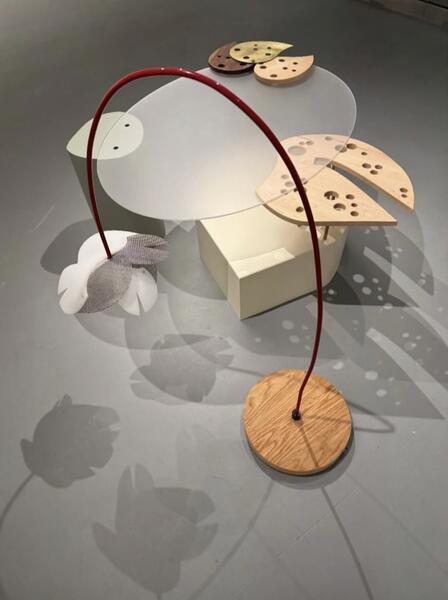

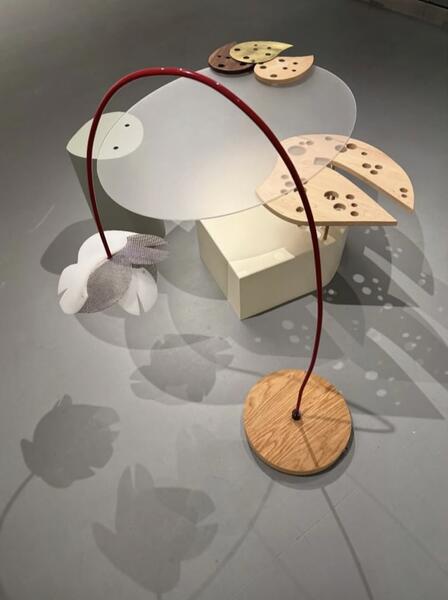

Catch Table and Fishing Lamp

Catch Table and Fishing LampThe Catch Table and Fishing Lamp are the first pieces made for a collaboration with Koba Furniture, ARROWSPACE X KOBA. The shapes used in these designs were generated from a pattern making process used for garments, and then explored through a material lens afforded by my experience with jewelry making.

Testing an idea that objects are frozen moments in time, I hoped to create a sense of dynamism. In design contexts, it asks the client to participate: the forms that make up the base of the table can be arranged in a few different ways, and the wood details on the top are movable even after installation.

(Photo by Amy Boone-McCreesh)

Available for Purchase -

A Dime A Dozen

A Dime A DozenAs I combine my shapes into various compositions, a narrative about landscape is emerging. Here I imagined fishing in a murky pond; that moment when you catch something and you are unsure if it's a boot, or a fish, or a piece of trash. You won't know until you name it.

I worked with Dave Greber, who helped me capture my shapes in a projection mapping software. We presented them in such a way as to cast doubt on material reality. The shadows, the reflected light, and the movement all work to remind the viewer that they don't ever quite know what is real.

In motion: https://youtube.com/shorts/J7U4bQPctjU?feature=share

About Elizabeth

Elizabeth English is an artist, designer, and educator who lives and works in Baltimore Maryland. With a background in architectural design, and a long career working with historic buildings, Elizabeth now investigates how built objects of every kind can tell stories. Inquiries into history, theory, fabrication processes and collaboration all lead to deep examination of the construction of the material world and our place in it.

Her interdisciplinary approach ranges from furniture and… more

The Map

In my practice, The Map marked a transition from making design to making art. I have always been interested in history, and had given myself the task of studying it through visual engagement rather than through textual analysis. Begun during the first Trump administration, The Map started with a curiosity about the late Rococo and early Enlightenment. The seeds of everything that had gone awry in the 21st century were in that time period; could I learn more about the origin of the problem if I focused my inquiry on a visual artifact?

-

The Map

The Map -

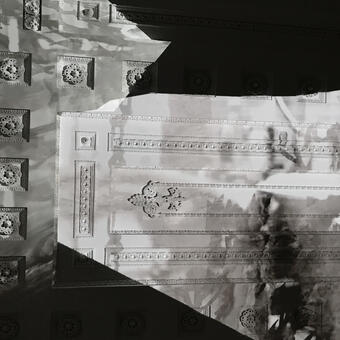

Map of Versailles, 1765

Map of Versailles, 1765When I study history in this way, I try to choose images that hold some unspoken fascination. Looking at this, I was, and still am, drawn in by the translucency of the color, the delicacy of the mark making, and how those things combine with a map as an expression of "fact". In many ways it's a perfect image for the time period. So many contradictions are implied: pastoralism versus absolutism, delicacy paired with authority. Reason paired with romance. Unobstructed beauty owned by the few. Property owned at the expense of who? I knew that in a few short years from its making, this place would no longer exist in the way its map maker had conceived it. Yet in 21st century America, these contradictions were still playing out.

-

The Prospector

The ProspectorI'd spent my career drafting architecture, and for this project, turned those skills to drafting for the body. This is the first in a series of figures that when grouped, tell a story of exploration, crisis, and re-emergence. Couture drafting techniques allow for a precise fit, and speak to the rich visual and decorative arts culture from which the 1765 map emerged.

I plan to return to the figures, but at this moment, I became intensely interested in the pattern detailing on the side of the body. I drew it in response to the map; how land was divided, what was surface, what was beneath, what was beautiful, what was awful. I had just finished treatment for breast cancer, and realized then that a facet of my inquiry was existential. These pattern pieces had a story to tell, beyond and in addition to the historical one.

-

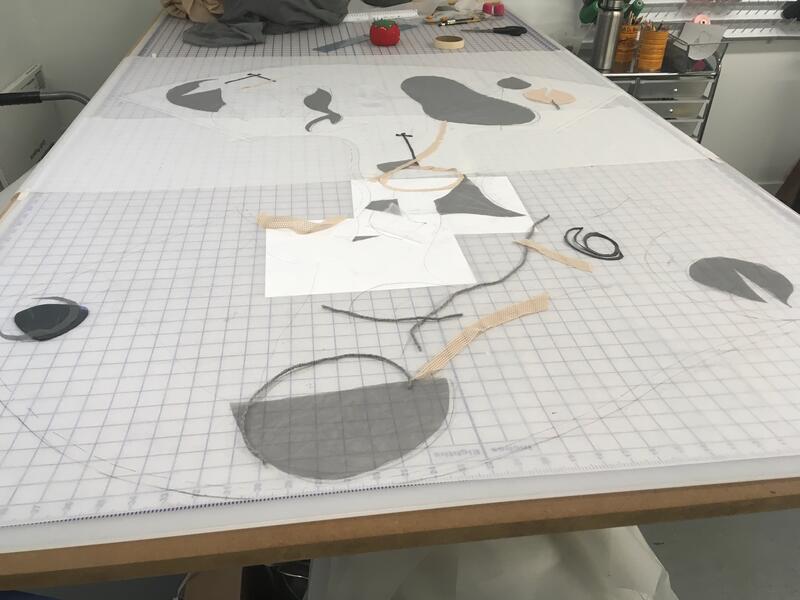

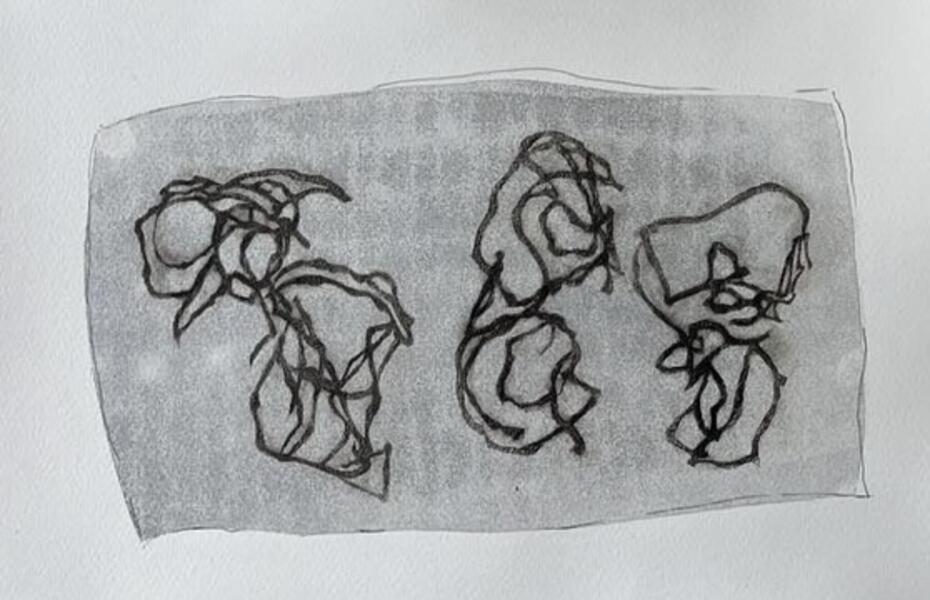

Pattern pieces as narrative

Pattern pieces as narrativeSearching for meaning in the drafted shapes, I began to do what any designer would do. I looked for clues in spatial associations. I took the shapes generated from the garment drafting process, and scattered them into compositions to see if they could yield a new understanding.

-

Relationship to the body

Relationship to the bodyThis spatial solution, with pieces scattered behind, yet being dragged forward, suggested destruction, fate, the pieces we must work with- our past and therefore the elements of the future we must build.

-

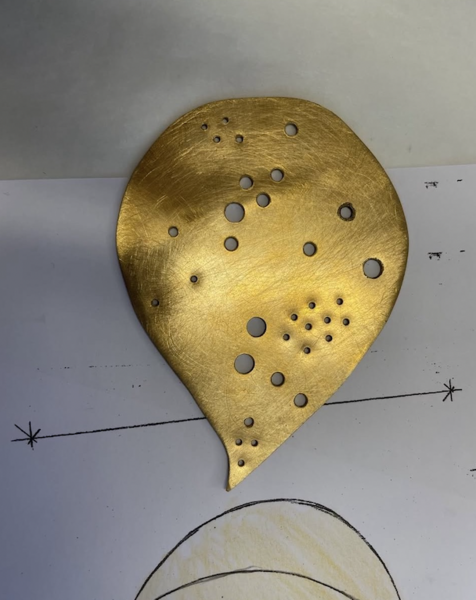

Shapes as conceptual elements

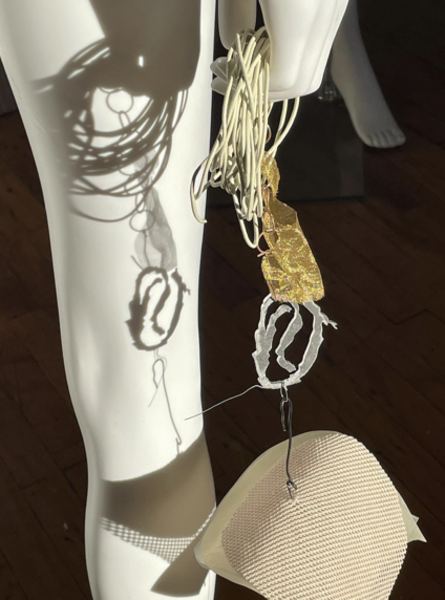

Shapes as conceptual elementsNow that I had a provisional understanding of what the shapes were, a material language began to evolve. Expressed in materials, the shapes began to point to a personality. I wanted them to evoke luxury, skin, bondage. I wanted to disconnect the material references from any moment in time, so that they could be as relevant as possible to any inquiry or set of assumptions about contradiction and narrative. The goal was to remain open and beautiful, if somewhat frightening- like the 1765 map.

-

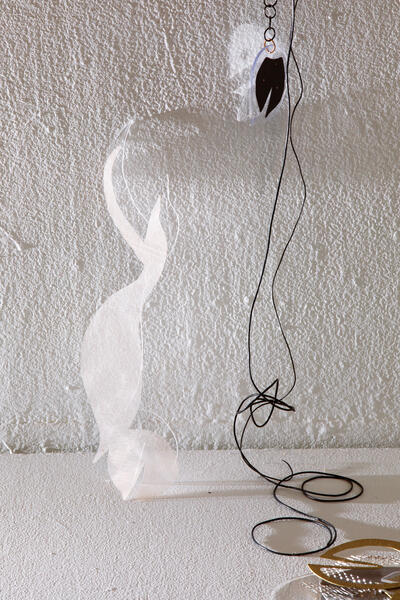

Elements of a whole

Elements of a wholeNow that I had a "function", and a material language, I began to work on refining the piece. I found the mannequin distracting, and instead chose to install the chain at hand height, suggesting that the viewer could easily pick it up. If this was indeed a stand in for fate/future and the elements of past and present that make it, the shapes do belong to everyone to take in hand. This is true from a political stance and from a personal one.

Designers are frequently interested in what makes something a "thing", and I am no different. I got curious at this point about the expandability of the piece, and the fact that it could be read as a whole even though it wasn't connected. It became an experiment testing Heidegger's concept of the Thing, and of Derrida's understanding of possible emergent events. Ontology is something that preoccupies my entire practice.

-

The Map, detail

The Map, detailA map is something that is supposed to make a claim for meaning and set one truth above others. From this vantage point in history though, we see how fickle meaning can be, both in socio-historical terms and in personal terms. In the final work, the loose construction suggests the sensuality of the Rococo, but also reveals its unresolvable tensions. Shadows matter as much as conventional materials. Connections are almost irrelevant. However, the elements that make up that mapped meaning are concretely identifiable. It is up to us to arrange them in such ways as we see fit.

After a moment of crisis, how will we pick them up next?

(but a storm is blowing in from Paradise)

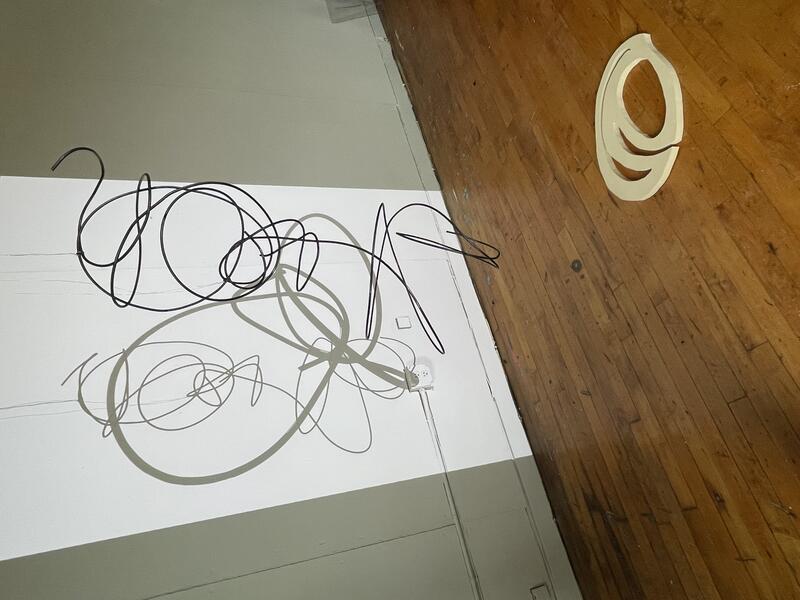

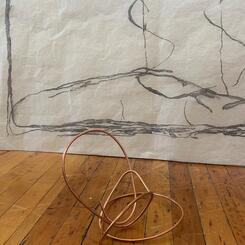

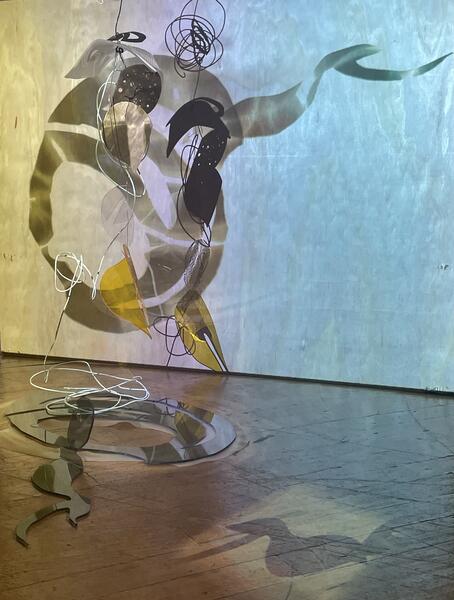

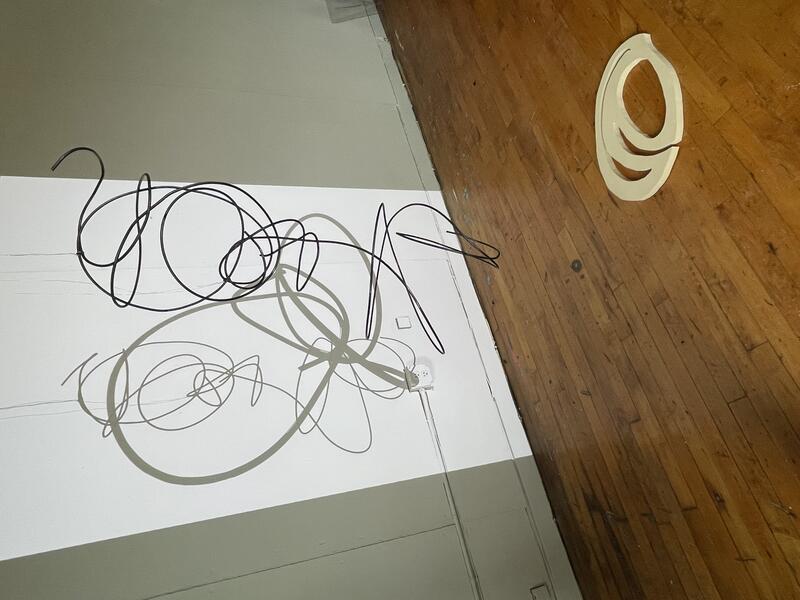

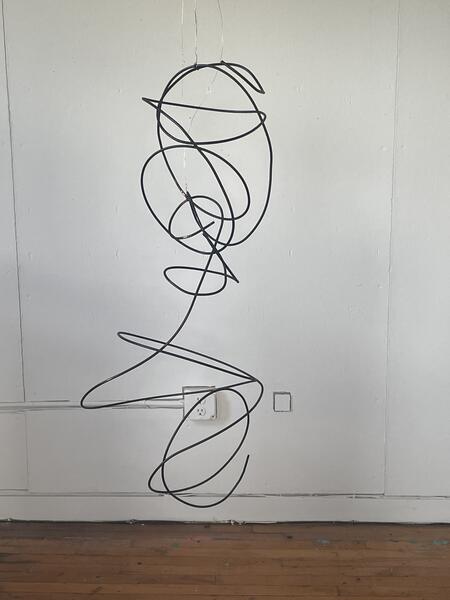

(but a storm is blowing in from Paradise) is the result of a few different inquiries. One has to do with history. One has to do with the language of landscape: maps, weather, and perspective views on the horizon. Another path of inquiry is about testing the ability of simple gesture to communicate. A fourth path is concerned with objects and how they are defined.

This piece combines projection with materials to evoke an understanding of a storm. How is a storm felt rather than described?

-

(but a storm is blowing in from Paradise)

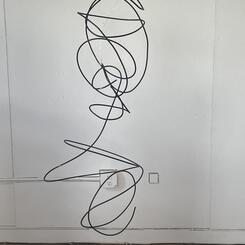

(but a storm is blowing in from Paradise)This piece is made from two 12' lengths of rolled copper wire, which were joined together, spray painted, and suspended from the ceiling. The shapes on the wall behind are its own shadow and a projection of another scribbled wire form. The shape on the floor is cut from 2" thick rubber.

-

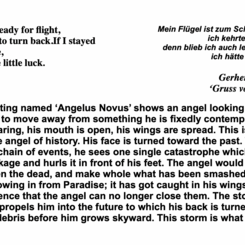

Walter Benjamin, On the Concept of History

Walter Benjamin, On the Concept of HistoryThe image Benjamin conjured, published in 1940, has been something I've been unable to shake. Our inability to turn away from trauma, to move past events, causes further destruction on a personal and socio-historical level. How do we turn? Is turning a form of survival?

-

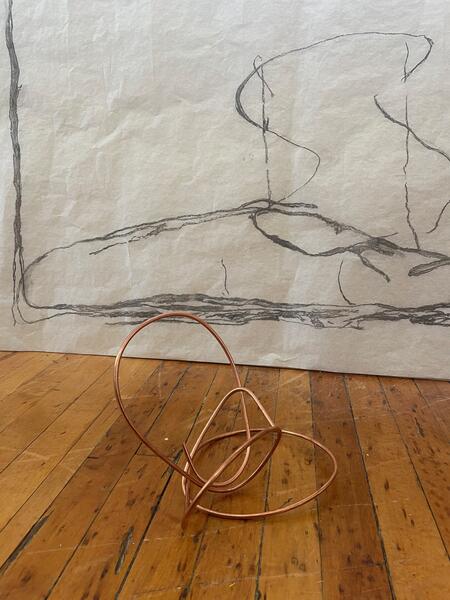

Being satisfied with the line

Being satisfied with the lineI think Benjamin's storm must be felt before we can move past it. This charcoal drawing, one of a series investigating different perspective views on the horizon, came out of me very quickly. I loved it, but as charcoal on trace paper, I knew it wasn't "finished". I tried bending copper to try to capture the speed of the lines.

-

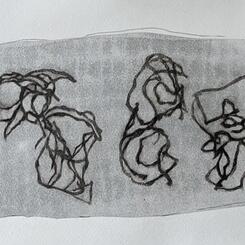

Printmaking: The Rock Eaters

Printmaking: The Rock EatersWhile I waited for a solution, the storm kept popping up any time I moved my hand. Here it became an etching; what I think of as a family portrait, three figures bound in grief.

-

Life size figure

Life size figureSomething about the identification of the storm with the figure allowed me to trust the lines and make this sculpture. This is 24' of 1/4" copper wire spray painted black and suspended from the ceiling. I bent it by laying it on the ground and wrapped, pushed, and pulled using a shipping tube for resistance. It was an intensely physical process that challenged ideas of "storm" and articulated them into rage and grief. Now a figure? Now a storm? You meet it at eye level.

The Catch Table and Fishing Lamp

The Catch Table and Fishing Lamp are the first pieces made for a collaboration with Koba Furniture, ARROWSPACE X KOBA. The shapes used in these designs were generated from a pattern making process used for garments, and then explored through a material lens afforded by my experience with jewelry making.

Testing an idea that objects are frozen moments in time, I hoped to create a sense of dynamism. In design contexts, it asks the client to participate: the forms that make up the base of the table can be arranged in a few different ways, and the wood details on the top are movable even after installation.

(Photo by Amy Boone-McCreesh)

-

The Catch Table and Fishing LampAvailable for Purchase

The Catch Table and Fishing LampAvailable for Purchasehttps://www.kobafurniture.com/products/arrowspace-x-koba?variant=46871663706356

-

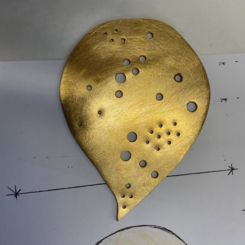

Shapes inspired by jewelry making practices

Shapes inspired by jewelry making practicesUsing the same shapes I generated from garment design, I started to ask what they might do at larger scales, in various combinations, in different materials. I love cutting, drilling, and sanding metal. Something about the tactile nature of metal suggested furniture.

-

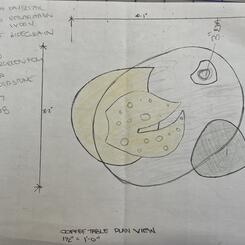

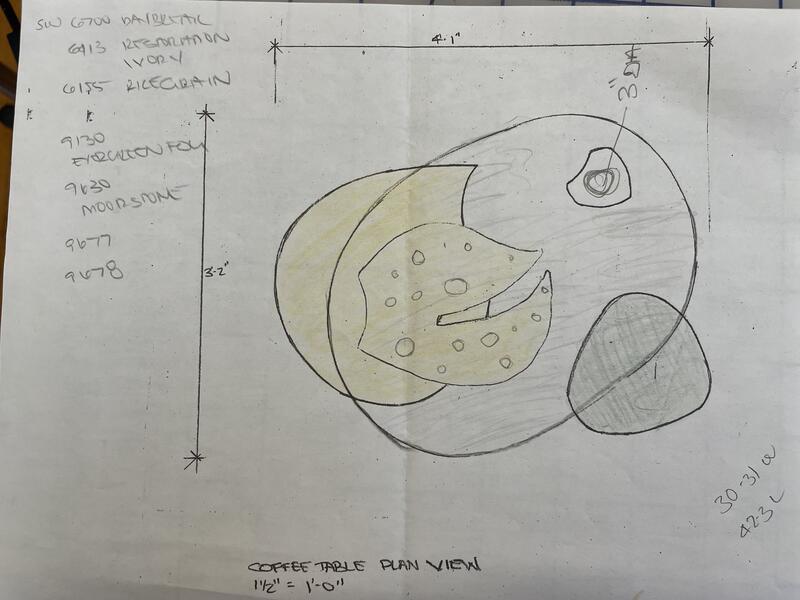

Working drawings

Working drawingsWorking in conversation with Sam Acuff at Koba Furniture, we discuss cost, material, and shipping constraints, as well as construction details. The drawings are made over and over again until it is time to prototype.

-

Prototypes ready to go

Prototypes ready to goAfter a few rounds of prototyping, it's all ready to show.

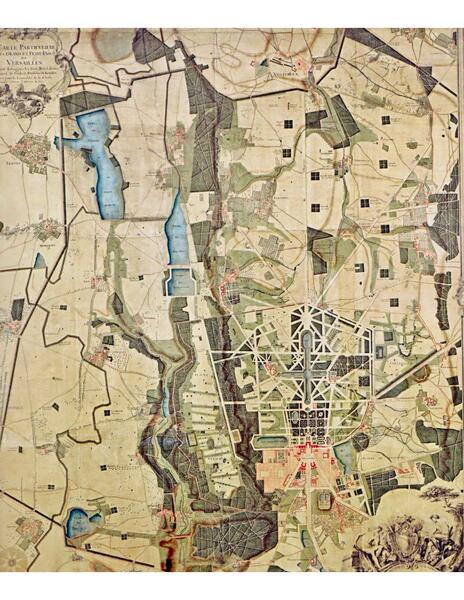

A Dime A Dozen

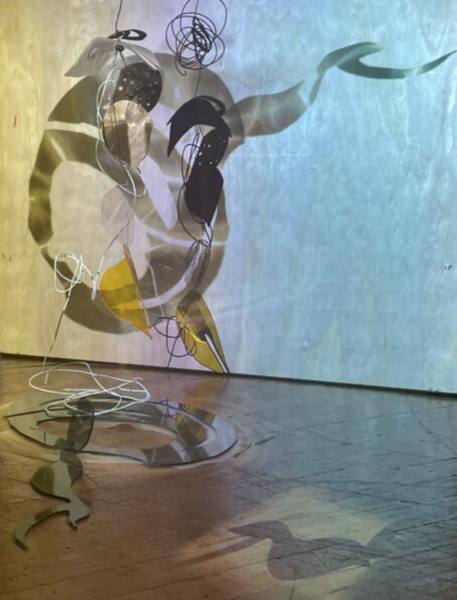

As I combine my shapes into various compositions, a narrative about landscape is emerging. Here I imagined fishing in a murky pond; that moment when you catch something and you are unsure if it's a boot, or a fish, or a piece of trash. You won't know until you name it.

I worked with Dave Greber, who helped me capture my shapes in a projection mapping software. We presented them in such a way as to cast doubt on material reality. The shadows, the reflected light, and the movement all work to remind the viewer that they don't ever quite know what is real.

-

A Dime A Dozen

A Dime A Dozen -

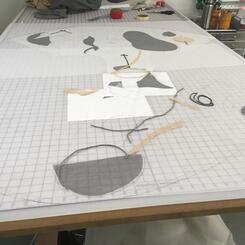

Shapes waiting for a composition

Shapes waiting for a compositionMy studio is full of shapes cut from different materials, waiting to be applied to different circumstances. The constraint of variable contexts helps me determine what they might mean. I think of these as the piercing of water, a tumor, a mouth.

-

Shapes

ShapesThis is another shape that reappears in my work. Here it floats on the surface of the "water" sugesting what kind of environment we're dwelling in. A watery hunting image.

-

In progress: observation of shadows

In progress: observation of shadowsI built the sculpture on the body, as an object to be held. While documenting the process, I realized that the shadows were as much a part of what was being conceptually "held" as the concrete objects were. I realized then that I would need projection mapping in order to finish it.