About Lynne

Lynne Parks was born and raised in Northern Virginia. She has been a resident of Baltimore, MD since 2003. She has a BA from Hollins University with an independent major in creative writing/theater/film studies. She is the Outreach Coordinator for Lights Out Baltimore, a bird conservation and wildlife rescue organization.

She is a practicing visual artist, curator, writer, and performer.

She is a practicing visual artist, curator, writer, and performer.

Jump to a project:

Writings--essay, dramatic monologue, short fiction

I focused on writing in 2018, including essays, monologues, and short fiction. I attended the Kenyon Writer's Workshop and was published in The Dalhousie Review. I'm currently working on a book of essays and a play comprised of six monologues.

Missing Birds, Birdland and the Anthropocene

Birdland and the Anthropocene opened at The Peale Center in October of 2017 and ran for a month. It is an exhibit I curated and participated in as an artist. Missing Birds was my mixed media work that was included in the show. I also performed in an extinction ritual choreographed by Jess Rassp. Additionally, I hosted workshops with the Baltimore Lab School and Make Studio. The resulting work was included in the exhibit.

https://www.google.com/culturalinstitute/beta/exhibit/mAIimZw87IYdLA

https://www.google.com/culturalinstitute/beta/exhibit/mAIimZw87IYdLA

-

missing birds in Birdland and the Anthropocene

missing birds in Birdland and the Anthropocene -

missing birdsPart of the Birdland and the Anthropocene exhibit at The Peale Center.

missing birdsPart of the Birdland and the Anthropocene exhibit at The Peale Center. -

missing birds, spotted sandpiper

missing birds, spotted sandpiper -

missing birds, lazuli bunting

missing birds, lazuli bunting -

missing birds, green kingfisher

missing birds, green kingfisher -

Missing Birds

Missing Birds -

Extinction Ritual, Mountain QuailIn addition to the inclusion of visual and sound work in Birdland and the Anthropocene, I initiated an extinction ritual. Jess Rassp choreographed the piece and designed the costumes. I performed as a Mountain Quail.

Extinction Ritual, Mountain QuailIn addition to the inclusion of visual and sound work in Birdland and the Anthropocene, I initiated an extinction ritual. Jess Rassp choreographed the piece and designed the costumes. I performed as a Mountain Quail. -

Extinction Ritual, Birdland and the Anthropocene

Extinction Ritual, Birdland and the Anthropocene -

workshops.jpgThis shows work from workshop participants from the Baltimore Lab School and Make Studio.

workshops.jpgThis shows work from workshop participants from the Baltimore Lab School and Make Studio. -

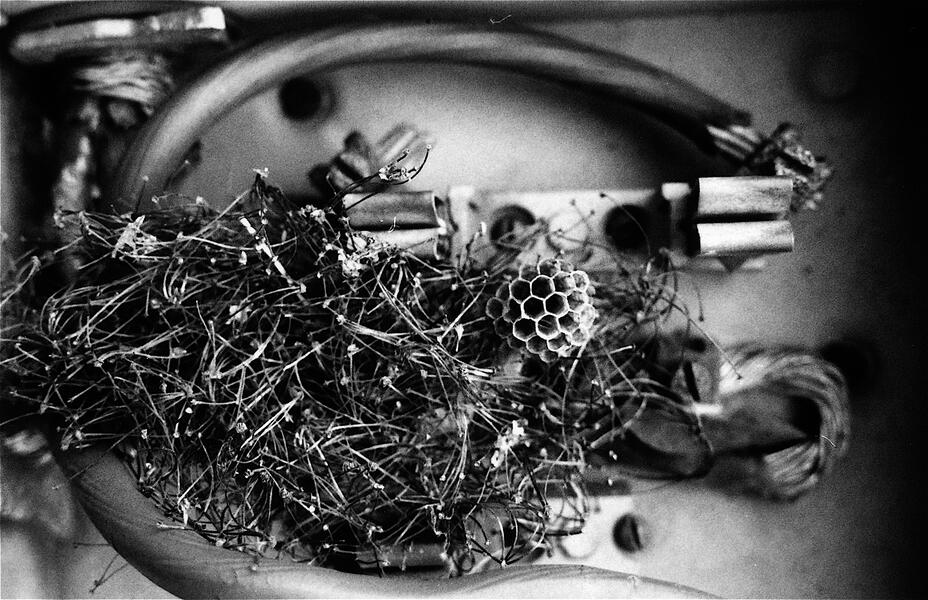

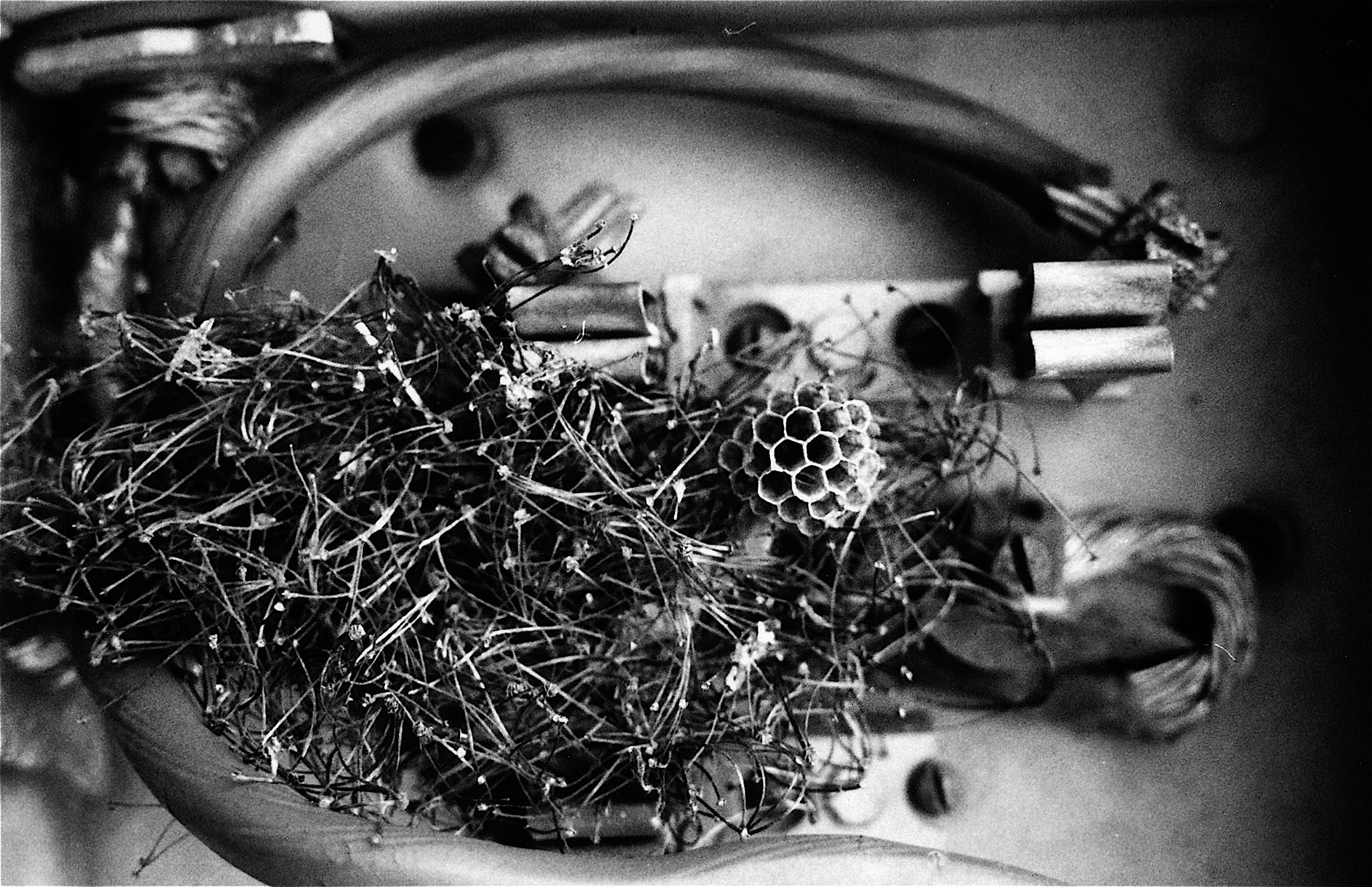

Gray Catbird nest, Birdland and the AnthropoceneIncluded in the curation of thirty artists in Birdland and the Anthropocene, I collected and placed a number of found objects that illustrate the Anthropocene. This catbird nest weaves together vines, the ribbon from a balloon, a swiffer, and bits of plastic bags. It shows how much humans have changed the natural world and its processes.

Gray Catbird nest, Birdland and the AnthropoceneIncluded in the curation of thirty artists in Birdland and the Anthropocene, I collected and placed a number of found objects that illustrate the Anthropocene. This catbird nest weaves together vines, the ribbon from a balloon, a swiffer, and bits of plastic bags. It shows how much humans have changed the natural world and its processes.

Lights Out Baltimore

In 2009, I began volunteering with Lights Out Baltimore (LOB), a bird conservation/citizen science/wildlife rescue organization. LOB seeks to make Baltimore safe for migratory birds by encouraging downtown buildings to turn off nonessential lighting during migration. Volunteers monitor collisions in the city during the spring and fall collecting fatalities and logging strike data--date/location/species--as well as transporting injured birds to a wildlife rehabilitator. The dead birds are donated to the Smithsonian Natural History Museum to be used for research or museum specimens.

Since 2010, I have taken photographs of several of the fatalities we've collected. I think of them as portraits honoring the loss of individuals and this intention has been influenced by memorial photography.

As many as a billion birds are dying annually in the United States from building collisions. Songbirds and shorebirds that migrate at night to avoid predators navigate by the moon and starlight, as well as the earth's magnetic field.

Disorienting light pollution, bright white and yellow light, attracts birds into urban environments where they encounter a maze of invisible barriers, glass. Birds perceive the world differently than we do. Windows either show what appears to be a clear pathway or a reflective surface that looks real. Only by breaking up large panes of glass with designs that follow a 2" horizontally or 4" vertically oriented rule, can we achieve bird-friendly glass. It's generally the first thirty feet from the ground upward that is problematic.

I hope to inspire bird-friendly building design.

Since 2010, I have taken photographs of several of the fatalities we've collected. I think of them as portraits honoring the loss of individuals and this intention has been influenced by memorial photography.

As many as a billion birds are dying annually in the United States from building collisions. Songbirds and shorebirds that migrate at night to avoid predators navigate by the moon and starlight, as well as the earth's magnetic field.

Disorienting light pollution, bright white and yellow light, attracts birds into urban environments where they encounter a maze of invisible barriers, glass. Birds perceive the world differently than we do. Windows either show what appears to be a clear pathway or a reflective surface that looks real. Only by breaking up large panes of glass with designs that follow a 2" horizontally or 4" vertically oriented rule, can we achieve bird-friendly glass. It's generally the first thirty feet from the ground upward that is problematic.

I hope to inspire bird-friendly building design.

-

Death by Glass, Black-throated Blue Warbler

Death by Glass, Black-throated Blue Warbler -

Death by Glass, Worm-eating Warbler

Death by Glass, Worm-eating Warbler -

Common Yellowthroats

-

Gray Catbird

-

Rose-breasted Grosbeak

Rose-breasted Grosbeak -

Wood Thrush

Wood Thrush -

Blackpoll Warbler

Blackpoll Warbler -

American Redstart

American Redstart -

Barn Swallow

Barn Swallow -

Bird-B-Gone: Extinction Countdown installation, Flight Risk, solo show, Sandbox Initiative, Washington CollegeI contrasted the predator eye bird strike deterrence product, Bird-B-Gone, with Sibley's Backyard Birding Postcards to create this wall installation in conjunction with my glass environment photographs. The tear shaped "eyes" created bird-shaped reflections on the wall.

Bird-B-Gone: Extinction Countdown installation, Flight Risk, solo show, Sandbox Initiative, Washington CollegeI contrasted the predator eye bird strike deterrence product, Bird-B-Gone, with Sibley's Backyard Birding Postcards to create this wall installation in conjunction with my glass environment photographs. The tear shaped "eyes" created bird-shaped reflections on the wall.

Bird/Glass Collision solutions 2015-2017

Lights Out Baltimore (cont.) bird/glass collision awareness

In the past three years, I continued my study of birds and building collisions. I had solo art shows and curated art shows that addressed the bird/glass collision issue. I gave talks at campuses, galleries, a bird conservation conference, women's groups, and bird clubs. I realized I wanted to push forward with the project and find solutions. I began incorporating bird-safe window film cut-outs in my shows. That led to invitations to treat windows at a national wildlife refuge visitor center, an elementary school, and a wildlife rehabilitation center. A 4th grade Lego League team championed the cause and with my mentorship won a regional competition and is taking the project to state. Here are some of the windows I treated as well as new window film designs. The 2"x4" rule has been implemented. Birds will not fly in between spaces that are 2" or less horizontally oriented or 4" or less vertically oriented.

Also included here are some of the glass environments we find birds in during our monitoring of downtown Baltimore during spring and fall migration.

In the past three years, I continued my study of birds and building collisions. I had solo art shows and curated art shows that addressed the bird/glass collision issue. I gave talks at campuses, galleries, a bird conservation conference, women's groups, and bird clubs. I realized I wanted to push forward with the project and find solutions. I began incorporating bird-safe window film cut-outs in my shows. That led to invitations to treat windows at a national wildlife refuge visitor center, an elementary school, and a wildlife rehabilitation center. A 4th grade Lego League team championed the cause and with my mentorship won a regional competition and is taking the project to state. Here are some of the windows I treated as well as new window film designs. The 2"x4" rule has been implemented. Birds will not fly in between spaces that are 2" or less horizontally oriented or 4" or less vertically oriented.

Also included here are some of the glass environments we find birds in during our monitoring of downtown Baltimore during spring and fall migration.

-

Patuxent Wildlife Research Center, bird-friendly window film designYou can still see some of the reflective glass on the outside of the visitor center at the Patuxent Wildlife Research Center. I designed these patterns for the bird-friendly window film that has been applied to four of the large panes. The is the outside surface of the glass.

Patuxent Wildlife Research Center, bird-friendly window film designYou can still see some of the reflective glass on the outside of the visitor center at the Patuxent Wildlife Research Center. I designed these patterns for the bird-friendly window film that has been applied to four of the large panes. The is the outside surface of the glass. -

Patuxent Wildlife Research Center, bird-friendly window filmThese are the large reflective front windows at the visitor center at the Patuxent Wildlife Research Center that have been treated with bird-friendly window film. This is the view from inside looking out. You still get a view.

Patuxent Wildlife Research Center, bird-friendly window filmThese are the large reflective front windows at the visitor center at the Patuxent Wildlife Research Center that have been treated with bird-friendly window film. This is the view from inside looking out. You still get a view. -

IMG_2649.jpgI designed four patterns of bird-friendly window film design to be applied to the front windows at the Visitor Center of the Patuxent Wildlife Research Center. This is a wall paper effect using a perforated window film applied on the outside surface of the glass to break up deadly reflections. The pattern also illustrates the 2x4 rule. Birds will not attempt to fly in between a pattern that is four inches or less when vertically oriented, or two inches or less when horizontally oriented. Each shape was hand drawn, scanned, and vectored.

IMG_2649.jpgI designed four patterns of bird-friendly window film design to be applied to the front windows at the Visitor Center of the Patuxent Wildlife Research Center. This is a wall paper effect using a perforated window film applied on the outside surface of the glass to break up deadly reflections. The pattern also illustrates the 2x4 rule. Birds will not attempt to fly in between a pattern that is four inches or less when vertically oriented, or two inches or less when horizontally oriented. Each shape was hand drawn, scanned, and vectored. -

bird-friendly window film designHere is one panel out of the four bird-friendly window film designs. Each bird is hand drawn, scanned, and vectored. Each design is species-specific.

bird-friendly window film designHere is one panel out of the four bird-friendly window film designs. Each bird is hand drawn, scanned, and vectored. Each design is species-specific. -

bird-friendly window treatmentI conducted two bird-friendly window treatment workshops at the Creative Alliance in 2016. We cut-out shapes from CollidEscape window film utilizing the 2x4 rule.

bird-friendly window treatmentI conducted two bird-friendly window treatment workshops at the Creative Alliance in 2016. We cut-out shapes from CollidEscape window film utilizing the 2x4 rule. -

bird-friendly window designAs part of a Lights Out Baltimore related solo show at the George Washington Carver Center for Arts and Technology, I demonstrated a bird-safe window design treatment employing the 2x4 rule. Birds will not attempt to fly in between a space that is four inches or less when the pattern is vertically oriented, or two inches or less if the pattern is horizontally oriented. I drew the shapes, made templates, and hand cut CollidEscape window film.

bird-friendly window designAs part of a Lights Out Baltimore related solo show at the George Washington Carver Center for Arts and Technology, I demonstrated a bird-safe window design treatment employing the 2x4 rule. Birds will not attempt to fly in between a space that is four inches or less when the pattern is vertically oriented, or two inches or less if the pattern is horizontally oriented. I drew the shapes, made templates, and hand cut CollidEscape window film. -

bird-safe window film treatmentThis is a bird-safe window film treatment I applied at the Fine Arts Gallery, George Mason University as part of the Unfriendly Skies exhibition. Hand drawn shapes, templates, and cut-outs illustrating two bird-safe products--CollidEscape and American Bird Conservancy Bird Tape. The 2x4 rule has been applied.

bird-safe window film treatmentThis is a bird-safe window film treatment I applied at the Fine Arts Gallery, George Mason University as part of the Unfriendly Skies exhibition. Hand drawn shapes, templates, and cut-outs illustrating two bird-safe products--CollidEscape and American Bird Conservancy Bird Tape. The 2x4 rule has been applied. -

bird-safe window treatmentThe interior view from the Fine Arts Gallery, George Mason University as part of the Unfriendly Skies exhibition.

bird-safe window treatmentThe interior view from the Fine Arts Gallery, George Mason University as part of the Unfriendly Skies exhibition. -

bird-safe window treatmentMy first cut-out bird-safe window treatment at a solo show of work on exhibition at The Sandbox Initiative, Flight Risk.

bird-safe window treatmentMy first cut-out bird-safe window treatment at a solo show of work on exhibition at The Sandbox Initiative, Flight Risk. -

bird-safe window treatment, interior viewThe interior view of the bird-safe window installation at The Sandbox Initiative at Washington College. This was part of my solo show, Flight Risk.

bird-safe window treatment, interior viewThe interior view of the bird-safe window installation at The Sandbox Initiative at Washington College. This was part of my solo show, Flight Risk.

the boat that Skip built

Here on the top of a mountain in the Alleghenys sits a boat in a house.

Uncle Olin took us to see the boat. We hopped into his pickup for a slow, steep ride. At this altitude, the trees are thin, but thick with lichen. We startled a wild turkey and a pileated woodpecker. At a declivity a good ways up, we found a high meadow bisected by a stream. Beavers were busy here with lodges and dams. Yellow and chestnut-sided warblers and common yellowthroats sang. A willow flycatcher gave a spirited “fitz-bew” and a yellow-billed cuckoo said “cowp.” Here sat a two-story old farmhouse going to ruin. In the seventies, a “hippie feller” moved in, Skip. He was handy and inventive. Winters were harsh, but local folks took care of him. One day he decided to build a boat in the house. In the house. He made a lathe out of an old chain saw motor held in place by plaster, a bicycle, and other things. He started pulling wood off of the structures at hand including the pig barn. When it was finished, the boat was a thing of beauty. Joinery. No nails, but trenails or dowels. No one knows why he built the boat in the house. He was pulled over in Tennessee and shot when the police thought he was reaching for a gun. There the boat sits in the house, stumbled upon by abandoned house explorers and joy riders. Some inconsiderate soul had spray-painted it; others had stolen bits and pieces from it including the steering wheel. Someone had started pulling the wall out in an attempt to steal it, but there it sits as yet, heavy as hell.

We wind on down the mountain and stop at the general store in Blue Grass. We grab a couple of sandwiches and sit on the front porch. Herman Puffenbarger stops with us. He’s eating powdered sugar donuts. He knew Skip and tells us stories about him. Skip had bought a $3 used lawnmower and attached the motor to his bicycle. He traveled back and forth across the country on it. He traveled to Florida in ten days. He called Herman when he arrived, knowing he would be worried after that trouble in South Carolina. Skip was once arrested for not wearing a helmet and put in jail for a month since he couldn’t pay the fine.

Skip once rigged up a homemade sawmill, but no one else knew how to cut true with it.

Uncle Olin took us to see the boat. We hopped into his pickup for a slow, steep ride. At this altitude, the trees are thin, but thick with lichen. We startled a wild turkey and a pileated woodpecker. At a declivity a good ways up, we found a high meadow bisected by a stream. Beavers were busy here with lodges and dams. Yellow and chestnut-sided warblers and common yellowthroats sang. A willow flycatcher gave a spirited “fitz-bew” and a yellow-billed cuckoo said “cowp.” Here sat a two-story old farmhouse going to ruin. In the seventies, a “hippie feller” moved in, Skip. He was handy and inventive. Winters were harsh, but local folks took care of him. One day he decided to build a boat in the house. In the house. He made a lathe out of an old chain saw motor held in place by plaster, a bicycle, and other things. He started pulling wood off of the structures at hand including the pig barn. When it was finished, the boat was a thing of beauty. Joinery. No nails, but trenails or dowels. No one knows why he built the boat in the house. He was pulled over in Tennessee and shot when the police thought he was reaching for a gun. There the boat sits in the house, stumbled upon by abandoned house explorers and joy riders. Some inconsiderate soul had spray-painted it; others had stolen bits and pieces from it including the steering wheel. Someone had started pulling the wall out in an attempt to steal it, but there it sits as yet, heavy as hell.

We wind on down the mountain and stop at the general store in Blue Grass. We grab a couple of sandwiches and sit on the front porch. Herman Puffenbarger stops with us. He’s eating powdered sugar donuts. He knew Skip and tells us stories about him. Skip had bought a $3 used lawnmower and attached the motor to his bicycle. He traveled back and forth across the country on it. He traveled to Florida in ten days. He called Herman when he arrived, knowing he would be worried after that trouble in South Carolina. Skip was once arrested for not wearing a helmet and put in jail for a month since he couldn’t pay the fine.

Skip once rigged up a homemade sawmill, but no one else knew how to cut true with it.

bound and marked

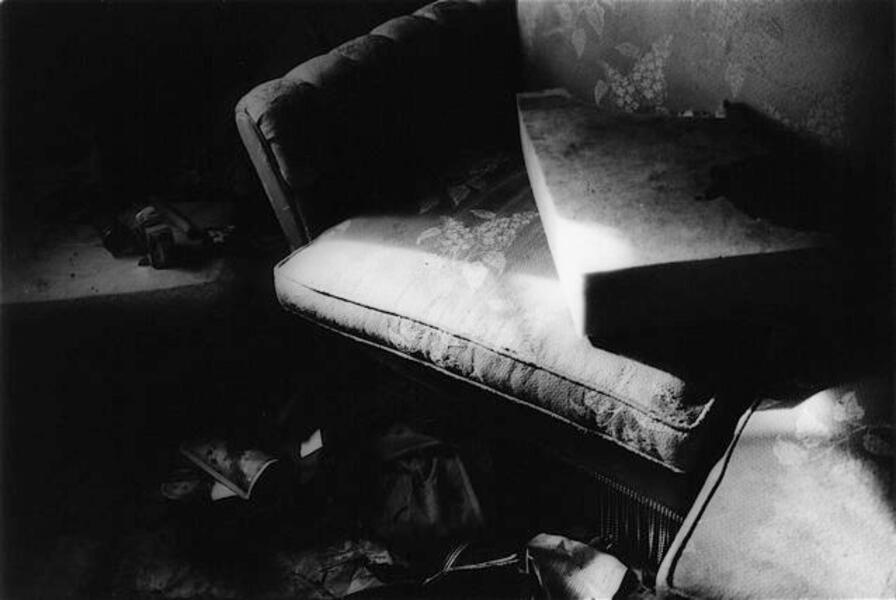

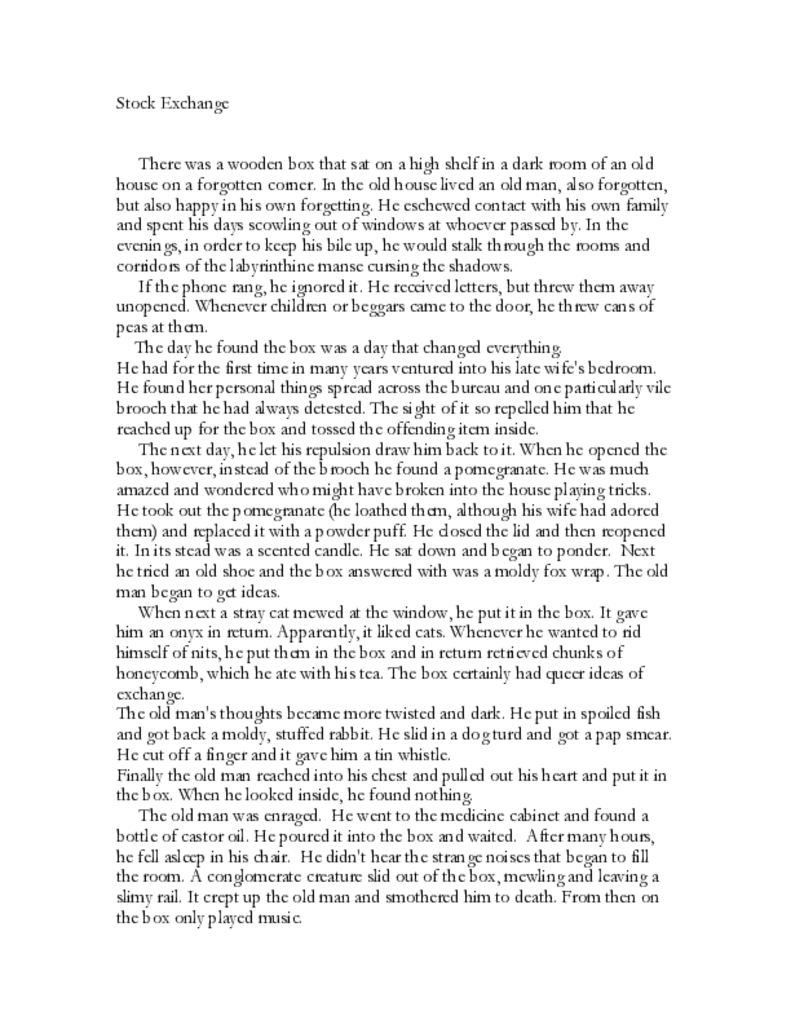

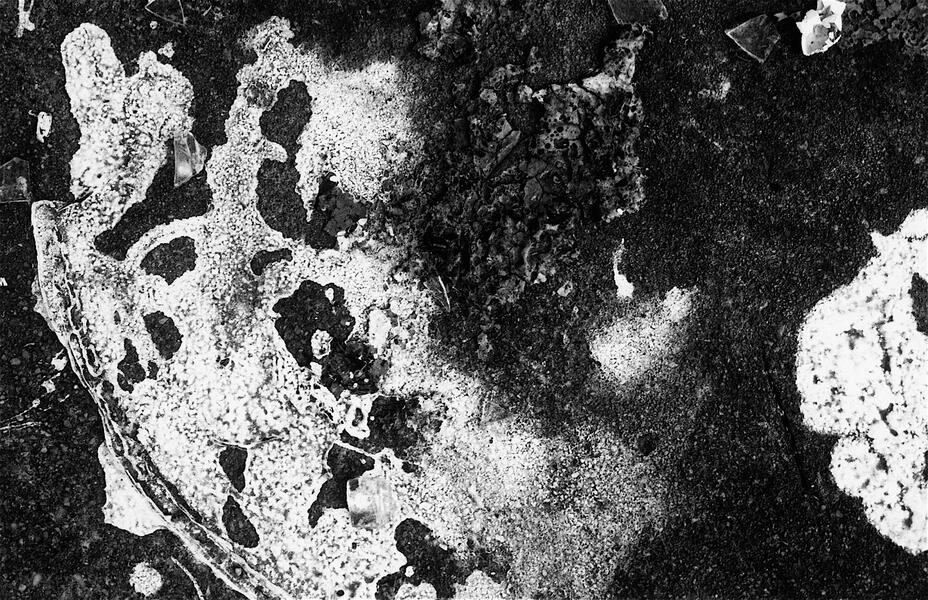

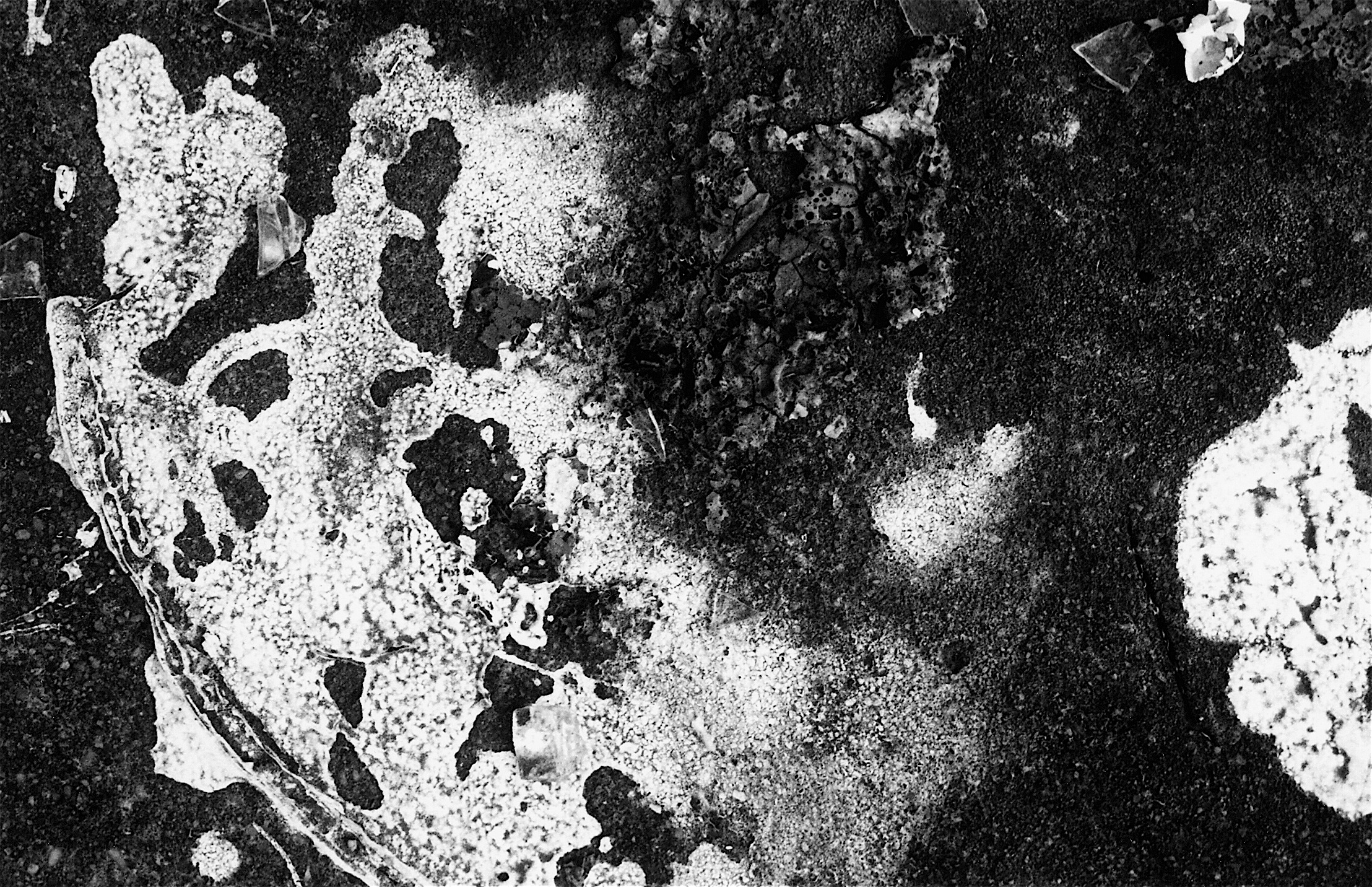

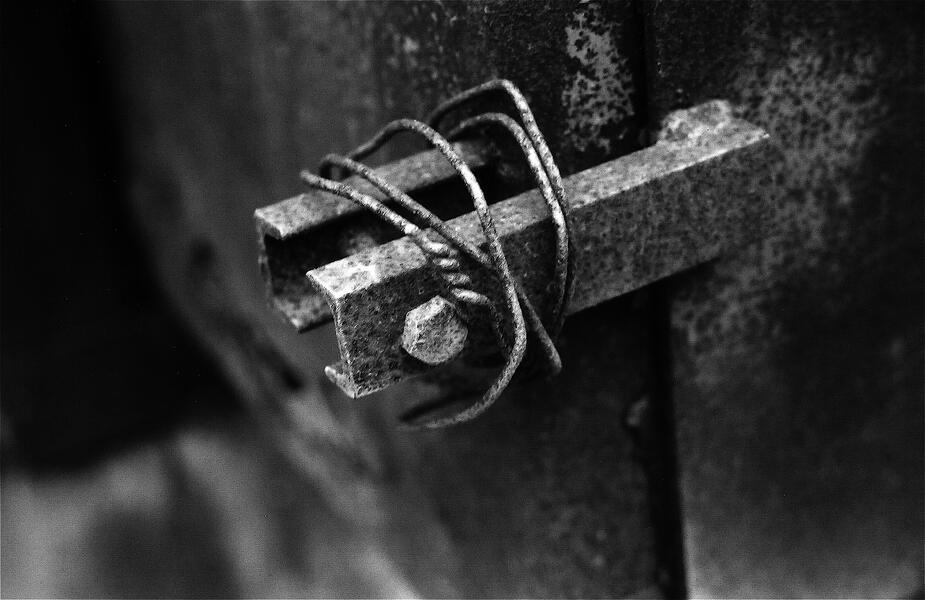

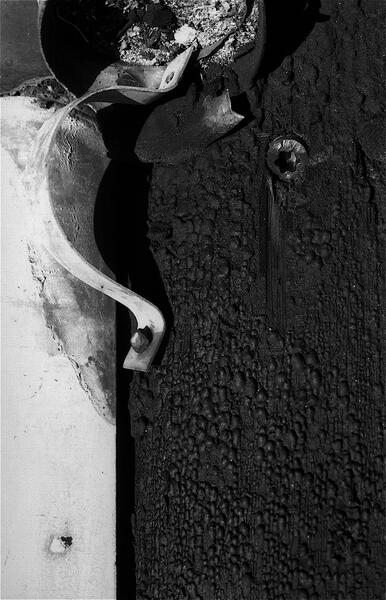

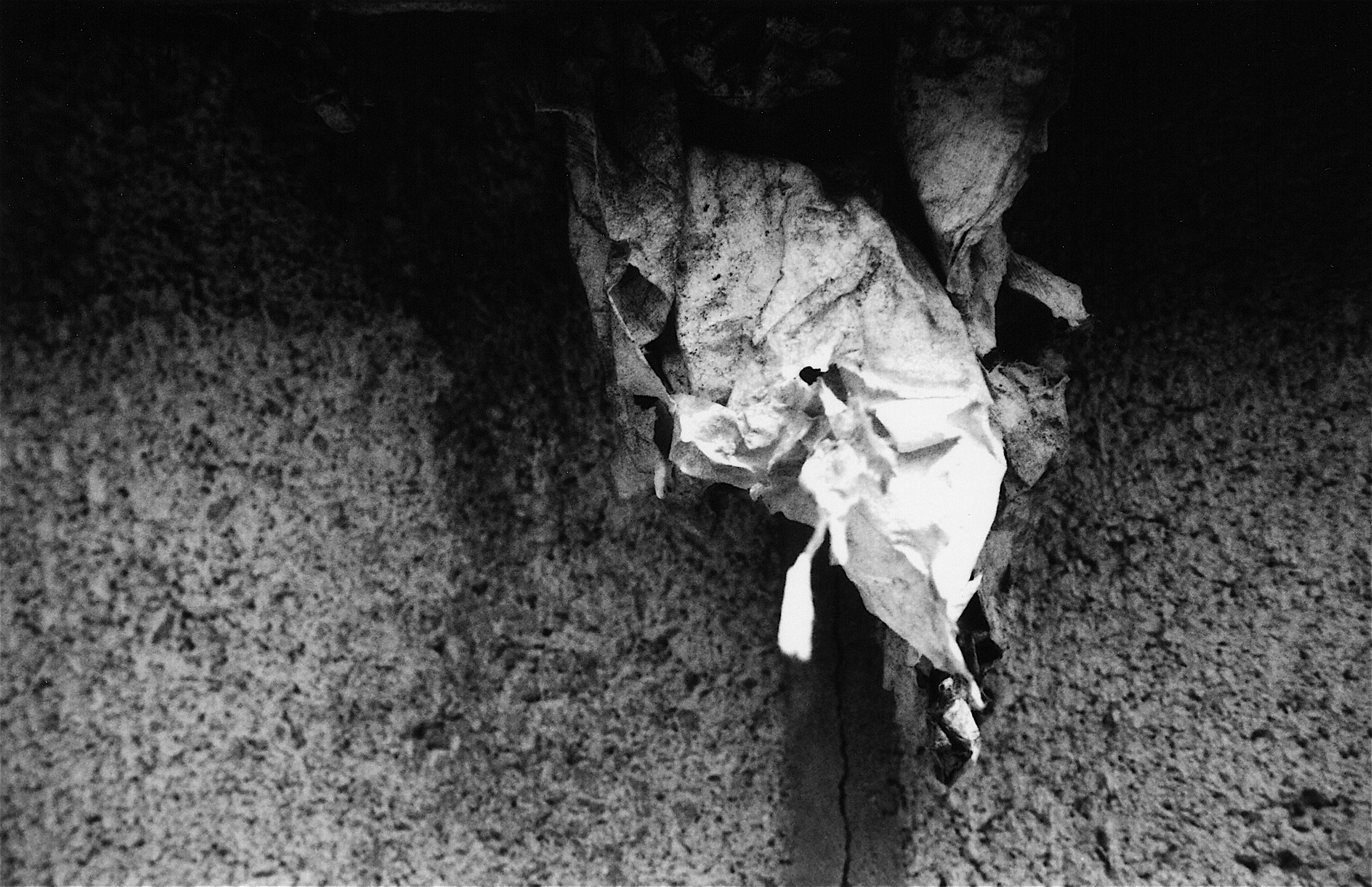

These are images from walks I've taken through Baltimore's streets and alleys. I find compositions, I do not arrange them, except in the viewfinder of my camera.

"The term desmoid originates from the Greek word "desmos", meaning band or tendon-like and was first applied in the 1800s to describe tumors with a tendon-like consistency." These tumors bind the connective tissues. They knot into themselves and pull the body's structures out of alignment. They mutilate and sometimes they kill. My desmoid tumors have come out of remission. I think of how these tumors have marked my flesh. I think of the many tissue stains that have gone into verifying my diagnosis. I look at the cellular structure of the tumors. I find these forms in the environment around me.

For me, these images represent the new constraints my body is experiencing, the shape of the disease. Things unravel for us all at times and we patch together our lives as best we can.

"The term desmoid originates from the Greek word "desmos", meaning band or tendon-like and was first applied in the 1800s to describe tumors with a tendon-like consistency." These tumors bind the connective tissues. They knot into themselves and pull the body's structures out of alignment. They mutilate and sometimes they kill. My desmoid tumors have come out of remission. I think of how these tumors have marked my flesh. I think of the many tissue stains that have gone into verifying my diagnosis. I look at the cellular structure of the tumors. I find these forms in the environment around me.

For me, these images represent the new constraints my body is experiencing, the shape of the disease. Things unravel for us all at times and we patch together our lives as best we can.

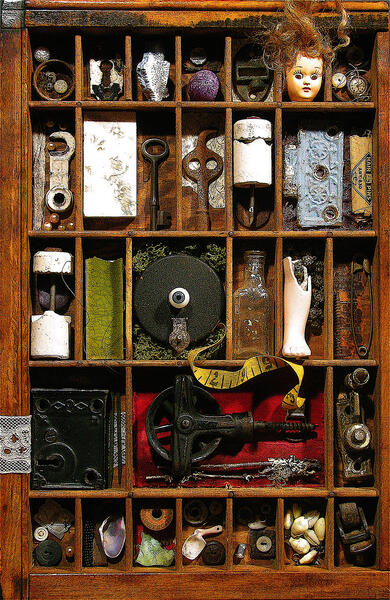

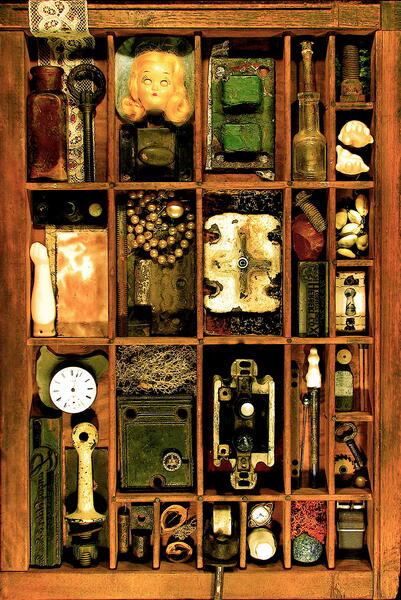

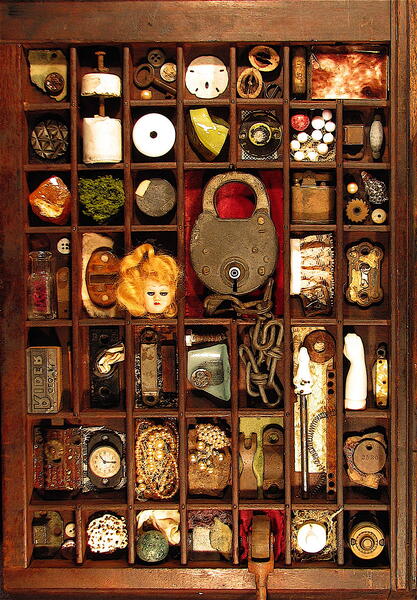

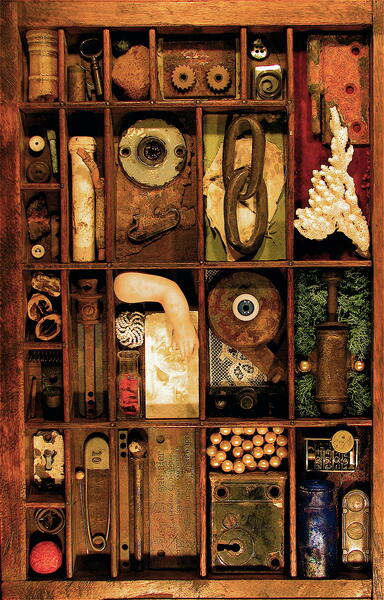

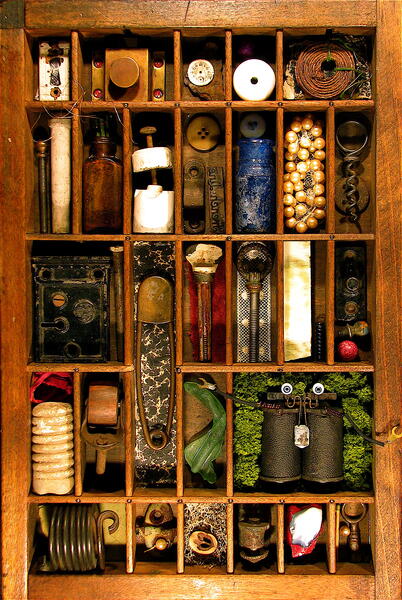

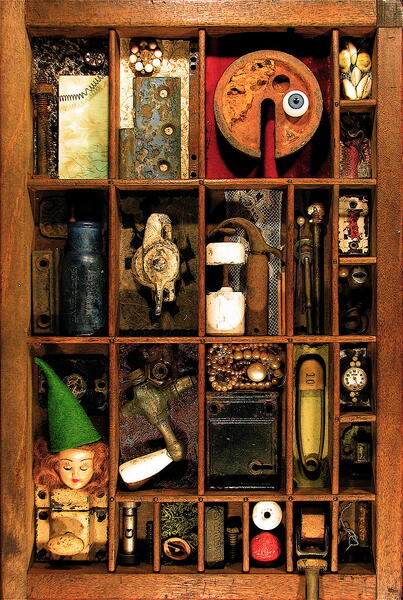

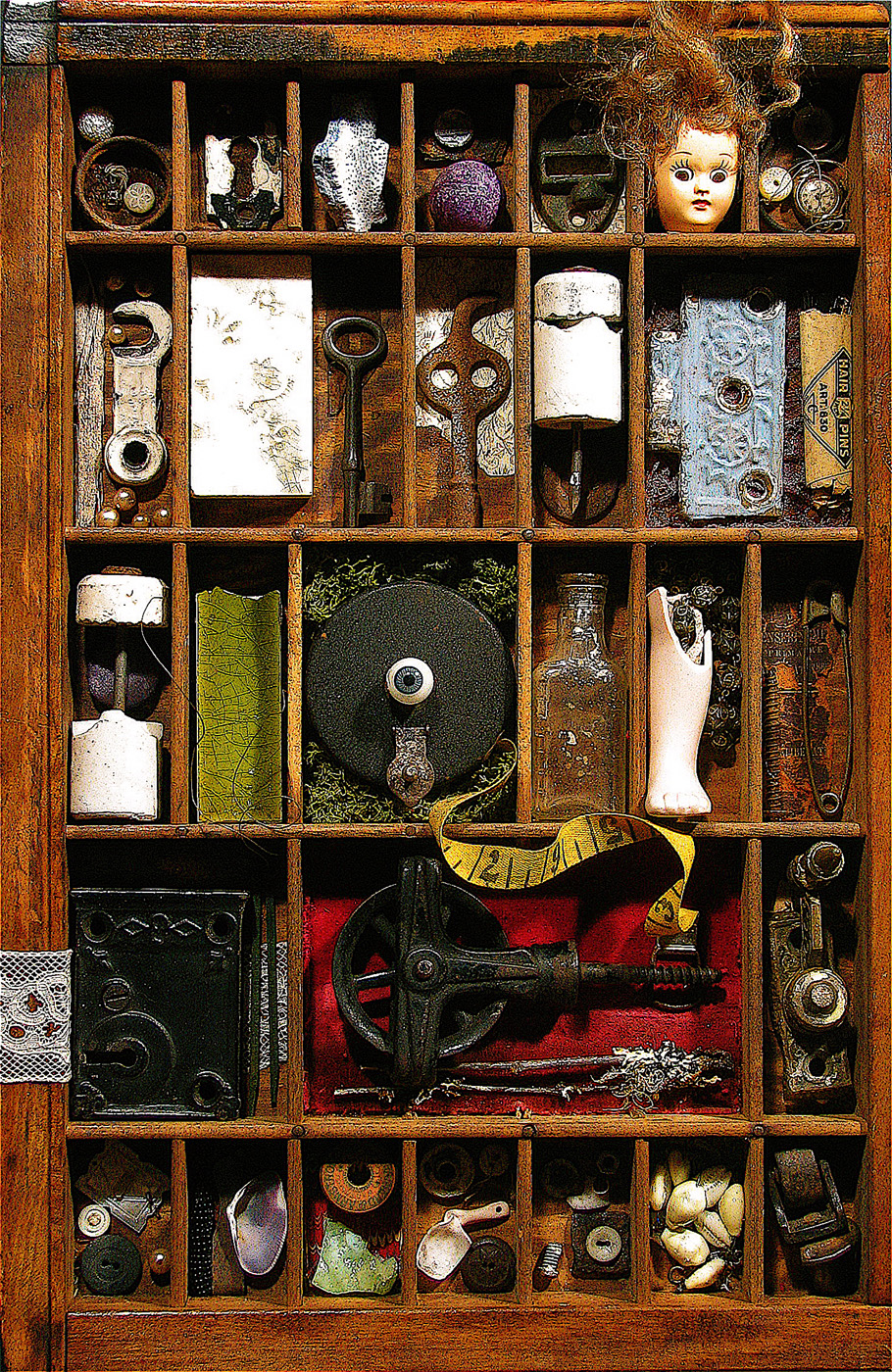

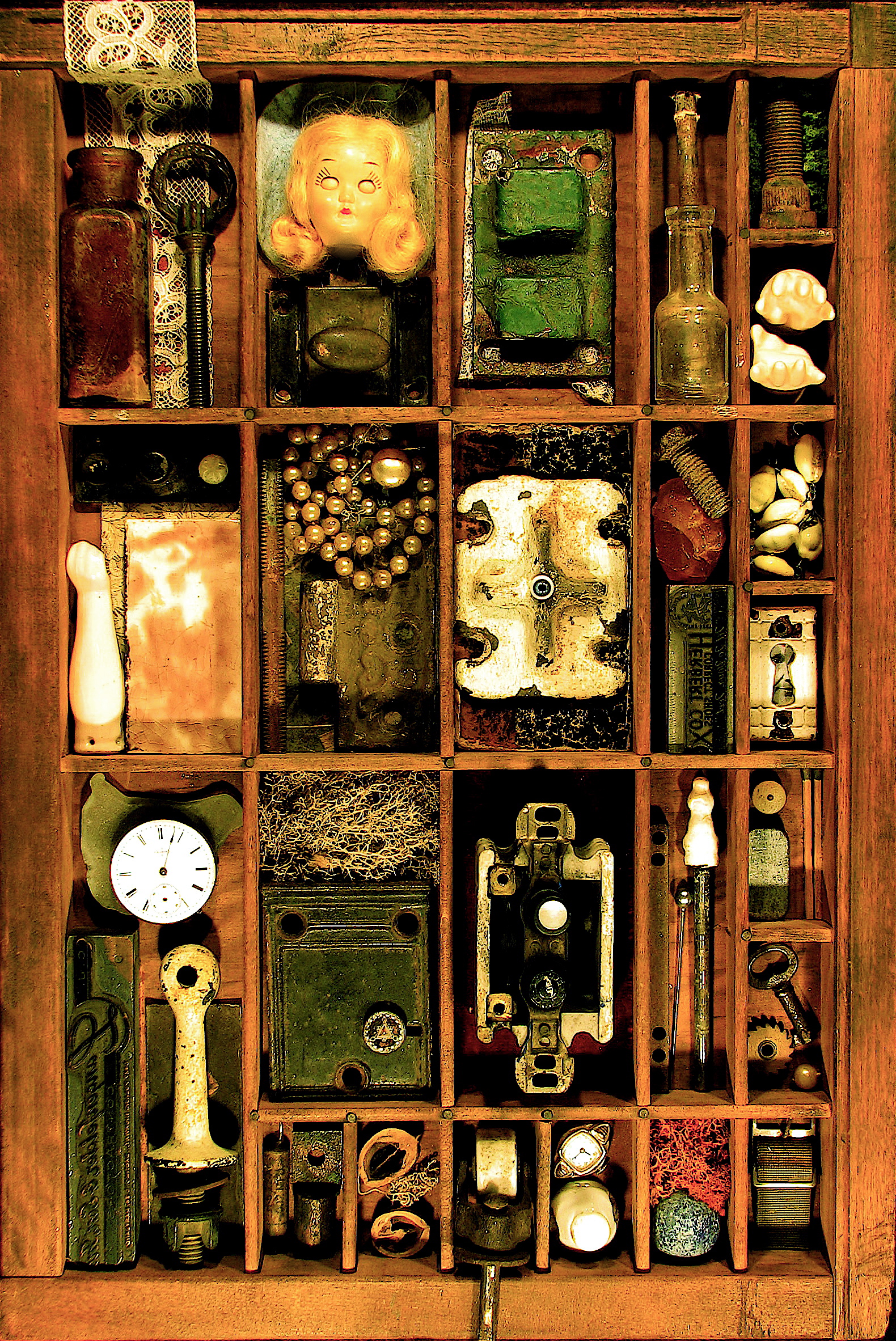

musing relics

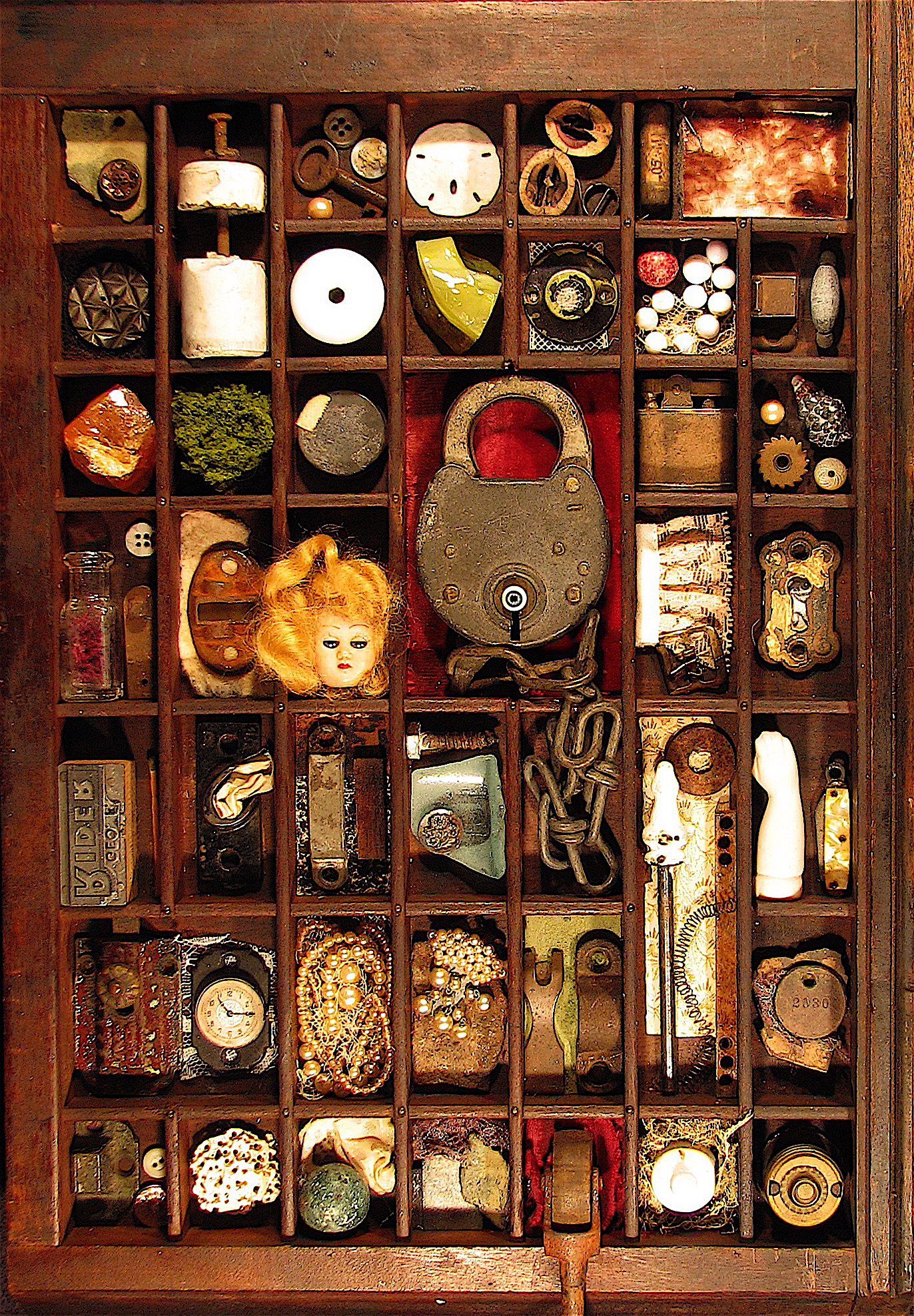

I have long been fascinated by the multiple orientations afforded by wonder cabinets, and I have been much inspired by Kurt Schwitters' exquisitely composed refuse, Joseph Cornell's theatrical boxes and Louise Nevelson's assembled abstracts. I collect found objects and play with their reactability in the studio/laboratory, intrigued both by what they disclose and by the investigation of infinitesimal qualities, Duchamp's inframince.

As a child, I explored the unfamiliar and forgotten objects cluttered in my parents' drawers. Many afternoon hours were spent guessing at their practical usage, often as not imagining unlikely ones and imbuing them with life. The fountain pen nibs, defunct cigarette lighters, sewing machine parts and broken jewelry were my "plastic animals." My father's horological tools were especially evocative, later I was entranced with his beautiful landscape designs. I read mythology with my brother Bob and appropriated the notion of composite beasts.

Contained within my pieces are vessels and aberrant anatomies, seemingly disparate objects enthralled by shared qualities. Contrasting textures compliment or irritate, there are harmonies and tensions. The life of objects reflects our own desires, sensuality and procreation and also what might be tangled, corroded or broken within. Process and transformation are revealed in decay, there are revelries to be found in dust.

As a child, I explored the unfamiliar and forgotten objects cluttered in my parents' drawers. Many afternoon hours were spent guessing at their practical usage, often as not imagining unlikely ones and imbuing them with life. The fountain pen nibs, defunct cigarette lighters, sewing machine parts and broken jewelry were my "plastic animals." My father's horological tools were especially evocative, later I was entranced with his beautiful landscape designs. I read mythology with my brother Bob and appropriated the notion of composite beasts.

Contained within my pieces are vessels and aberrant anatomies, seemingly disparate objects enthralled by shared qualities. Contrasting textures compliment or irritate, there are harmonies and tensions. The life of objects reflects our own desires, sensuality and procreation and also what might be tangled, corroded or broken within. Process and transformation are revealed in decay, there are revelries to be found in dust.