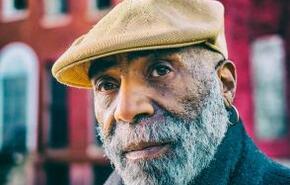

About Morgan

Born to a wealthy, established Creole family in Louisiana in 1945, I grew up attending segregated schools and attended Bishop College in Dallas, Texas, for three years before doing two tours of duty with the Navy in Vietnam between 1964 and 1973. When I returned home from Navy duty, curiosity as to my standing as a black man and an American citizen drove me to see how the rest of America lived. So, for 17 years thereafter, I… more

Black and Red: African Americans and Native Americans in the West

I grew up in Louisiana in a time when it was said that if you had just a drop of Negro blood you were black. I was eight years the summer I learned that I was also part Indian.

All that summer, our relatives kept arriving. I think my great-grandmother Nana knew she was dying, and she called her children and their families to pass along her blessing to them. They came from all over: Shreveport, Louisiana; Michigan; and Oregon. The cousins fit right in with the neighborhood kids, and every night after dinner we’d play cowboys and Indians. My friend Larry insisted on being the sheriff, because he had a badge. “There must be law and order in this black town,” he’d say.

It was my Uncle George who got us thinking about things. The first time I saw him, he was getting off the train in his cowboy boots and a big Mexican hat. He wore a gun belt but no guns. He was very tall and dark, with a big thick mustache, and when he walked he jangled. He smelled of cigars and rose water and sweat. I learned that night that he was Mama’s younger brother. He’d left home when he was thirteen, and had lived in Texas, California, and Mexico, where he owned a ranch.

Uncle George became a hero to us kids that summer. Every night he’d bring out a watermelon and talk to us about Mexico and its people, and about the West. He held us spellbound with his stories about cowboys and Indians, and our games took on a new life.

He started the other grownups talking, too. Mama told us about the Maroon people – fugitive slaves from the West Indies – in Florida. Our great-grandmother told us her mother was from the great Seminole nation that once ruled Florida, and she herself was the daughter of a Creek chief. My cousins and I realized that we had Indian blood in us, too.

One day Papa, my great-grandfather, came out of his workshop to stop a fight between a kid named Renard and my sister Elaine. Renard said there was no such thing as black soldiers in the West. We already knew better, but that day Papa told us about how the buffalo soldiers were called buffalo soldiers because people thought their hair looked like a buffalo’s mane.

Later that summer, Uncle Joe and Uncle George took us kids to Texas to see our first black rodeo. We knew about rodeos, but we had never heard of one where all the cowboys were black. I saw bulldogging for the first time. When we got home, I tried it on my dog Jeff, and he bit me.

That summer helped me see the connection between our games of cowboys and Indians – and the Wild West of the movies – and a history in which my family had a place. It showed me that our heritage included Native Americans, too, and it sparked my lifelong fascination with the West, which I’ve tried to capture in these portraits.

Taken from the book My Heroes, My People by Morgan Monceaux and Ruth Katcher, published by Frances Foster Books in 1999.

-

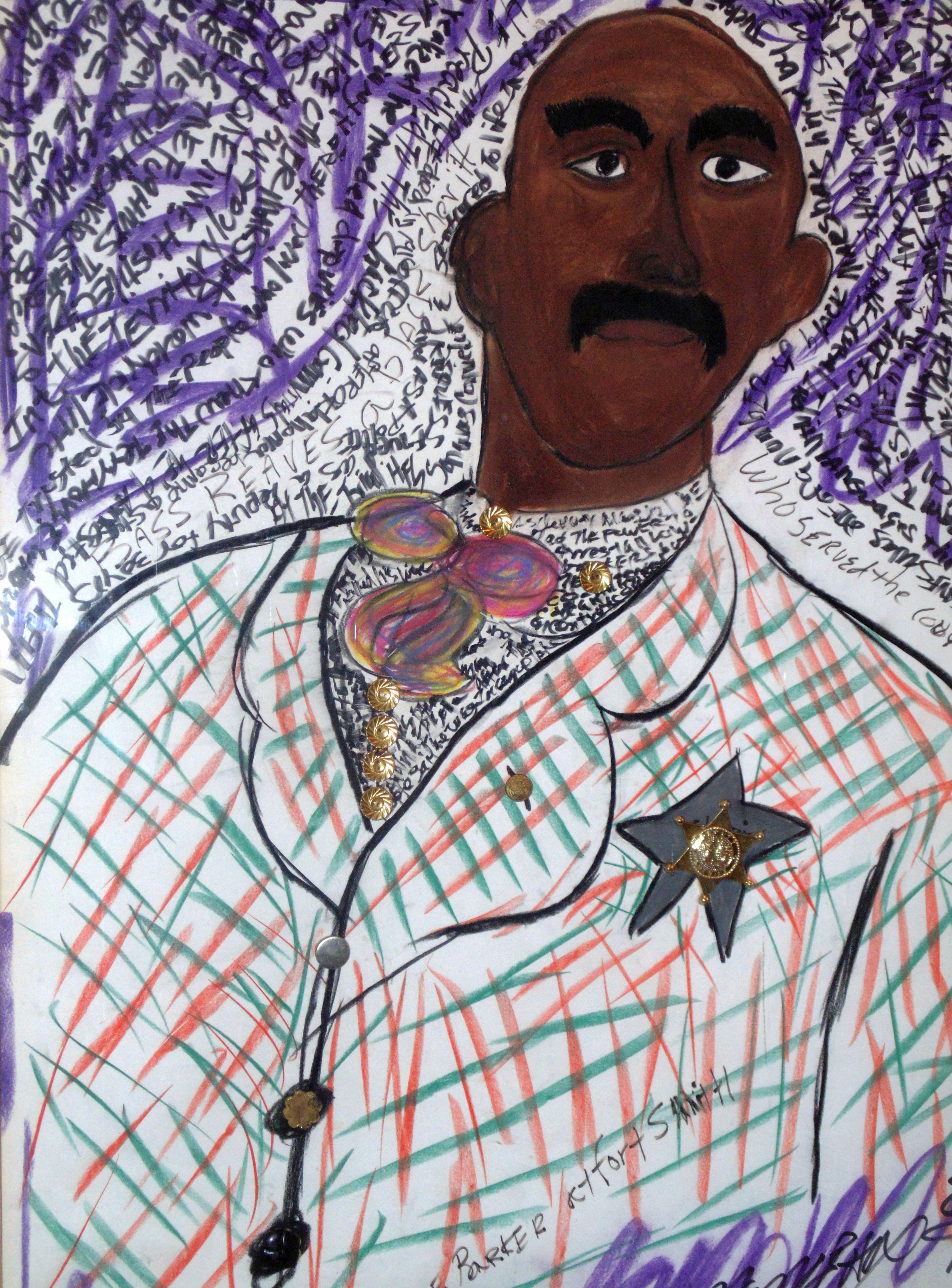

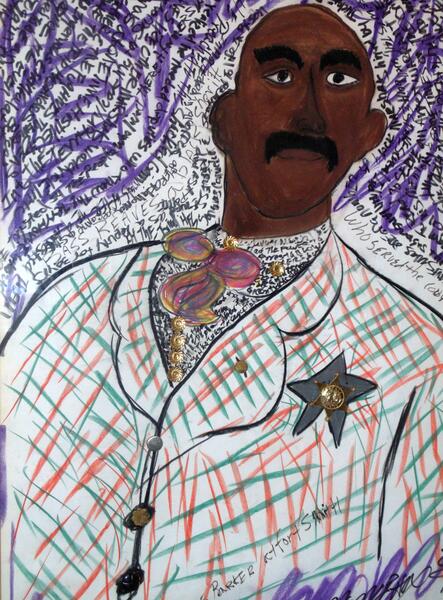

Bass ReevesA black marshall of whom it was said that he preached to shackled criminals after he arrested them. 40in x 30in. Mixed media on paper with found objects.

Bass ReevesA black marshall of whom it was said that he preached to shackled criminals after he arrested them. 40in x 30in. Mixed media on paper with found objects. -

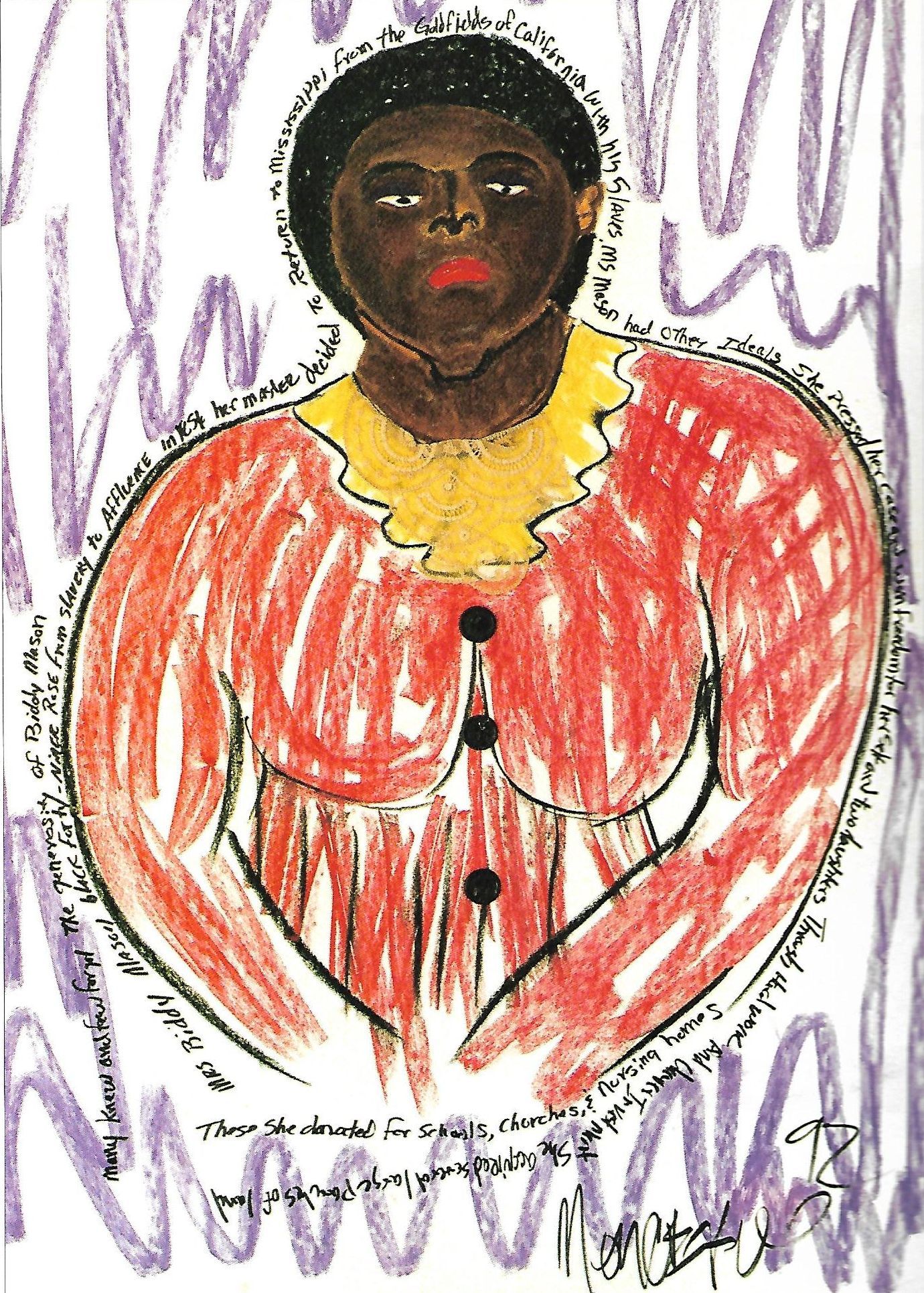

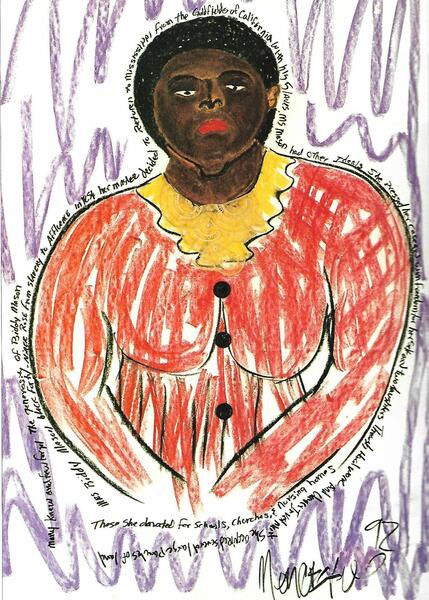

Biddy MasonA slave who became a woman of property. 40in x 30in. Mixed media on paper with found objects.

Biddy MasonA slave who became a woman of property. 40in x 30in. Mixed media on paper with found objects. -

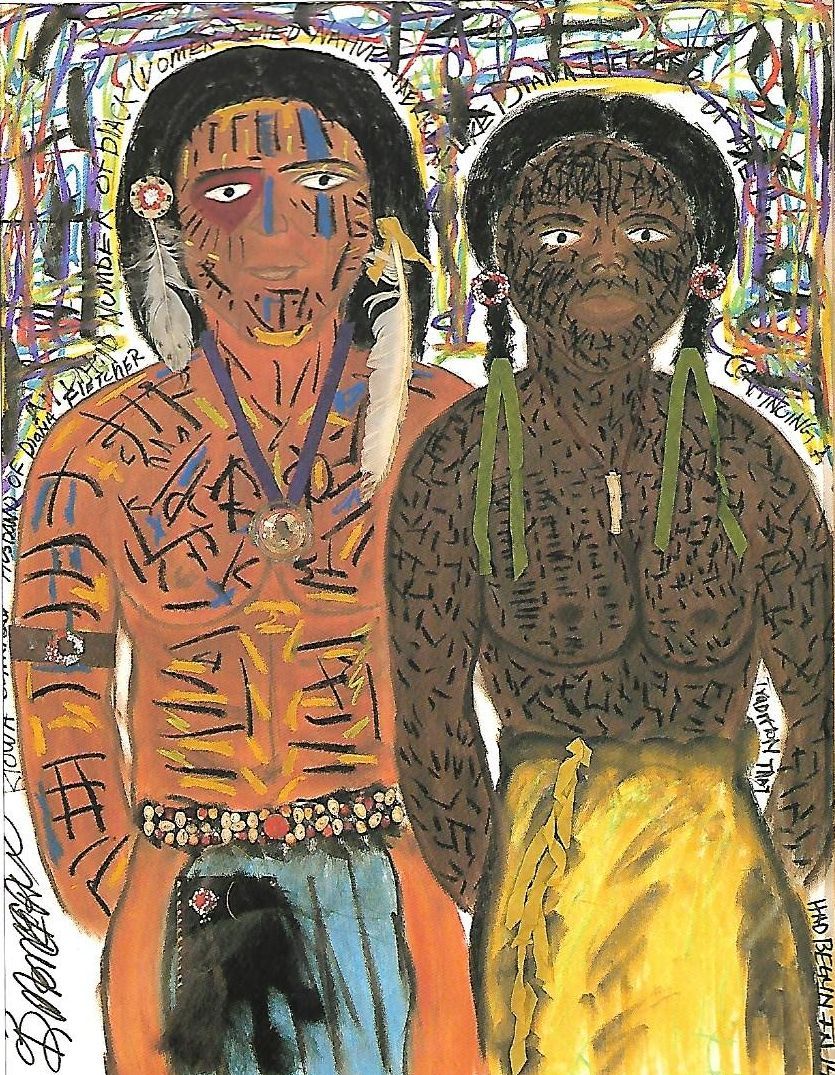

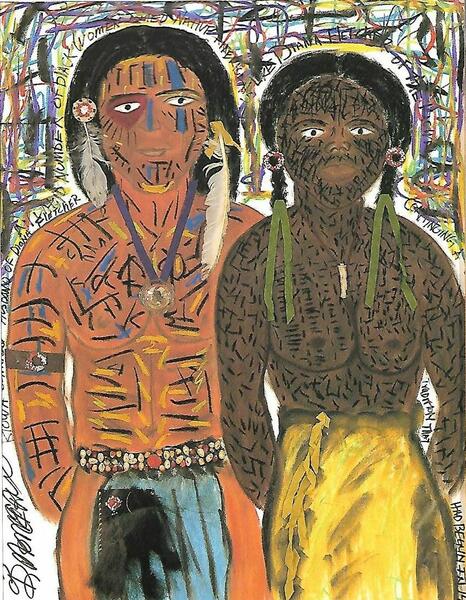

Diana FletcherA black woman who married a Kiowa Indian and lived with the Kiowa. 40in x 30in. Mixed media on paper with found objects.

Diana FletcherA black woman who married a Kiowa Indian and lived with the Kiowa. 40in x 30in. Mixed media on paper with found objects. -

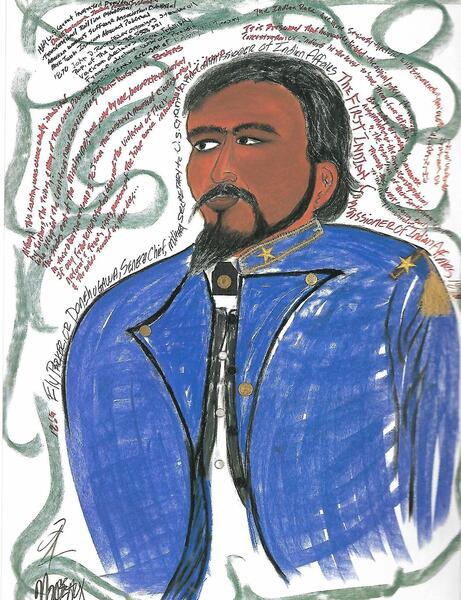

Ely ParkerA lawyer who couldn't argue a case in court because he was an Indian. 40in x 30in. Mixed media on paper with found objects.

Ely ParkerA lawyer who couldn't argue a case in court because he was an Indian. 40in x 30in. Mixed media on paper with found objects. -

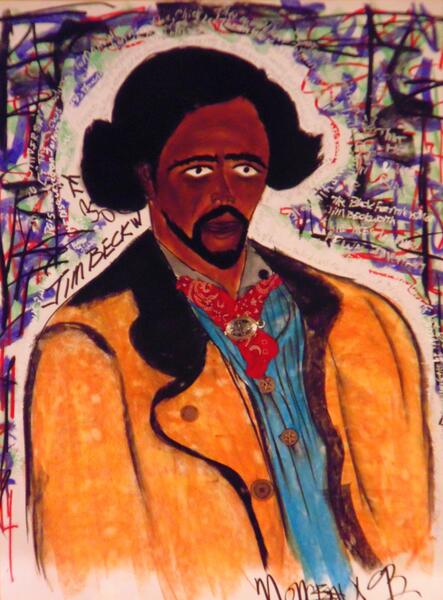

Jim BeckwourthThe slave who became a Crow chief and discovered a passage to the Far West. 40in x 30in. Mixed media on paper with found objects.

Jim BeckwourthThe slave who became a Crow chief and discovered a passage to the Far West. 40in x 30in. Mixed media on paper with found objects. -

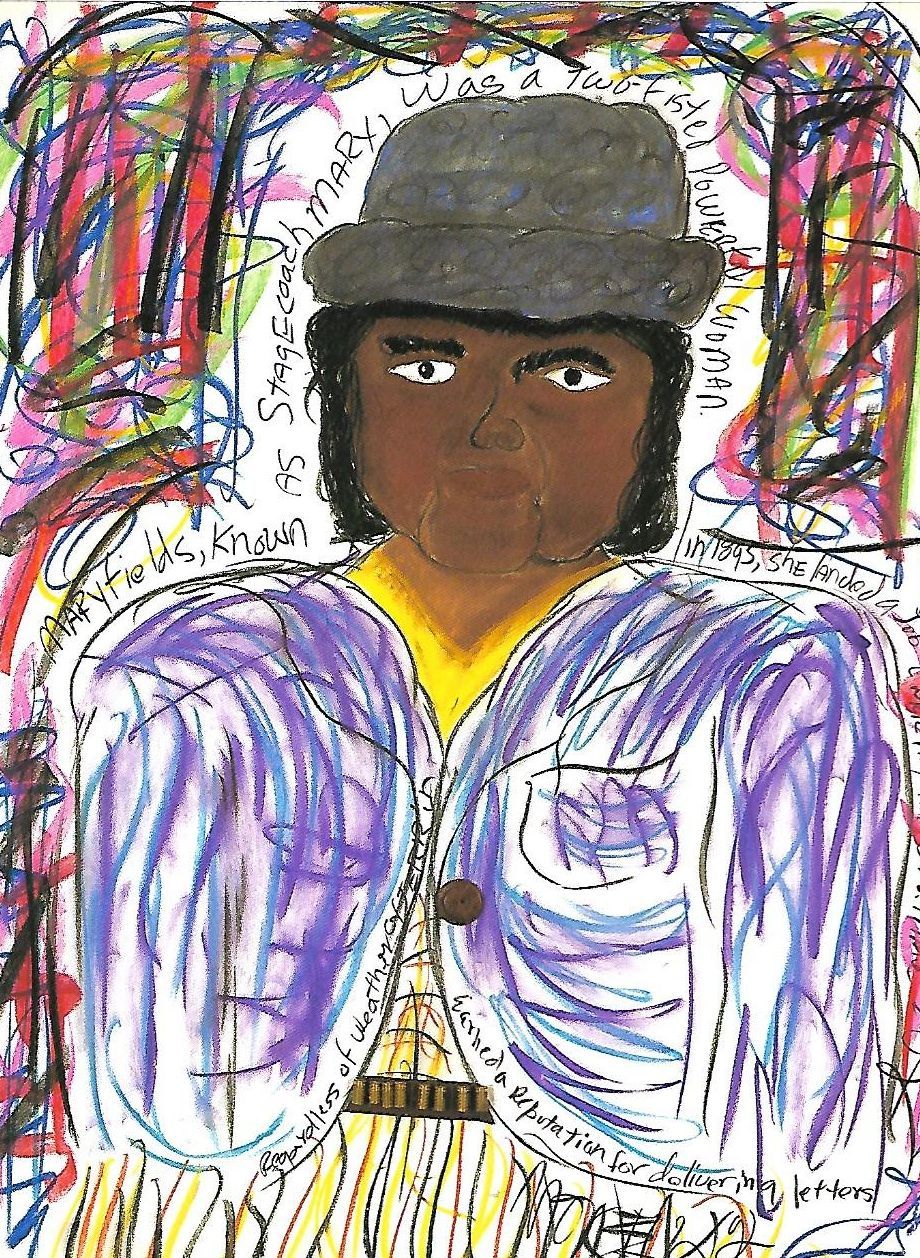

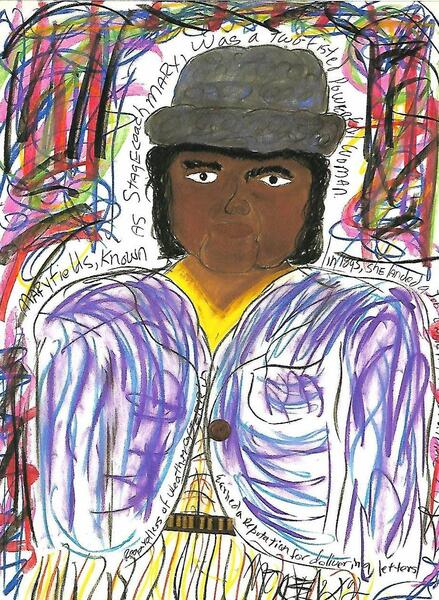

Mary FieldsAlso known as "Stagecoach Mary", she was a mail carrier who also ran a restaurant. 40in x 30in. Mixed media on paper with found objects.

Mary FieldsAlso known as "Stagecoach Mary", she was a mail carrier who also ran a restaurant. 40in x 30in. Mixed media on paper with found objects. -

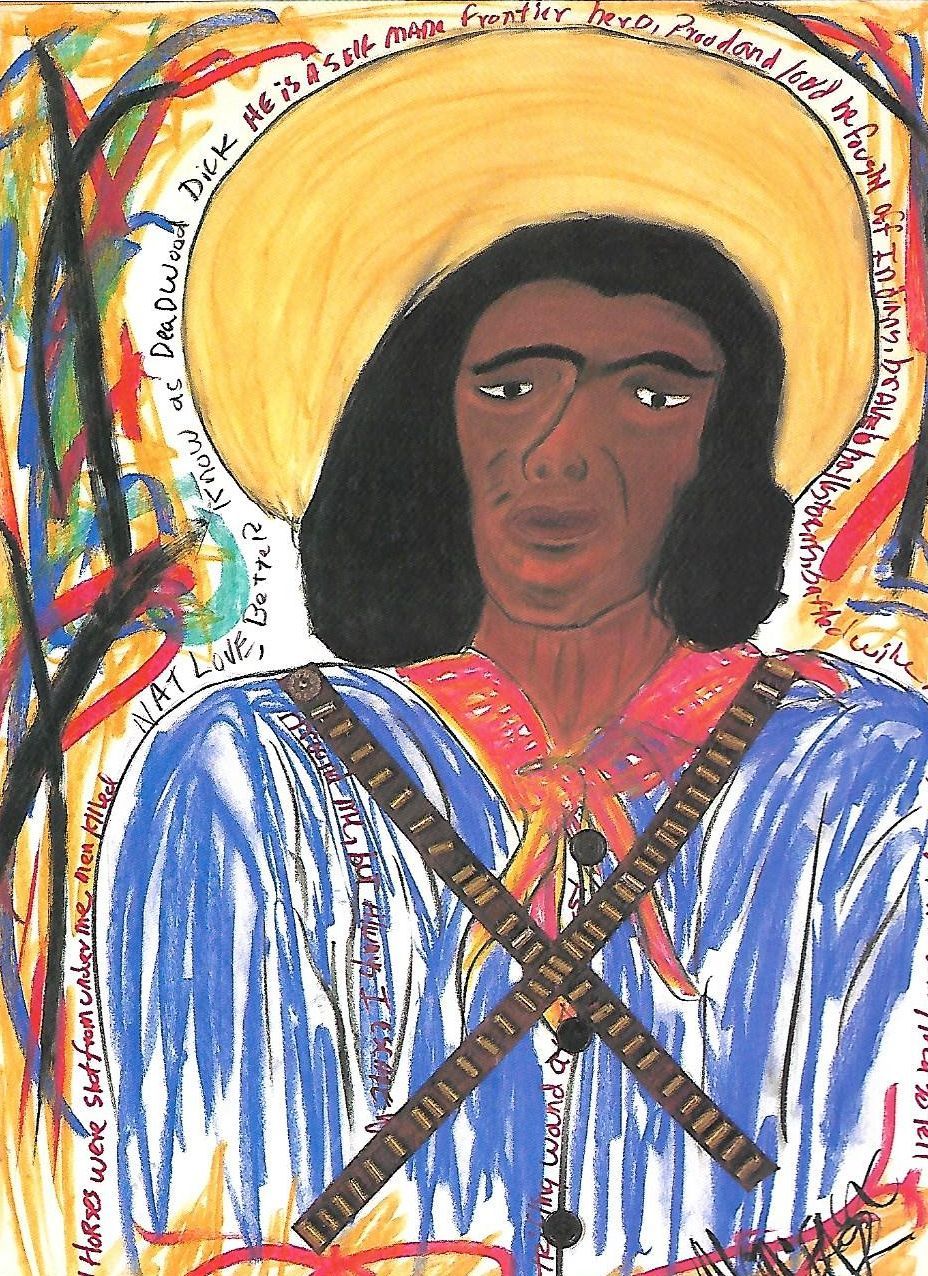

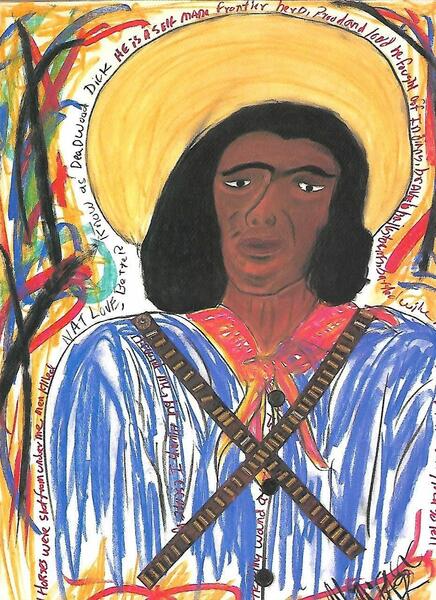

Nat Love"I was wild, reckless, and free, and afraid of nothing" 40in x 30in. Mixed media on paper with found objects

Nat Love"I was wild, reckless, and free, and afraid of nothing" 40in x 30in. Mixed media on paper with found objects -

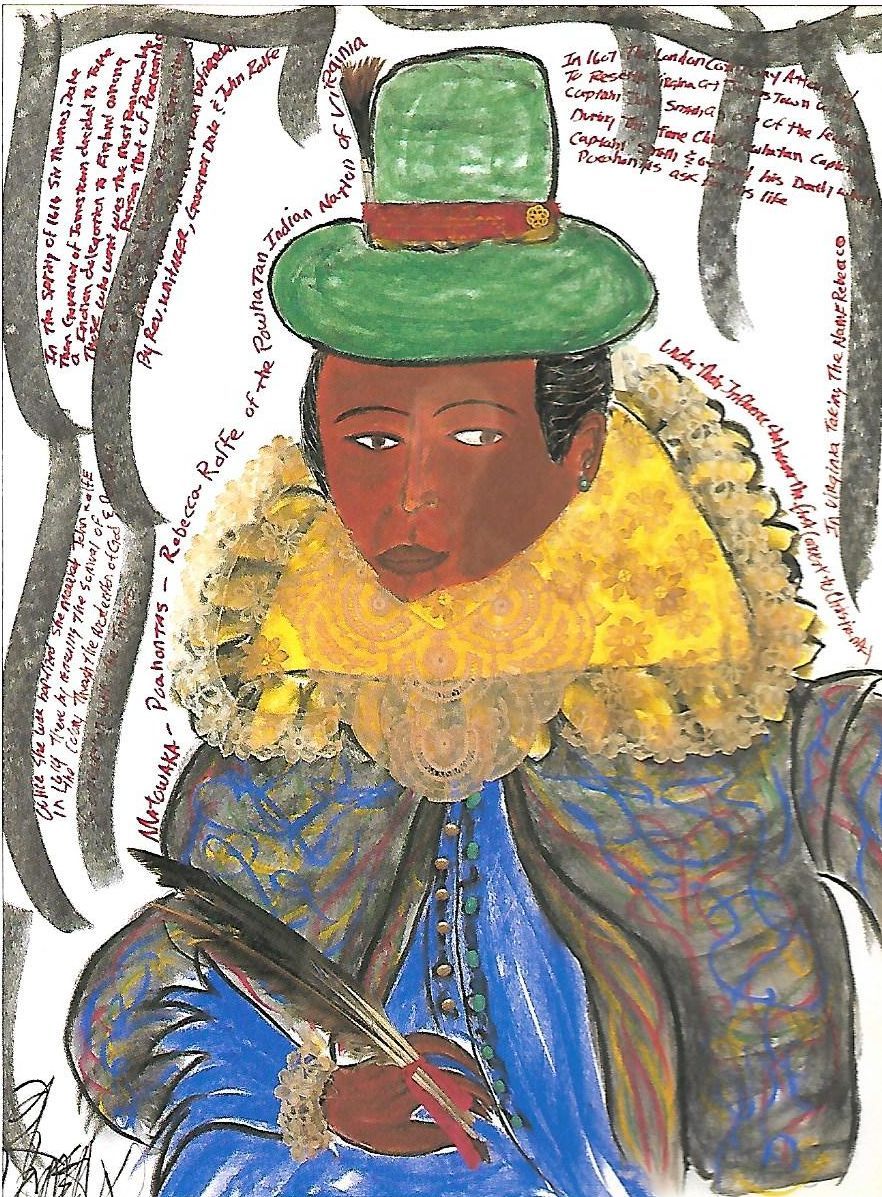

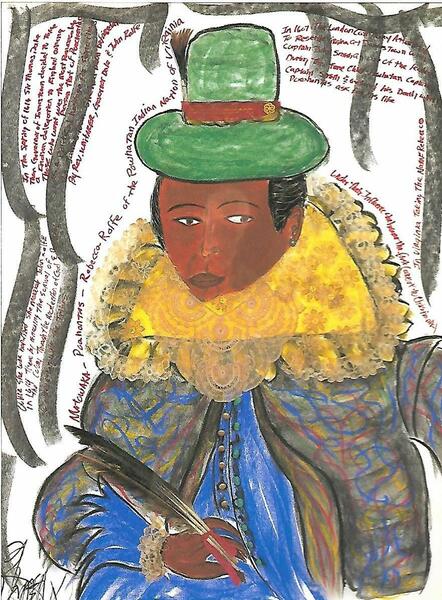

PocahontasThe Indian princess who became an English lady. This particular work was cited in Heike Paul's "The Myths That Made America" (published by [transcript], Germany, in 2014). 40in x 30in. Mixed media on paper with found objects.

PocahontasThe Indian princess who became an English lady. This particular work was cited in Heike Paul's "The Myths That Made America" (published by [transcript], Germany, in 2014). 40in x 30in. Mixed media on paper with found objects. -

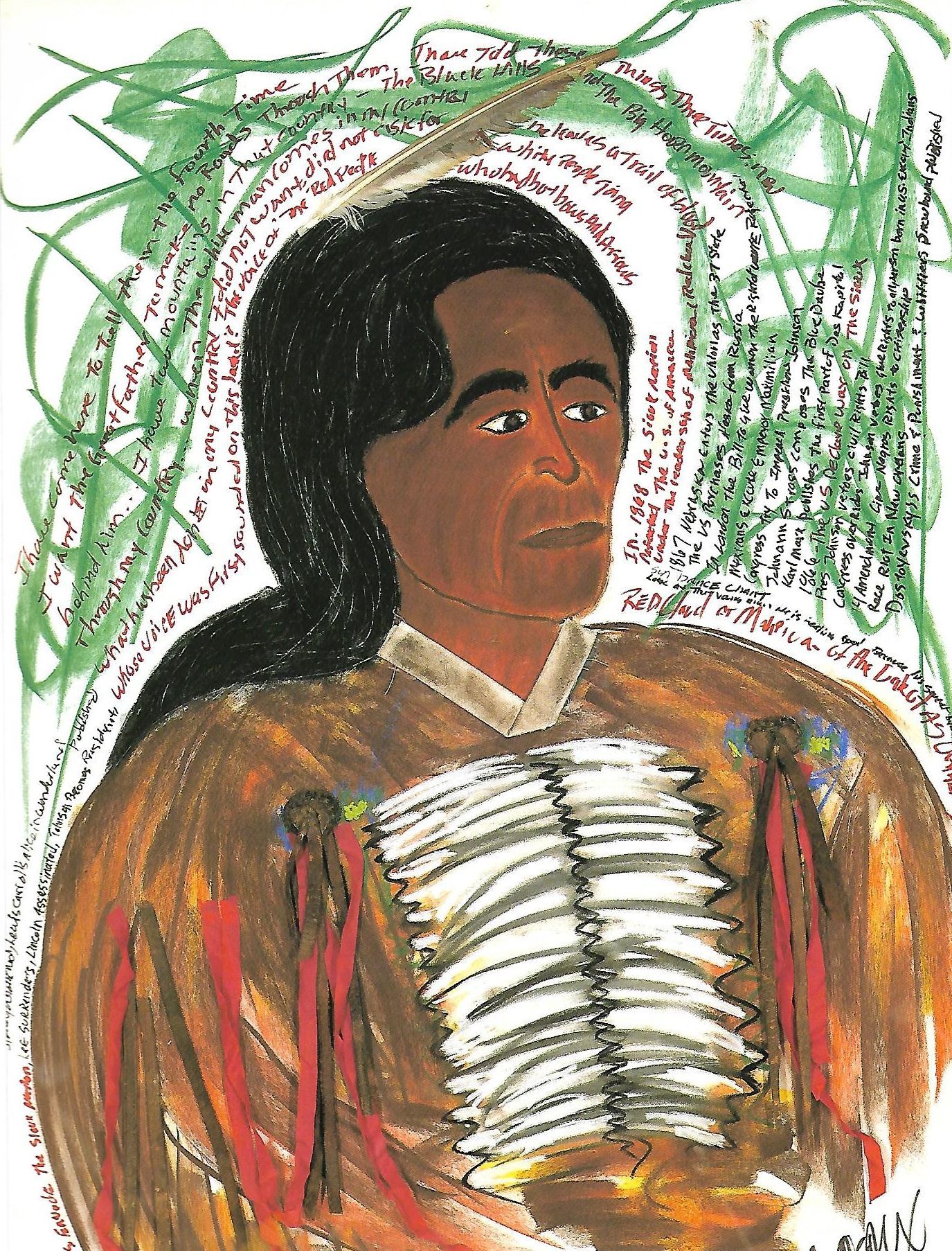

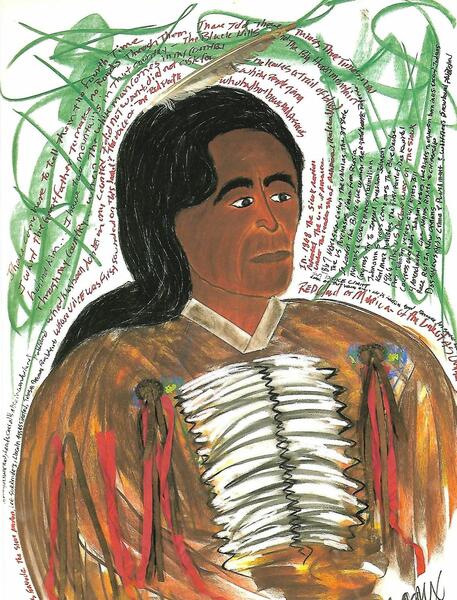

Red Cloud"The white children have surrounded me and left me nothing but an island" 40in x 30in. Mixed media on paper with found objects.

Red Cloud"The white children have surrounded me and left me nothing but an island" 40in x 30in. Mixed media on paper with found objects. -

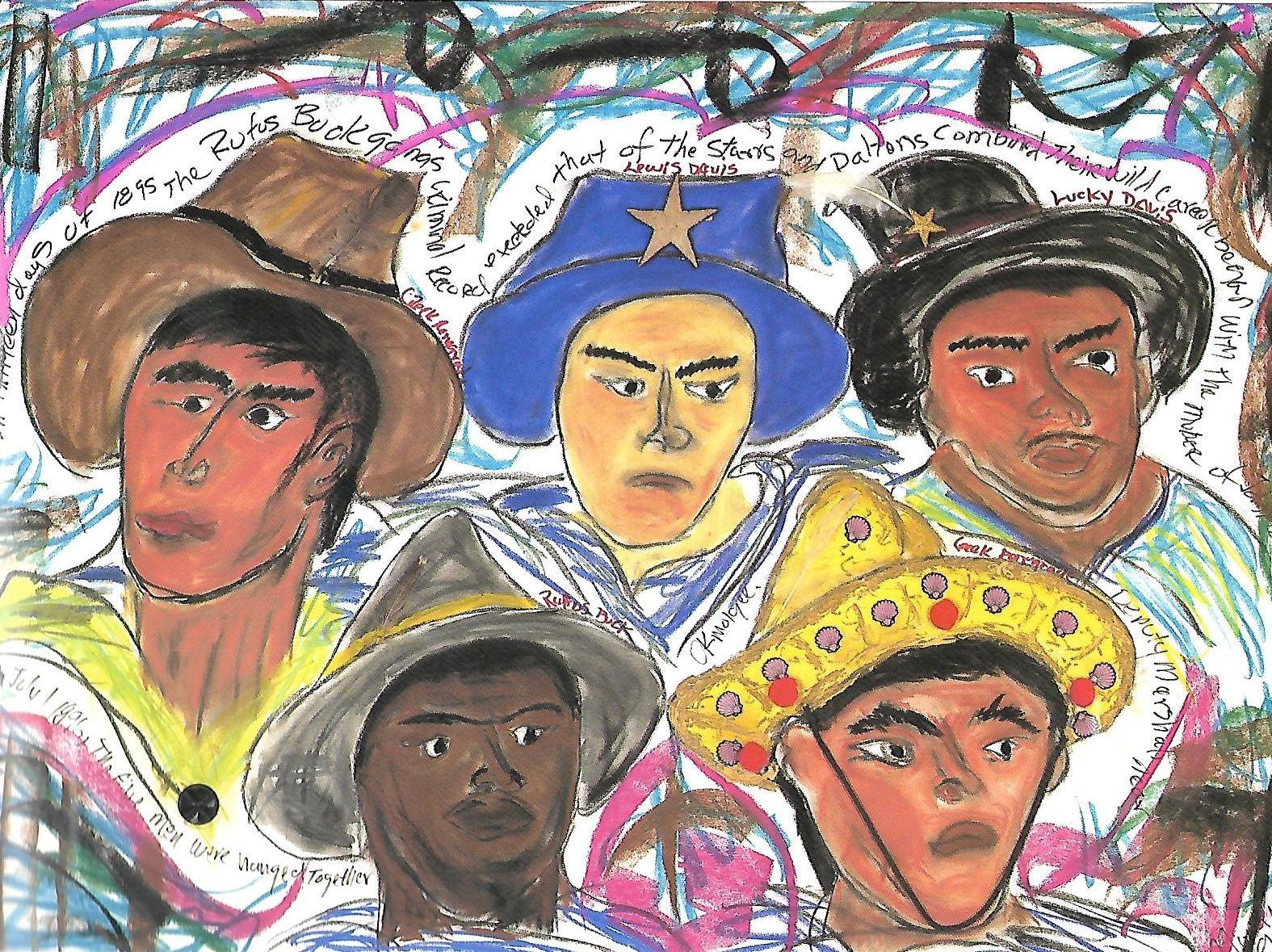

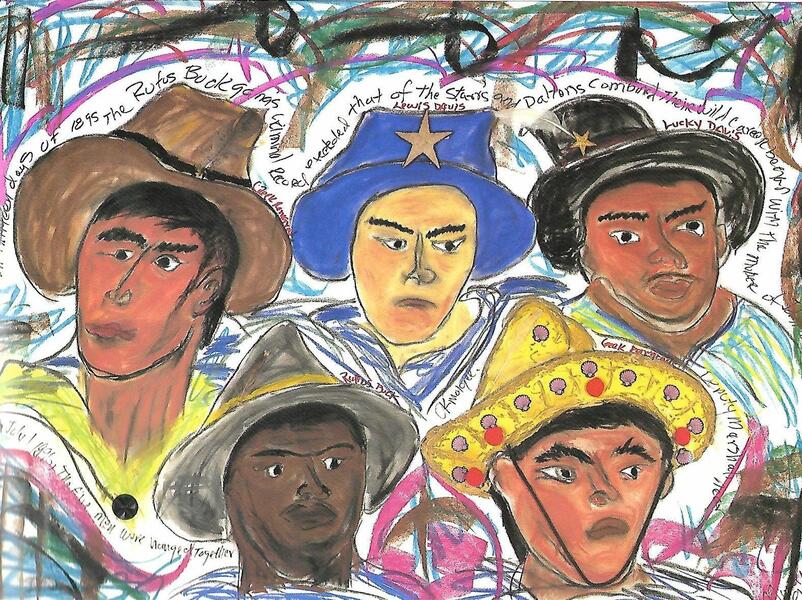

The Rufus Buck GangTrue outlaws. 30in x 40in. Mixed media on paper with found objects.

The Rufus Buck GangTrue outlaws. 30in x 40in. Mixed media on paper with found objects.

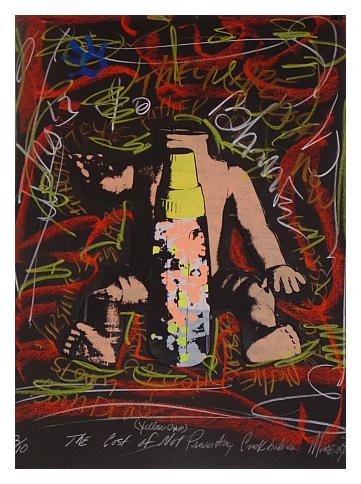

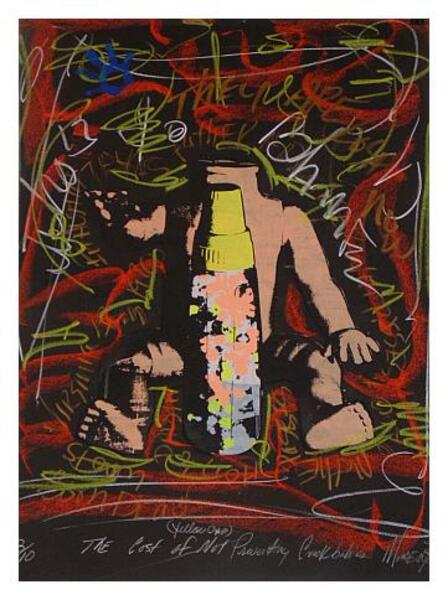

The Cost of Not Preventing Crack Babies

This exhibition and performance is based on the universal theme of human frailty, tragedy and suffering - art reflects life. You, the viewer, as participants, are challenged to respond, to be alive and to value humankind.

My intention was to draw attention to the problem of crack addiction and to highlight where the responsibility lies.

This piece was first performed at Artscape 2003 in Baltimore. The format was that of a funeral, complete with readings, personal testimonials and a final procession. Included within the space were headless baby dolls, drug paraphernalia and a coffin.

Originally recorded on VHS.

-

Crack BabiesThis is an installation performance piece incorporating headless baby dolls, entitled "The Cost of Not Preventing Crack Babies".

-

Baby's Feeding BottleBaby's feeding bottle containing found objects

Baby's Feeding BottleBaby's feeding bottle containing found objects -

Dark Headless DollHeadless doll

Dark Headless DollHeadless doll -

Crack Babies Silkscreen Print40in x 30in. Silkscreen print.

Crack Babies Silkscreen Print40in x 30in. Silkscreen print. -

crack_babies1.mp3This is an excerpt from an hour-long CD that accompanies the Crack Babies installation performance piece. The title is "Crack Attack" by Grace Jones which comes from the 1989 album "Bulletproof Heart" on the Capitol label.

And So I Sing

The following piece was originally written by Robert Dilworth, Professor of Art at the University of Rhode Island in 1999. It has been adapted to reflect the work that is being shown in this portfolio.

We all know the music of black people. Music that comes from the deep bowels of the black soul. Music that began in a distant land, its syncopation and rhythm redefined in the fields of the southern delta in times almost forgotten. Music played in the juke joints and crowded shacks along narrow winding Mississippi roads. Music re-tempo-ed and re-issued to fill the dance halls and night clubs of northern cities. Music modified and echoed by almost every known popular musician. Some called it Boogie Woogie, some called it Bebop, some called it Jazz, some called it Blues, some call it Hip Hop and some call it House. It all comes from the same place. It all resonates with the same cultural and emotional urgency. The souls of black folk remain deeply embedded in this music. The soul of America is irrefutably shaped by it.

However, little is known about those black women in history who sang classical music. Those women who beat all odds to appear in recital halls and on operatic stages of the world. Who, through sheer talent and tenacity, out-maneuvered America's social and racial schizophrenia to be counted among the most gifted of classical singers. By all accounts they were exceptional. From Miriam Anderson, who was proclaimed by Toscanini as having a voice that is heard only once every hundred years, to Jessye Norman whose Olympian voice catapulted her to international fame in the early 80s. And there were others. In the nineteenth century – Sissieretta Jones, Elizabeth Taylor-Greenfield, Marie Selika, and the Hyers sisters, to those who came later such as Anne Brown, Camilla Williams, Dorothy Manor, Abbie Mitchell, Leontyne Price, Martina Arroyo, and Kathleen Battle, to name a few. Thus, the wave of black operatic and recital stars was relentless.

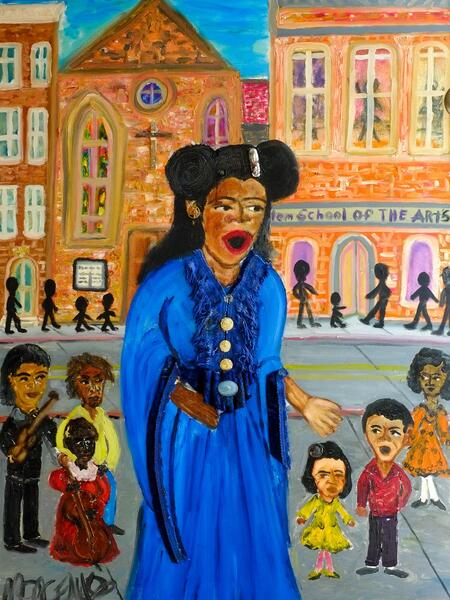

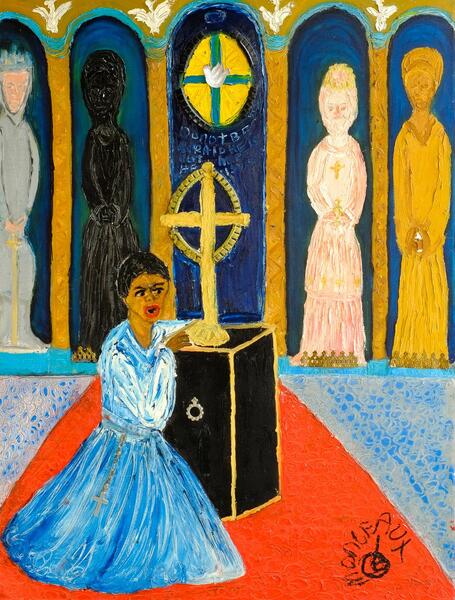

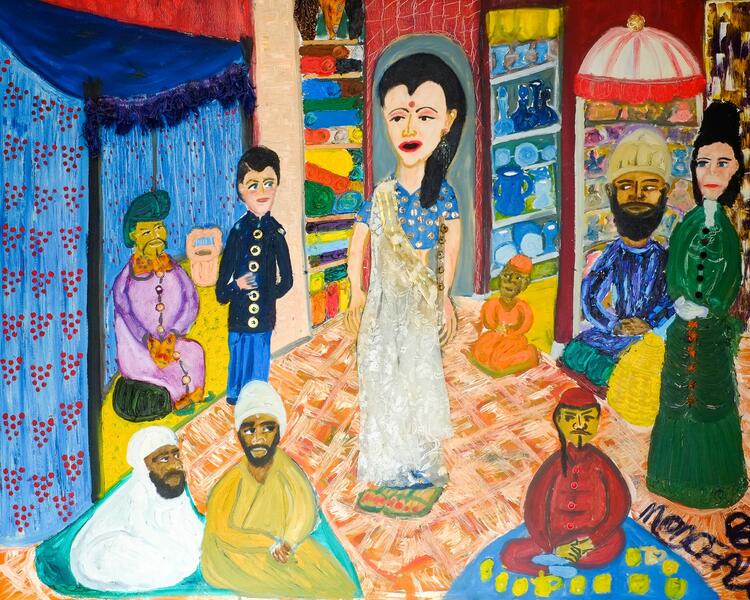

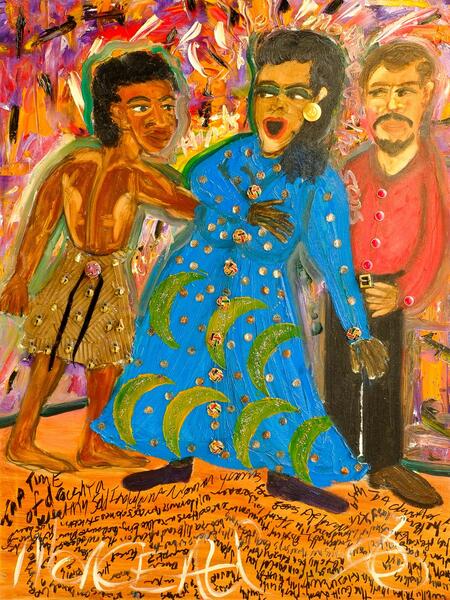

In Morgan Monceaux's collection of oils on canvas entitled “And So I Sing”, he pays homage to the women who were triumphant in this music. “Divas”, he calls them, and divas they are.

But what is a diva, a black diva in particular? What separates her from all other singers, many of whom sing the same songs but do not reach “diva” status? In other words, what are the primary ingredients in becoming and remaining a diva? The textbook definition is taken from the Latin word meaning “goddess, or divine one”. These questions led me to think of ten points that all the women above and many others share. To me, in every case they (1) made themselves from scratch, (2) in their own way formed and defined the black female stage presence, (3) sacrificed all for their music, (4) confessed to no crimes of the heart, (5) instilled remembrance, (6) had no fear, (7) committed to love, (8) were real, (9) undressed and then re-outfitted the soul, and (10) created a safe harbor in us all.

They each are not just a mere object de luxe, as many would have them, but a particular embodiment of black cultural heritage. In short, they are a necessary part of defining the black cultural whole.

Throughout twentieth-century America artists have turned to musical forms such as jazz, blues, and classical music to inspire specific artworks or to be the models from which a work is shaped. Monceaux often uses music to provide a ground for his paintings, drawings and prints. This group of oil paintings testifies to his (then) ever-expanding range of images based on the continuing theme of Black Music America. Like Romare Bearden, William H. Johnson, Archibald Motley, and a host of other black artists before him, Monceaux explores and reconstructs the psychological underpinnings that has given rise to black music and that makes it so enduring. Using the elements of visual design and printmaking, then following through different aspects of the entire series with pastels and oils, he sifts through the interior spaces of black musical culture to form the corpus of “Divas”. Collectively, they constitute a world within itself.

These scenic portraits, categorized as “Divas Three”, place the subject in full professional perspective. The drama of stance, stage and costume are meticulously structured in support of the moment– the diva emerging mid-note, opulent and composed.

Clearly, Monceaux has given us an alternate vision of the “Diva”. These are not just depictions of singers who made musical history but women whose lives confronted and exemplified the conflicts of a world constantly changing. Perhaps the diva can be best summed up in a poem by Langston Hughes. In Down and Out Hughes writes:

If you loves me

Help me when I'm down an' out

If you loves me

Help me when I'm down an' out.

Cause I'm a po' gal that

Nobody gives a damn about.

-

Divas VoiceoversThese voice-overs are taken from a 3-CD compilation of music that accompanied the original exhibition of the Divas series. The compilations feature women that I consider to be modern "divas", regardless of music genre.

-

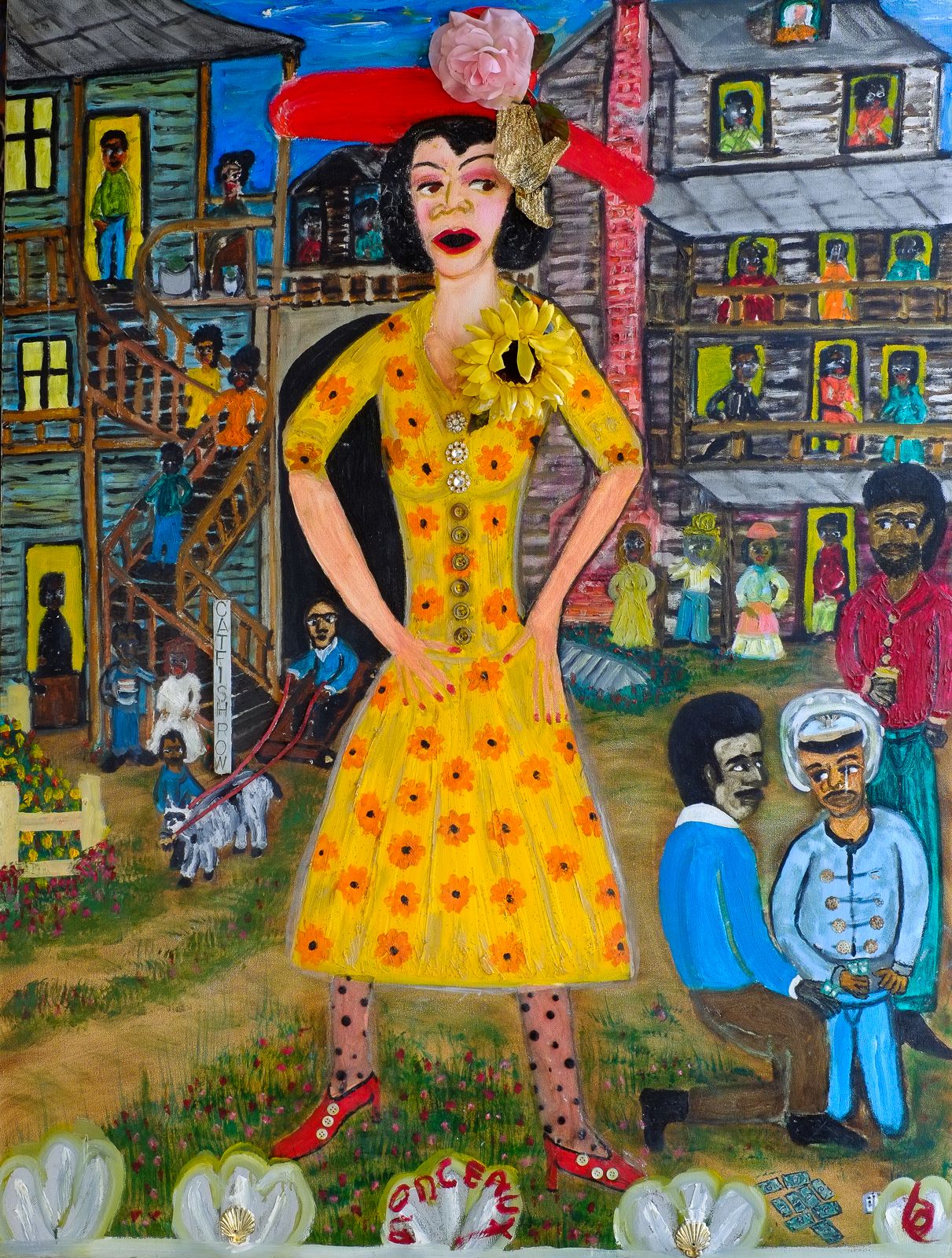

Anne Brown as BessAnne Brown, a native of Baltimore, was the first "Bess" from "Porgy and Bess" by Gershwin. 40in x 30in. Oils and mixed media with found objects on canvas.

Anne Brown as BessAnne Brown, a native of Baltimore, was the first "Bess" from "Porgy and Bess" by Gershwin. 40in x 30in. Oils and mixed media with found objects on canvas. -

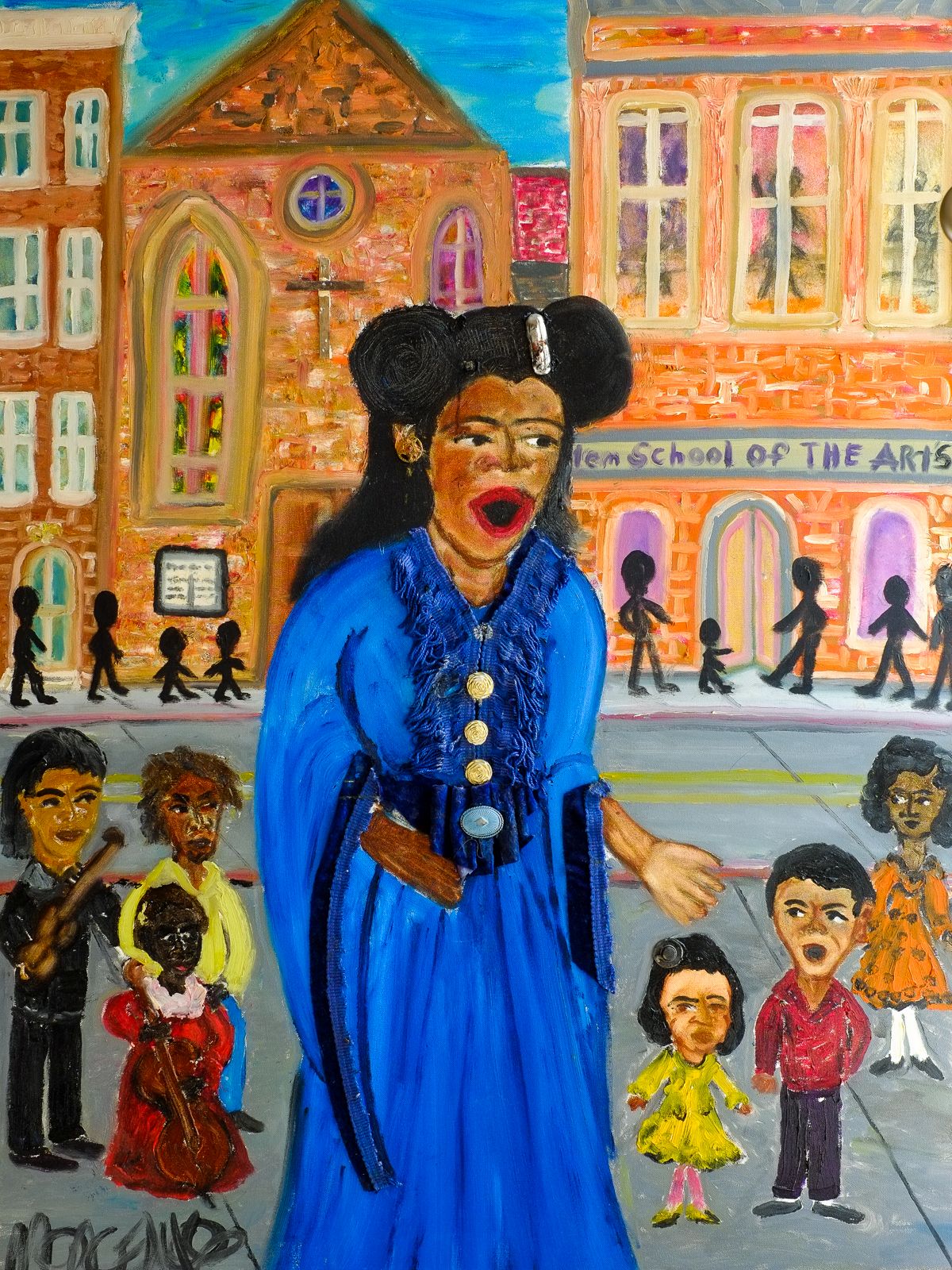

Dorothy Maynor40in x 30in. Oils and mixed media with found objects on canvas.

Dorothy Maynor40in x 30in. Oils and mixed media with found objects on canvas. -

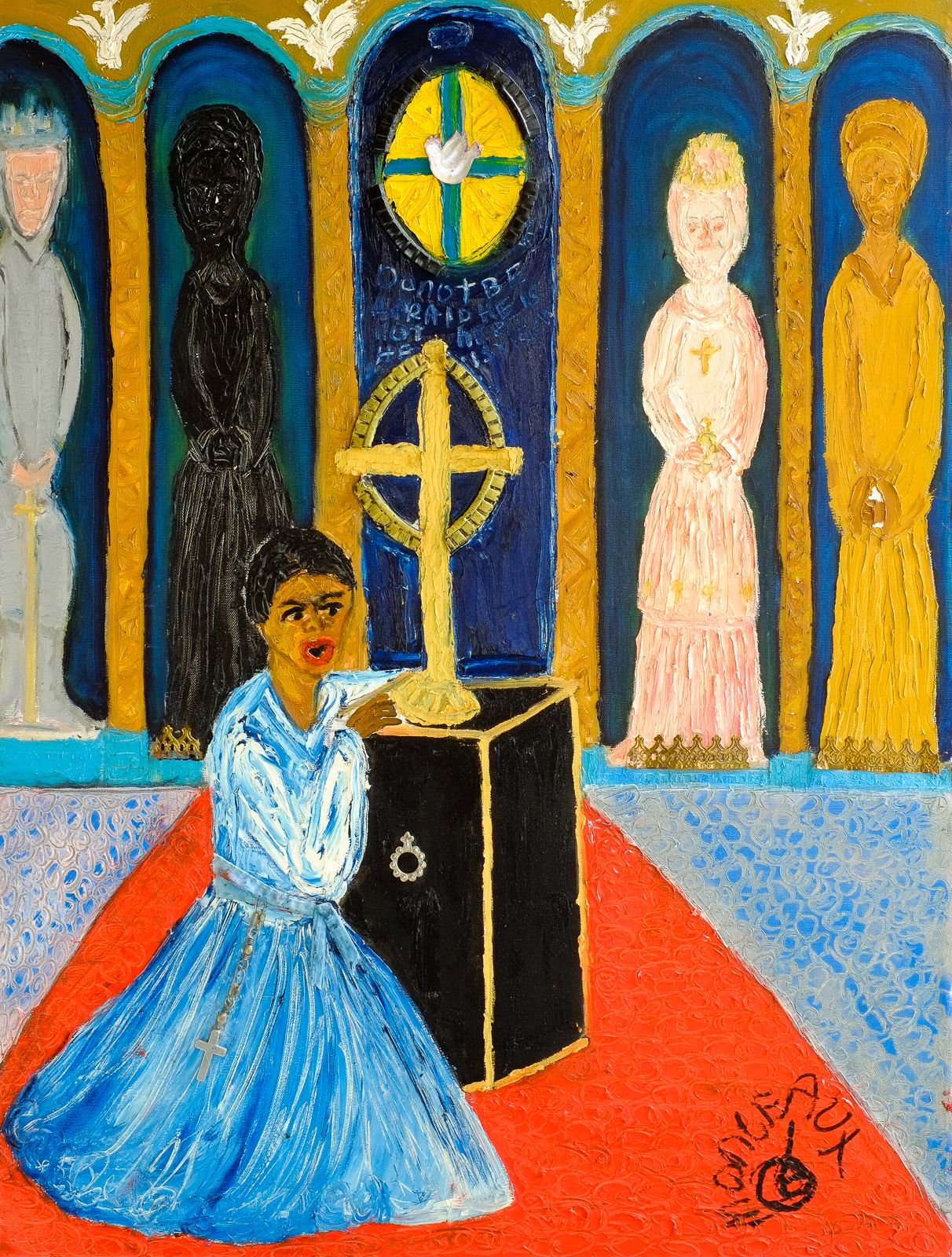

Elizabeth Taylor-Greenfield at Covent Garden Before Queen VictoriaThe first black person to perform before royalty. 40in x 30in. Oils and mixed media with found objects on canvas.

Elizabeth Taylor-Greenfield at Covent Garden Before Queen VictoriaThe first black person to perform before royalty. 40in x 30in. Oils and mixed media with found objects on canvas. -

Grace Bumbry as The Black Swan in Wagner's Tannhauser40in x 30in. Oils and mixed media with found objects on canvas.

Grace Bumbry as The Black Swan in Wagner's Tannhauser40in x 30in. Oils and mixed media with found objects on canvas. -

Hilda Harris in the Martyrdom of Saint Magnus40in x 30in. Oils and mixed media with found objects on canvas.

Hilda Harris in the Martyrdom of Saint Magnus40in x 30in. Oils and mixed media with found objects on canvas. -

Lillian Evanti48in x 60in. Oils and mixed media with found objects on canvas.

Lillian Evanti48in x 60in. Oils and mixed media with found objects on canvas. -

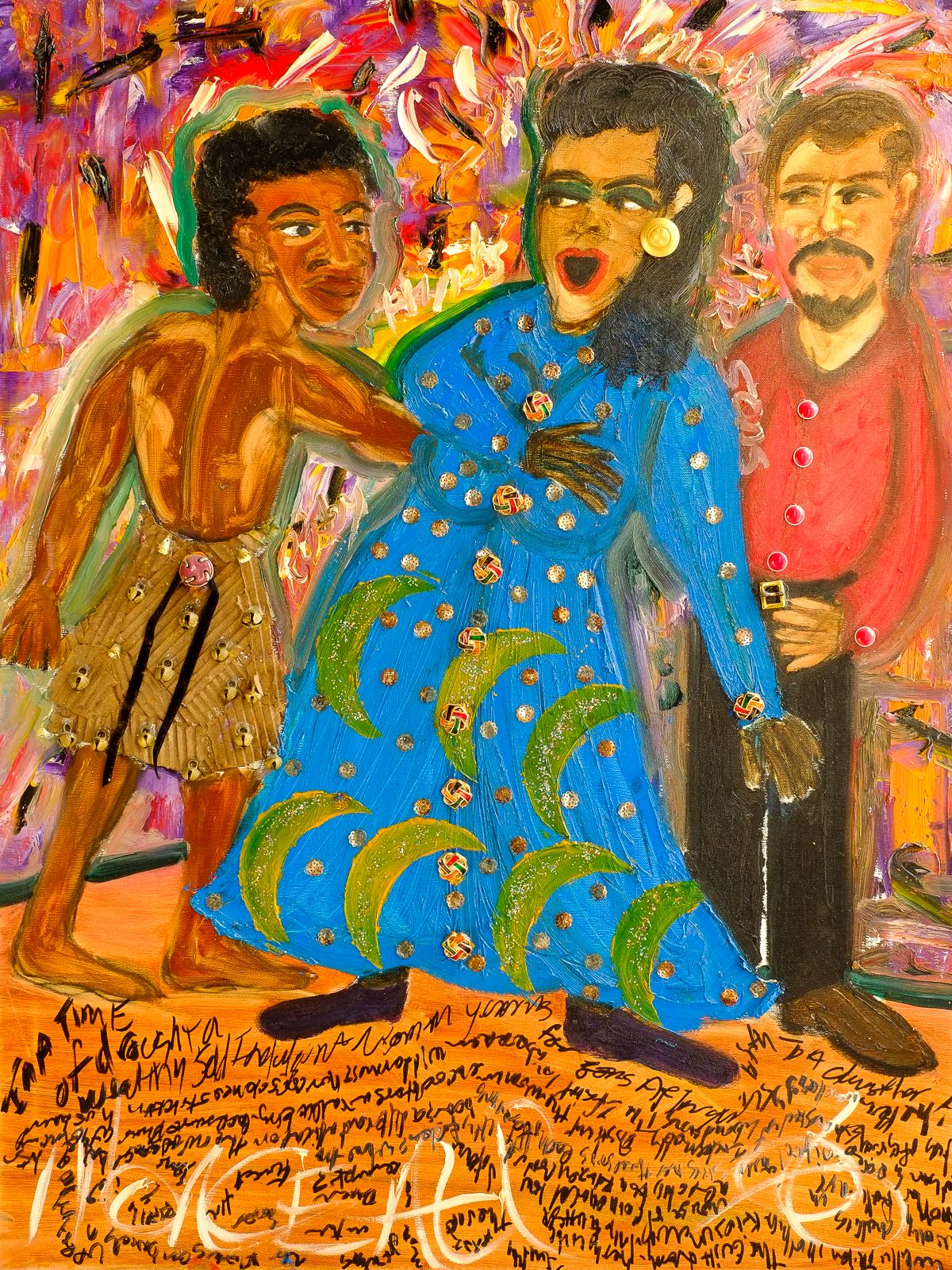

Ruby Hinds in A Mother And Her Three Sons by Bill T JonesThis dance/opera was inspired by folktales from sub-Saharan Africa. 40in x 30in. Oils and mixed media with found objects on canvas.

Ruby Hinds in A Mother And Her Three Sons by Bill T JonesThis dance/opera was inspired by folktales from sub-Saharan Africa. 40in x 30in. Oils and mixed media with found objects on canvas. -

Shirley Verrett as Carmen40in x 30in. Oils and mixed media with found objects on canvas.

Shirley Verrett as Carmen40in x 30in. Oils and mixed media with found objects on canvas. -

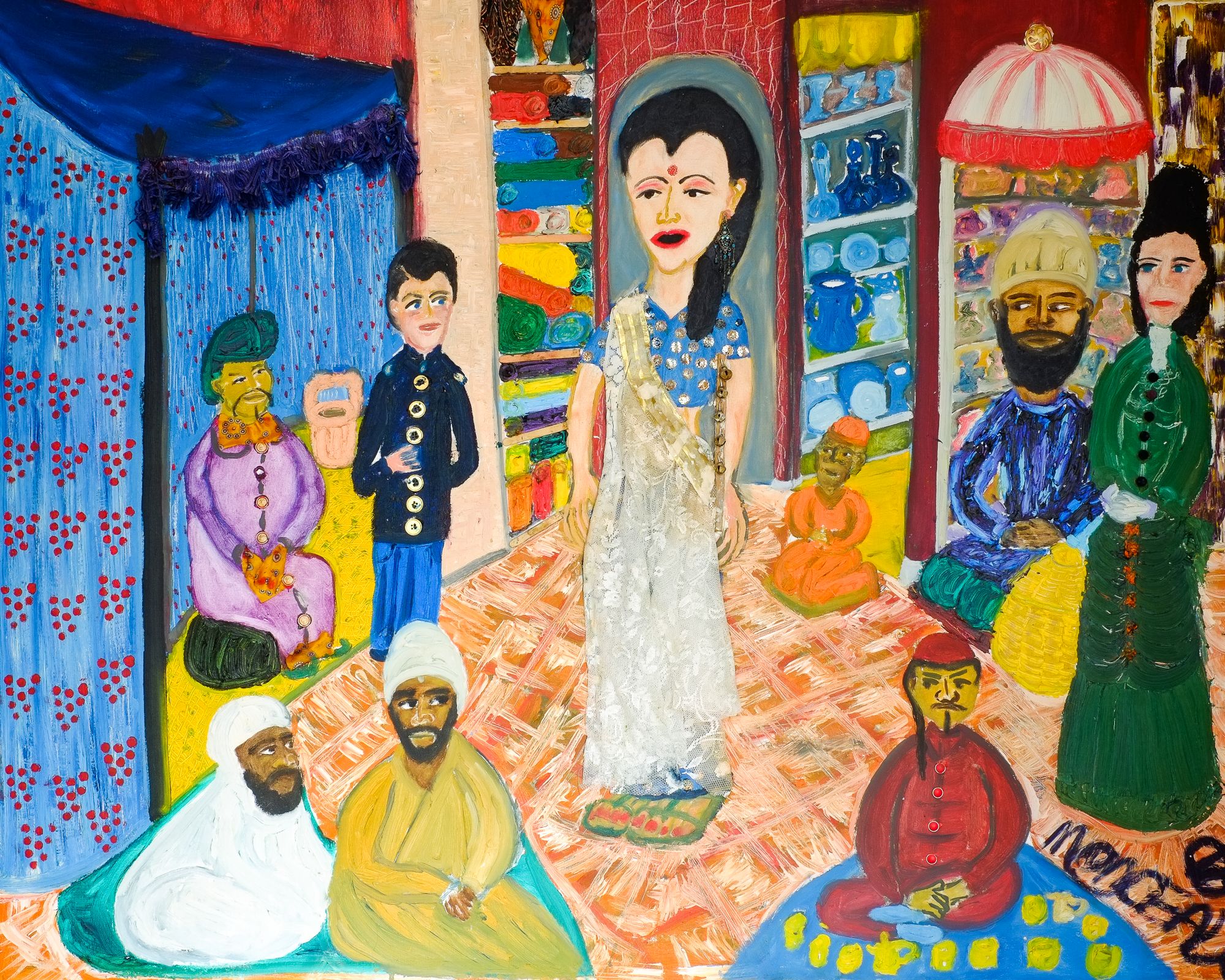

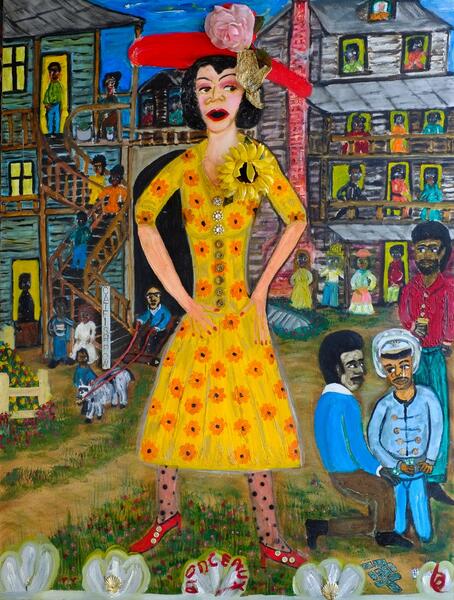

Sissieretta Jones Sings Home Sweet Home In The Blue Room48in x 60in. Oils and mixed media with found objects on canvas.

Sissieretta Jones Sings Home Sweet Home In The Blue Room48in x 60in. Oils and mixed media with found objects on canvas.