About DanaidX

Narratives teach us who we are in the world and how to relate to each other. But what happens when the narratives we are taught omit, obscure, or shame the embodied realities we experience? Neurologically humans learn to perceive through categorization. What happens if someone falls between the cracks of communal categories? Our work reaches from those liminal spaces seeking moments of empathetic bridge building and connection.

Although we begin with digital images, we choose to… more

Goddesses, Myths, and Monsters

To become a mother is an act of vulnerability; so too is the process of transition for a trans woman. In the midst of these raw moments loom the cultural myths shaped by idealized womanhood and its contrasting shadow the “monstrous” woman. Misogyny defines women by their ability to bear children as well as elevating their existential capacity for love and care. Many cultures throughout human history have reduced women to three tropes, the maiden, the matron and the hag. The matron, or the idealized mother, ostensibly elevates women to a role that in real life can never be achieved while the purest maiden earns the right to serve as a vessel to become the matron. The monstrous hag is the failed matron. This gives cis women one path to validity and leaves trans women no way to be perceived as legitimate women. For the cis woman who has “achieved” pregnancy and childbirth the weight of idealized motherhood can be crushing. The sainted pedestal is a narrow cliff with sharp rocks of shame lurking below.

For many trans women the process of transition means confronting disgust and rejection on the faces of strangers and loved ones. Simply being themselves conjures the deeply feared monstrous woman, the thing of shame and shadow that tramples on sacred womanhood. Our work wrestles with the way these stories are embedded in our own bodies coloring the way we view ourselves. Perhaps, by playfully depicting the specters that haunt us we can exorcise their presence, clearing space for vulnerability to be a place of human connection.

-

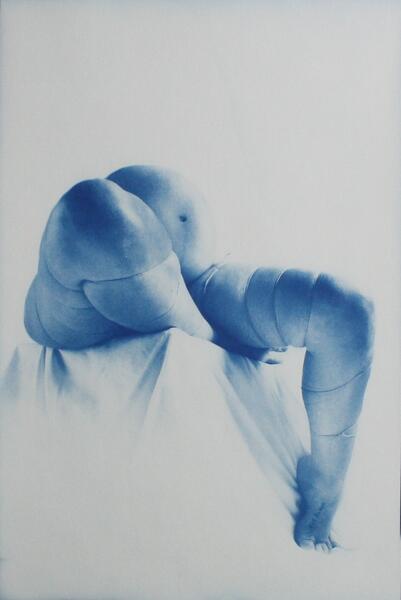

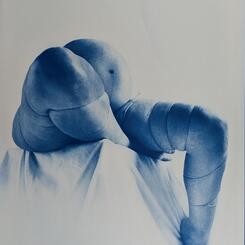

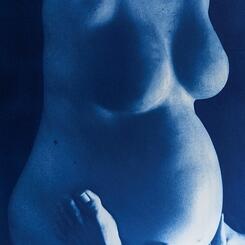

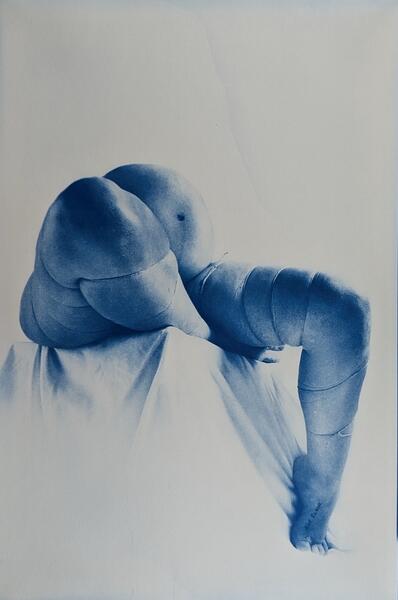

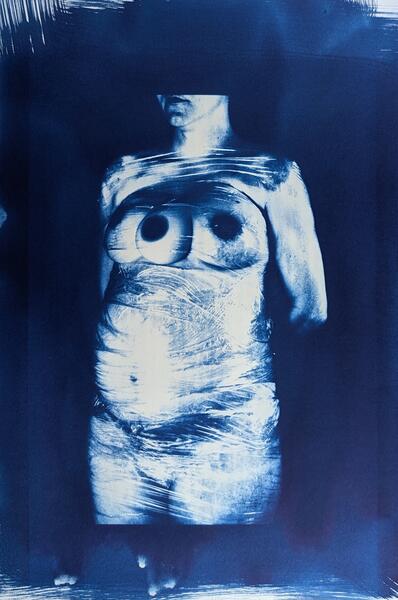

Matron

MatronThe photo shoot for “Matron” took place in the fall of 2023. We wrapped our pregnant model in butcher’s twine. The final proof was not completed until the summer of 2024. Our creative process is one of gestation. It usually takes about nine months from the time of “conception” until the piece has a life of its own. Even though we work in digital photography, our iterative process of finding the image through multiple edits of consecutive negatives and prints is more reminiscent of the lengthy process of drawing or painting than traditional photography. Working in Cyanotype, it is quite difficult to control the final outcome; this leaves room for surprise encounters.

-

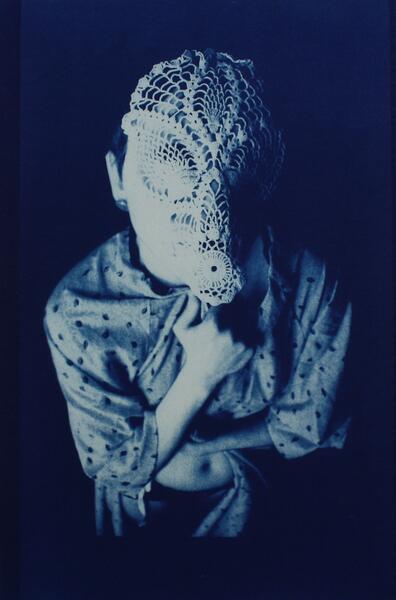

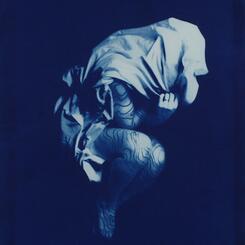

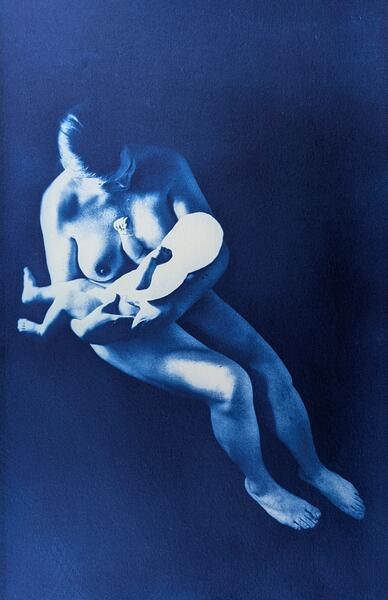

Hypoplasia

HypoplasiaThis piece tries to get at the sense of the lack of the physical aspect of maternity — the inability to nurse or take on the traditional physiological role that a mother has for her baby. The repetition in our printing method reflects the cyclical nature of grief. Longing for what can never be becomes an almost tactile caress of painful imagined images, similar to the Cyanotype process of rhythmically agitating a print in multiple baths. The monochromatic nature Cyanotype lends itself to the melancholy of the yearning ache that this piece reaches for.

-

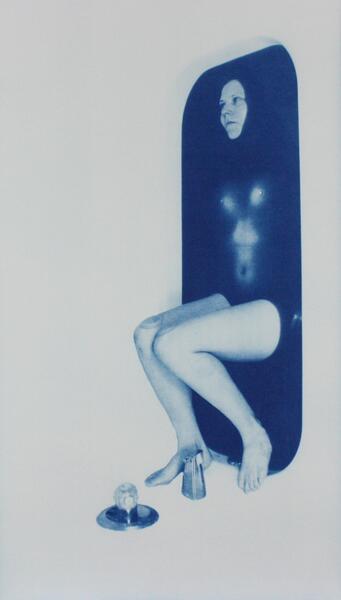

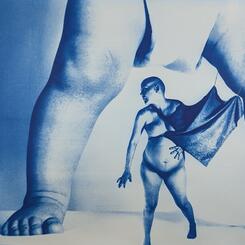

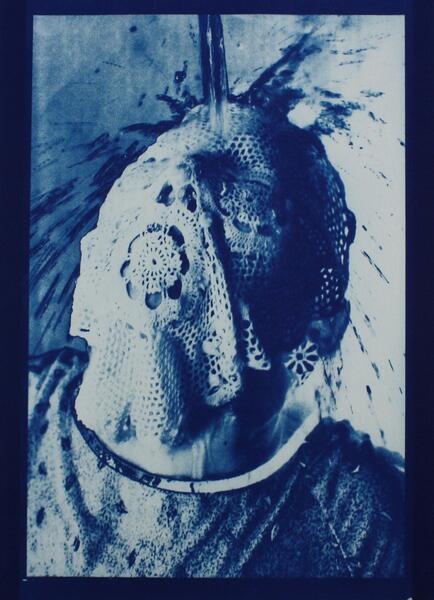

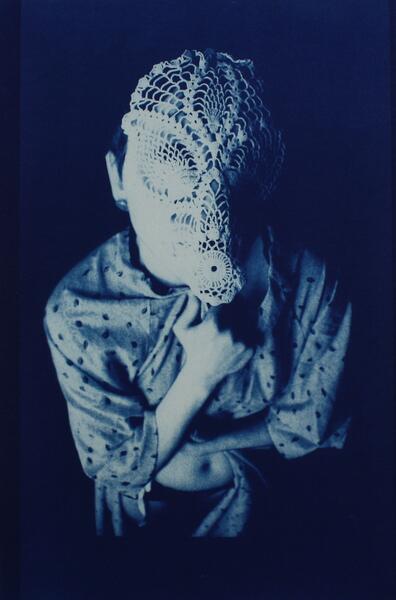

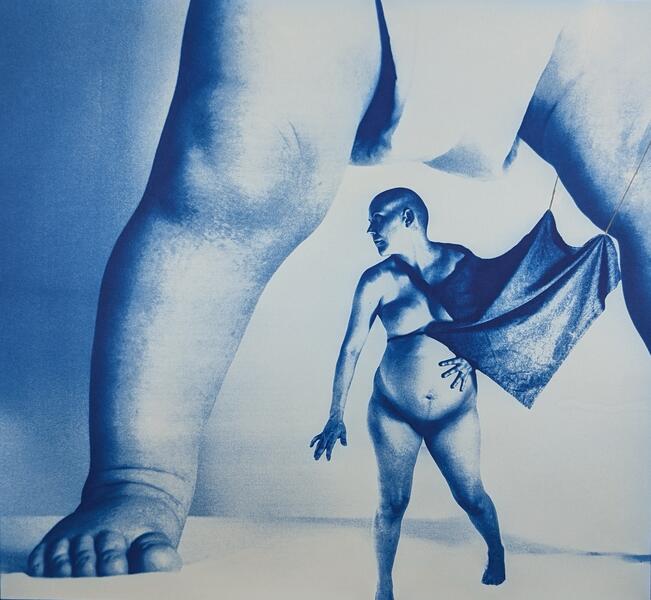

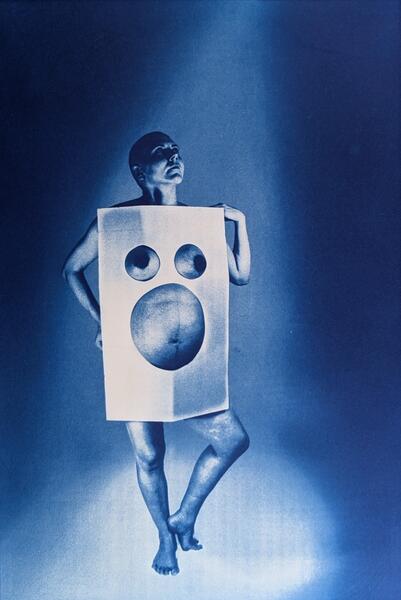

Apron Strings

Apron StringsWe laughed a lot making this piece. It felt like a valid way to dissipate a lot of the fears we have had about being crushed by the cultural construct of motherhood. Although we begin with digital images, we choose to relinquish the control that the digital typically confers by embracing the limitations and variables of the analog cyanotype process. This enables moments of surprise and creative encounter. The choice to see those limitations as enhancing rather than frustrating the creative process challenges the exploitative lens of “overcoming” through which the limits of our bodies and our planet are so often viewed.

-

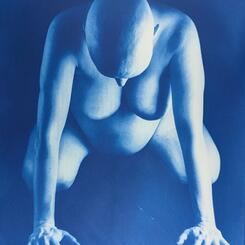

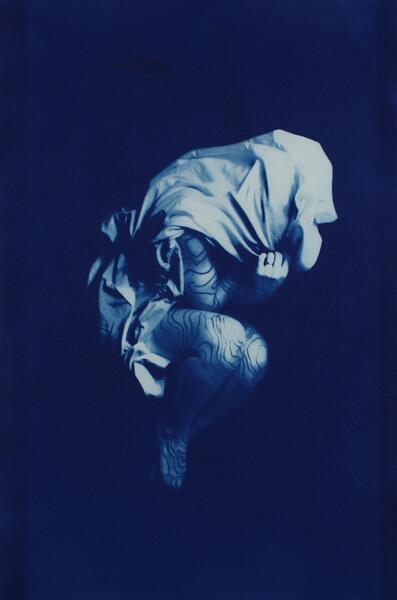

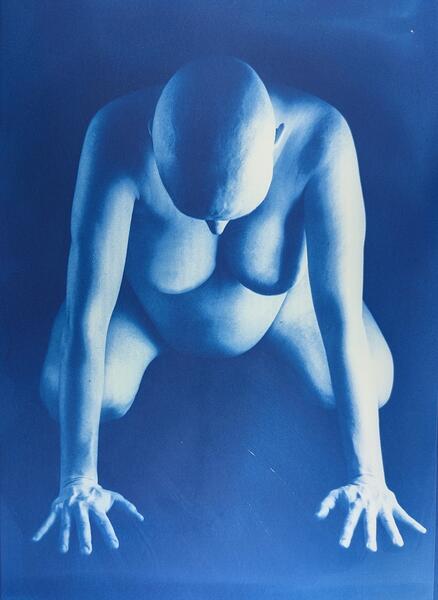

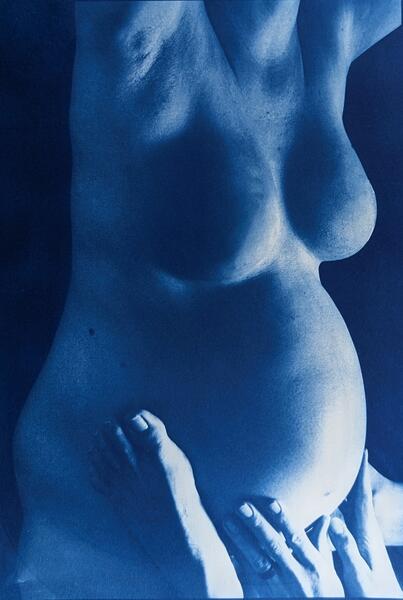

Nucleation Site

Nucleation SiteThis piece evokes a feminist power that embraces the vulnerability of motherhood while rejecting the narrative of fragility. We come to our creative practice from the vantage point of navigating disability and chronic illness. Built into our rhythm of making is the choice to embrace our physical limitations and vulnerabilities and to see them as places for powerful meaning making not as liabilities. Because of this we are often at odds with the frenetic pace of the art world but we have confidence that our slow steady method of honoring our bodies is a place of fruitfulness for both art making and motherhood.

-

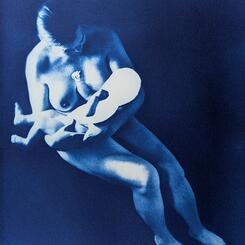

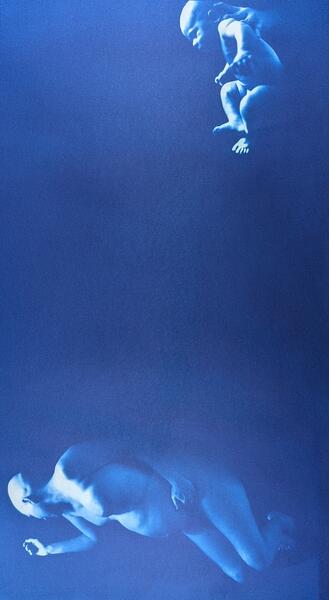

Plangency

PlangencyThis piece has evoked many varied interpretations. It is the first time that we placed two full figures in relation to each other, which brings a new type of tension to the field of blue created in the Cyanotype process. The photoshoot for this image happened during a very vulnerable time for both models and that really comes through. No babies were harmed in the making of this image.

-

Bravo!

Bravo!The reduction of womanhood to the reproductive organs affects all women, cis or trans, straight or gay, those who have given birth and those who have not or cannot. Working with digital photography enables us to explore the human figure without the strain that drawing and painting place upon the artist’s body. We use cyanotype—a 170-year-old non-toxic photographic printing process—because of the visceral physicality of the experience.

-

Placenta #1

Placenta #1The placenta is a large living organ that evolved to be a mediator between the physical needs of two intertwined bodies. Our authoritarian individualistic culture frequently frames questions of human vulnerability in zero sum terms. We see this beautiful bloody organ as a much needed living metaphor for our time. Human limitation does not necessitate a struggle over who’s needs will be prioritized first. Instead, human need and vulnerability are the seeds from which meaning and connection can grow.

-

Placenta #2

Placenta #2The placenta is a large living organ that evolved to be a mediator between the physical needs of two intertwined bodies. Our authoritarian individualistic culture frequently frames questions of human vulnerability in zero sum terms. We see this beautiful bloody organ as a much needed living metaphor for our time. Human limitation does not necessitate a struggle over who’s needs will be prioritized first. Instead, human need and vulnerability are the seeds from which meaning and connection can grow.

-

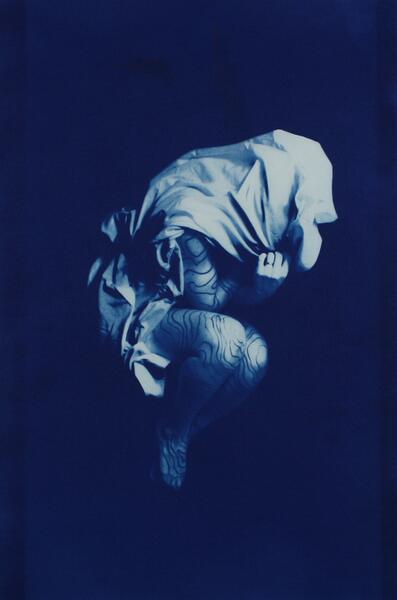

Flaescmangre

FlaescmangreWe originally saw “Theia & The Moon” and “Flaescmangre” as the two sides of the same coin. On one side there is the deification of the idealized woman, the matron, the glowing mother. The direct result of this idealized goddess is the other side of the coin— the lens that reduces women’s personhood to this role butchers their bodies. Women become meat sacrificed to the idealized goddess.

-

Theia & the Moon

Theia & the MoonWe originally saw “Theia & The Moon” and “Flaescmangre” as the two sides of the same coin. On one side there is the deification of the idealized woman, the matron, the glowing mother. The direct result of this idealized goddess is the other side of the coin— the lens that reduces women’s personhood to this role butchers their bodies. Women become meat sacrificed to the idealized goddess.

In the Dark: An Exploration of Chronic Illness

The way we understand each other as human beings is through connecting our own embodied experience with that of someone else. If we do not share a common experience, then cultural narratives and stories enable us to build empathetic bridges to cross that gap. Most people experience pain, exhaustion, and illness as one chapter of their life with a beginning and an end. Disclosure of pain, struggle, or vulnerability are usually met with shame. When faced with physical limitations, we learn that the moral choice is to push through. Not pushing through is unacceptable. There is no familiar non-linear story for those whose bodies struggle in an endless loop of suffering; for those who cannot push through.

In a culture colored by virtuous boot strap pulling, what happens when the body desperately needs rest but cannot sleep, when night after night lying in bed is a place of struggle, failure, and shame? We ask the question, “Is rest a self-indulgent luxury, a sign of moral laziness, or a battleground for human wholeness?”

For many with chronic conditions, routines of self care demand an unyielding repetition. This is reflected in the repetitive rhythms of the way that we approach cyanotype – a 170-year-old non-toxic photographic printing process. For us, the dark blue monochromatic nature of the prints evokes the way that high levels of pain and exhaustion color and dim the senses, disrupting the formation of clear and distinct memories.

Chronic health issues often go hand in hand with trauma, a type of neurological response that occurs when someone feels that their safety is threatened and that they are powerless to change their situation. These experiences are especially common in medical settings where repeated experiences of being unheard can be traumatic even if doctors are good doctors and intend no harm.

When confronted with other people’s pain, the instinct is to remove that discomfort by either looking away, or trying to fix it. In sharing this work we are asking the viewer to enter uncomfortable spaces with a different posture. The vulnerability of these images is an invitation to join in that vulnerability through the work of stretching the imagination beyond pity, beyond judgment, beyond fear.