Work samples

-

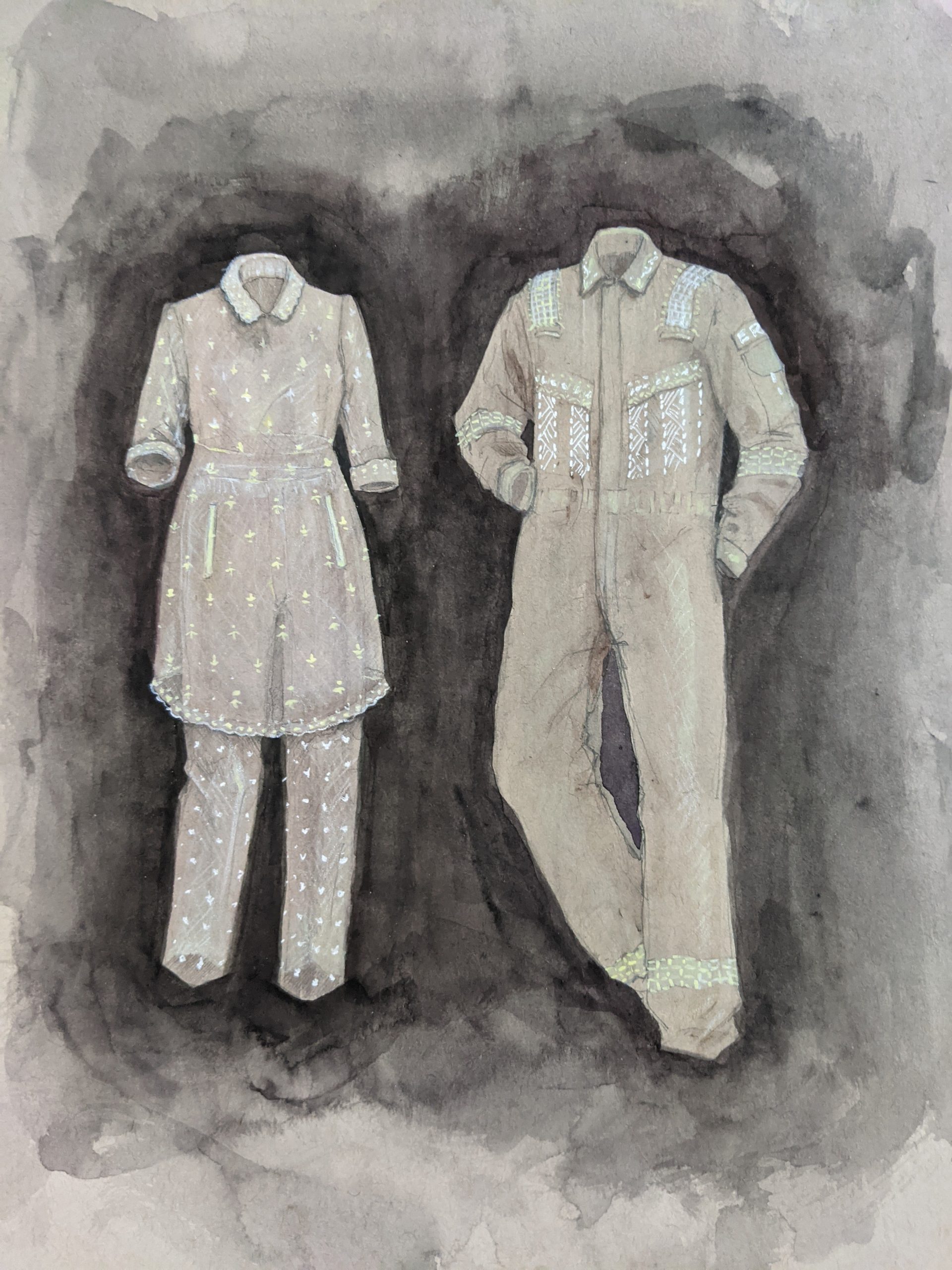

Export Quality (Value Studies: Uniforms)

Export Quality (Value Studies: Uniforms)2023

Machine embroidered piña cloth, white sand, sugar, pearls, and human teethAvailable for PurchaseFor preview or sales inquiries, please contact Wil Aballe, [email protected]

-

My Filipino Baby (Value Studies Series)

My Filipino Baby (Value Studies Series)Detail of last broom of four.

2023

Human hair, plastic rattan, wood, and wire"The text on the broom handles read as follows:

"She’s my darling Filipino Baby

She’s my treasure and my pet

Her teeth are bright and pearly

And her hair is black as jet"- Chorus from "Ma Filipino Babe (1898)" by Charles Kassell Harris

Available for PurchaseFor preview or sales inquiries, please contact Wil Aballe, [email protected]

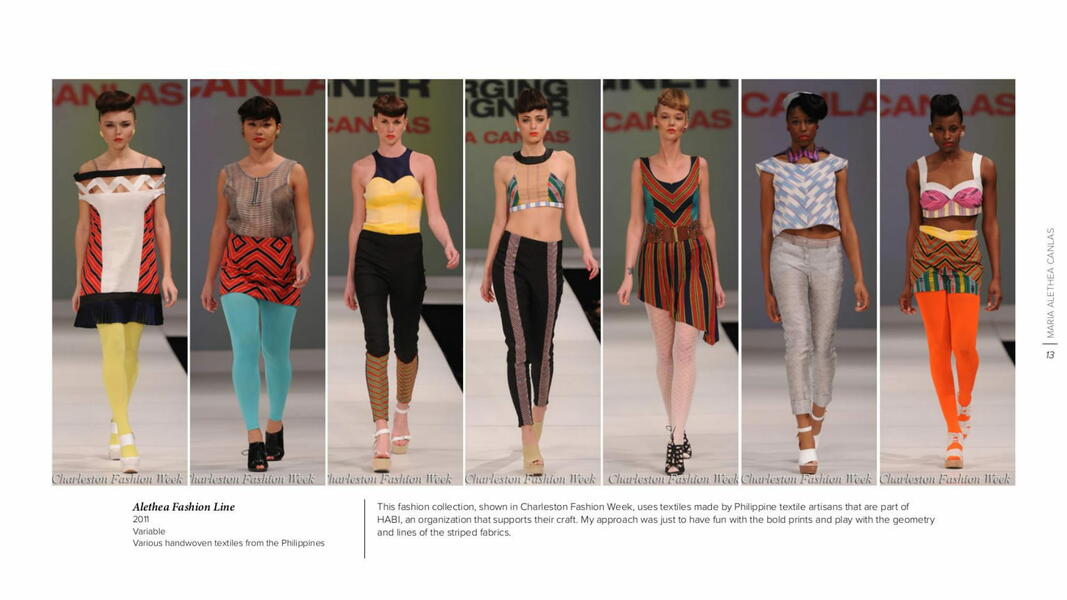

About Thea

Thea Canlas is a Filipina-American artist whose conceptual, research-driven work explores the entanglements of diasporic Philippine identity through sculptural objects, installations, and digital media. Her current body of work, Value Studies, traces how colonial economies and contemporary racial capitalism… more

Flag Studies (In Progress)

Flag Studies is a meditation on statecraft and how Philippine national identity is invented and imagined. This series also aims to critique the state-sanctioned "imaginings" of Philippine national identity, its ties to American imperial rule, and how its contemporary articulations evolve within the Philippine diaspora. For these studies, I use different types of fabric from all over the Philippines, along with imagery from various sources. The material histories of the textiles are again significant in conveying the complexity and overlaps within national identity and histories of commodification. The use of woven textiles from various parts of the Philippines is both a way to try to represent the myriad of indigenous communities largely unseen and show how the textiles have morphed for tourist consumption. Each flag speaks as a gesture or tangent, the collective expression fluctuates over time as new flags are added or reworked.

-

Flag Studies Installation #1

Flag Studies Installation #1Flag Studies Installation #1. 2023.

Machine embroidered piña cloth, traditional textiles from different parts of the Philippines, and digitally printed polyester satin.Emily Carr University of Art and Design, Vancouver, B.C., Canada.

-

Flag Studies Installation #2

Flag Studies Installation #2 -

Flag Studies Installation #3

Flag Studies Installation #3 -

Flag Studies Installation #3 (Detail)

Flag Studies Installation #3 (Detail) -

Installation view of "Flag Studies (Value Studies Series)"

Installation view of "Flag Studies (Value Studies Series)" -

Flag Studies Installation #3 (Detail View)

Flag Studies Installation #3 (Detail View)

"Wish You Were Her" Series

In the Philippines, the term "Export Quality" denotes that a product is produced with more care and better ingredients simply because it's created for a foreign consumer. It is often woven into the handles of colorful decorative versions of tiger grass brooms known as "walis tambo", created for tourist shops all over the Philippines. This piece is a meditation on Philippine feminine identity in the Western imagination and its entanglements with exploited gendered labor and exoticized desire. I recreated the walis tambo and exchanged the bristles with long black human hair, imitating the look and style of hair associated with essentialized Asian feminine identity in the west.

Also shown is a photo series called "Wish You Were Her" wherein the broom is photographed in different landmarks around Washington, DC.

-

Detail view of My Filipino Baby

Detail view of My Filipino Baby -

Export Quality

Export Quality"Export Quality", 2022. Hair, plastic rattan, and bamboo.

-

Wish You Were Her (National Gallery II: empty gallery in Contemporary wing)"Wish You Were Her (National Gallery II: empty gallery in Contemporary wing)", 2022. Digital photograph. "Wish You Were Her" is a photo series wherein the walis tambo (broom) is photographed in different landmarks around Washington, DC. For this series, I was interested in picking specific sites that were predominantly aesthetically white, or made of white marble for the broom to sit in. These were also spaces that denote class and power.

Wish You Were Her (National Gallery II: empty gallery in Contemporary wing)"Wish You Were Her (National Gallery II: empty gallery in Contemporary wing)", 2022. Digital photograph. "Wish You Were Her" is a photo series wherein the walis tambo (broom) is photographed in different landmarks around Washington, DC. For this series, I was interested in picking specific sites that were predominantly aesthetically white, or made of white marble for the broom to sit in. These were also spaces that denote class and power. -

"Wish You Were Her (Federal Trade Commission)", 2022. Digital photograph."Wish You Were Her (Federal Trade Commission)", 2022. Digital photograph. "Wish You Were Her" is a photo series wherein the walis tambo (broom) is photographed in different landmarks around Washington, DC. For this series, I was interested in picking specific sites that were predominantly aesthetically white, or made of white marble for the broom to sit in. These were also spaces that denote class and power.

"Wish You Were Her (Federal Trade Commission)", 2022. Digital photograph."Wish You Were Her (Federal Trade Commission)", 2022. Digital photograph. "Wish You Were Her" is a photo series wherein the walis tambo (broom) is photographed in different landmarks around Washington, DC. For this series, I was interested in picking specific sites that were predominantly aesthetically white, or made of white marble for the broom to sit in. These were also spaces that denote class and power. -

My Filipino Baby (Value Studies Series) Installation #2

My Filipino Baby (Value Studies Series) Installation #22025

Human hair, plastic rattan, wood.

-

My Filipino Baby (Value Studies Series) Detail View

My Filipino Baby (Value Studies Series) Detail View2025

Still Life: Longing (Work in progress)

2022

Commercial refrigerator containing goods purchased at Baltimore H-Mart (rambutan, bangus, green papaya, jackfruit, can of corned beef, can of Tocino Spam, banana heart, mangoes, calabaza, eggplants, sugar canes, ampalaya, and banana leaves)

In "Still Life: Longing", I wanted to create a "still life" informed by the gaze of displacement and longing. I also wanted to emphasize how early colonial economies still inform modern global foodways by mimicking the look of 16th-18th European still lives that featured products from colonies and were prized for their exotic nature, novelty, and rarity. Presenting it as an installation within a commercial refrigerator was key to recalling modern industrial mechanisms of global commerce and exchange. The selection of objects are also significant--I wanted to collect from whichever city I am in (in this case, Baltimore) and buy what I can from what is locally available. I specifically chose fruits, vegetables, and other goods that speak to what I miss from the Philippines. The selection also represents the extent of availability of Philippine goods within a certain area. Some goods, like the corned beef and Tocino Spam, allude to outside culinary influences and are not Philippine-made but their significance to the community and my ideation of the Philippines is enough to be included. It also recalls historical entanglements with the United States as Spam was introduced to the Philippines in the 1940s when US troops were fighting Japanese forces during World War 2.

-

Mock-up for Installation of "Still Life: Longing"Mock-up for Installation of "Still Life: Longing"

Mock-up for Installation of "Still Life: Longing"Mock-up for Installation of "Still Life: Longing" -

Still Life: Longing (Detail)Still Life: Longing (Detail) 2022 Commercial refrigerator containing goods purchased at Baltimore H-Mart (rambutan, bangus, green papaya, jackfruit, can of corned beef, can of Tocino Spam, banana heart, mangoes, calabaza, eggplants, sugar canes, ampalaya, and banana leaves)

Still Life: Longing (Detail)Still Life: Longing (Detail) 2022 Commercial refrigerator containing goods purchased at Baltimore H-Mart (rambutan, bangus, green papaya, jackfruit, can of corned beef, can of Tocino Spam, banana heart, mangoes, calabaza, eggplants, sugar canes, ampalaya, and banana leaves)

Multo (Apparitions)

The highest proportion of these workers are in domestic service, largely taken on by women, accounting for roughly a quarter of all OFWs. Though the Philippine government hail OFWs as “mga bagong bayani” (new heroes), largely due to their economic contribution to the Philippine economy, these positions are rife with abuse and exploitation. From the International Labor Organization’s report on domestic workers:

"Domestic work is one of the most important sources of employment for Philippine women both in the country and abroad. About one-quarter of Philippine workers deployed overseas every year enter domestic service. Concern for their safety and protection from abuse is particularly strong in the Philippines in the aftermath of the execution of Flor Contemplacion, a Philippine domestic worker in Singapore in 1995. Indeed, the hidden nature of domestic work within the private sphere of the employers’ household and the informal employment arrangements often practiced, make domestic workers particularly vulnerable to exploitation, and in some circumstances, to forced labour and trafficking." (Sayres 2)

Because of the “hidden nature” of domestic work, the abuses of power within these spheres on domestic workers is largely unknown outside of the Philippines.

In Value Studies: Multo (Apparitions), I wanted to highlight the invisibility of this labor force and question how we got to this moment of large-scale exportation of Philippine labor. I researched hours of YouTube content produced by OFWs in domestic service. Several OFWs would film themselves working, illuminating the extent of their labor for others wanting to become OFWs. I was able to gather enough clips of OFWs working in regions with the largest concentrations of OFWs in domestic service to create this series. Using a separate digital camera, I created these “ghostly apparitions” by doing a slow exposure of the Youtube videos.

Value Studies

Value Studies is a series of works in various media that explore the entanglements of global capitalist systems, constructions of cultural identity, and value. I utilize the language of material histories and commodities specifically tied to the collective national identity of the Philippines. I’m also utilizing personal sensorial and material associations in my work, as a way of grounding it in an autoethnographic approach to research and art production. Chromatic value also plays a part in creating these pieces.

-

Mockup for Value Study: My Name is Maria Too (Work in progress)Value Study: My Name is Maria Too 2023 (In progress) Skin whitening soaps in the shape of the Virgin Mary presented on commercial shelving In thinking about the legacy of Spanish colonization in the Philippines, the most deeply felt imprint for me is the imposed impossibility of the feminine ideal informed by the Virgin Mary. I went to an all-girl Catholic school in Manila and a shrine of the Virgin is prominently placed in the center of the school grounds. I would later find out that this is a common architectural feature in many schools all over the Philippines. Maria as a first name was also extremely common for most Filipinas. After moving to the US, I constantly had to explain why my Asian features seem to confuse people when they find out my very Spanish name. In addition to reverence for the Virgin, European beauty standards continue to inform personal worth in the Philippines. Most beauty aisles are well-stocked with skin-whitening soaps and serums; hair bleach, etc.

Mockup for Value Study: My Name is Maria Too (Work in progress)Value Study: My Name is Maria Too 2023 (In progress) Skin whitening soaps in the shape of the Virgin Mary presented on commercial shelving In thinking about the legacy of Spanish colonization in the Philippines, the most deeply felt imprint for me is the imposed impossibility of the feminine ideal informed by the Virgin Mary. I went to an all-girl Catholic school in Manila and a shrine of the Virgin is prominently placed in the center of the school grounds. I would later find out that this is a common architectural feature in many schools all over the Philippines. Maria as a first name was also extremely common for most Filipinas. After moving to the US, I constantly had to explain why my Asian features seem to confuse people when they find out my very Spanish name. In addition to reverence for the Virgin, European beauty standards continue to inform personal worth in the Philippines. Most beauty aisles are well-stocked with skin-whitening soaps and serums; hair bleach, etc. -

Value Study: BalikbayanValue Study: Balikbayan 2022 White sand, pearls, teeth, and air bubble void fill

Value Study: BalikbayanValue Study: Balikbayan 2022 White sand, pearls, teeth, and air bubble void fill -

Value Study: Buhok/BunotValue Study: Buhok/Bunot 2022 Coconut husks, hair, white sand, pearls, and teeth

Value Study: Buhok/BunotValue Study: Buhok/Bunot 2022 Coconut husks, hair, white sand, pearls, and teeth -

Value Study: Coconut (Detail)Value Study: Buhok/Bunot (detail) 2022 Coconut husks, hair, white sand, pearls, and teeth

Value Study: Coconut (Detail)Value Study: Buhok/Bunot (detail) 2022 Coconut husks, hair, white sand, pearls, and teeth -

Value Study: Uniforms (In progress)Value Study: Uniforms. My research into Philippine material culture plays a significant role in finding ways to convey further connections between commodification and identity. For Value Study: Uniforms, I used piña, or pineapple cloth, to play with its rich history within Philippine culture. The pineapple is not native to the Philippines and was brought by the Spanish to grow and export during the colonial period. Piña and embroidered piña became a valuable export for the European market, thus quickly becoming a marker of class within the Philippine colonies. In 1975, after the Philippines gained its independence, President Ferdinand Marcos declared the Barong Tagalog and the Baro’t Saya, two “costumes” made with embroidered piña, as the official “national costumes” of the Philippines. This particular designation was intended to boost the commercial export of these textiles. In Value Study: Uniforms Series (work in progress), I researched the uniforms for the most common occupations OFWs are contracted to do. Domestic helpers, which is considered unskilled labor, accounts for almost a quarter of the work taken on by female-identifying OFWs. Among male-identifying OFWs, [get info]. I then recreated the uniforms completely out of piña, adding traditional embroidery design motifs commonly found on the Barong Tagalog and Baro’t Saya. Most of the embroidery designs are derived from embroidery samples from the 17th-19th century, when current fashions were largely inspired by European and Chines embroidery motifs [Montinola CITE]. I was also interested in how the uniforms differed from each other depending on the country of employment. Piña cloth is a strong diaphanous material making it a versatile medium for material experimentation. Its seeming lightness and sheerness evoke wisps and ghosts—subtle impressions that require closer attention. This quality lends well to physically conveying the invisibility and erasure that I want to allude to with the pieces. For displaying the uniforms, I plan to have the uniforms suspended as if an invisible body is wearing it, using either an acrylic clear dress form or embedding a wire armature into the uniforms.

Value Study: Uniforms (In progress)Value Study: Uniforms. My research into Philippine material culture plays a significant role in finding ways to convey further connections between commodification and identity. For Value Study: Uniforms, I used piña, or pineapple cloth, to play with its rich history within Philippine culture. The pineapple is not native to the Philippines and was brought by the Spanish to grow and export during the colonial period. Piña and embroidered piña became a valuable export for the European market, thus quickly becoming a marker of class within the Philippine colonies. In 1975, after the Philippines gained its independence, President Ferdinand Marcos declared the Barong Tagalog and the Baro’t Saya, two “costumes” made with embroidered piña, as the official “national costumes” of the Philippines. This particular designation was intended to boost the commercial export of these textiles. In Value Study: Uniforms Series (work in progress), I researched the uniforms for the most common occupations OFWs are contracted to do. Domestic helpers, which is considered unskilled labor, accounts for almost a quarter of the work taken on by female-identifying OFWs. Among male-identifying OFWs, [get info]. I then recreated the uniforms completely out of piña, adding traditional embroidery design motifs commonly found on the Barong Tagalog and Baro’t Saya. Most of the embroidery designs are derived from embroidery samples from the 17th-19th century, when current fashions were largely inspired by European and Chines embroidery motifs [Montinola CITE]. I was also interested in how the uniforms differed from each other depending on the country of employment. Piña cloth is a strong diaphanous material making it a versatile medium for material experimentation. Its seeming lightness and sheerness evoke wisps and ghosts—subtle impressions that require closer attention. This quality lends well to physically conveying the invisibility and erasure that I want to allude to with the pieces. For displaying the uniforms, I plan to have the uniforms suspended as if an invisible body is wearing it, using either an acrylic clear dress form or embedding a wire armature into the uniforms.