Work samples

-

Foreign Objects: The Transformation of a Greenlandic Landscape

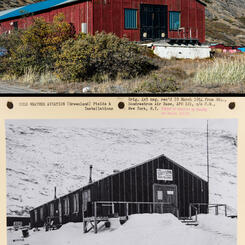

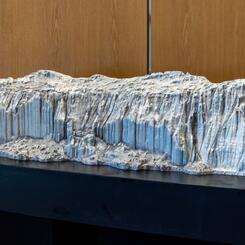

Foreign Objects: The Transformation of a Greenlandic LandscapeGreenland Ice Sheet in Midsummer (2022) Part of my project concerns "the journey of ice and water" from the ice sheet that covers 80% of Greenland and downriver 20 miles to the Kangerlussuaq Fjord from which it eventually flows into the ocean. Streams of meltwater form on the surface of the ice in midsummer. This is a natural process, but there has been an increased rate of melting since 2000 is due to climate change, and the impact is visible at the edge of the ice in Kangerlussuaq which has retreated inland about a half-mile since then.

Available for Purchase -

Foreign Objects: The Transformation of a Greenlandic Landscape

Foreign Objects: The Transformation of a Greenlandic LandscapeAirport Signpost (2021) and Andreas Lund-Drosvad with Signpost (unknown photographer, 1959) Part of my project includes locating vintage photos in archives and rephotographing the same sites. Here Kangerlussuaq’s iconic red and white signpost originally stood in front of the former civilian hotel before being relocated to the airport. In 2014 the signpost was renovated by Air Greenland, changing the flight times, adding cities, and removing the SAS company emblem from the top. Andreas “Suko” Lund-Drosvad (1899-1989) posed with the sign in 1959. He moved to Greenland from Denmark in the 1920s and established a museum in the town of Upernavik.

Available for Purchase -

Foreign Objects: The Transformation of a Greenlandic Landscape

Foreign Objects: The Transformation of a Greenlandic LandscapeMock Airplane Crash for Firefighter Training (2022). I am currently working on a photo book project exploring the remote Arctic town of Kangerlussuaq, Greenland, a former indigenous hunting ground that has been reshaped by its highly unusual geopolitical history and the impact of climate change, including as a US Cold War Air Base from 1941 to 1992. The base closed in 1992 but the town and environs are dominated by its infrastructure, including repurposed and abandoned buildings and vast quantities of obsolete equipment left behind. Not all the old military junk ends up in the junkyard. On the outskirts of town, this assemblage of an old fuel tank, barrels, ladders, and scrap lumber serves as a mock airplane crash periodically set ablaze for firefighter training.

Available for Purchase -

Foreign Objects: The Transformation of a Greenlandic Landscape

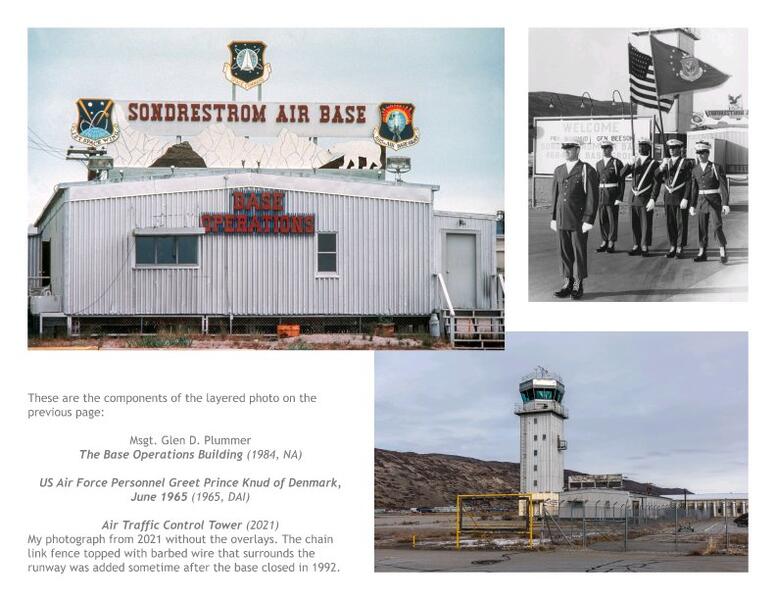

Foreign Objects: The Transformation of a Greenlandic LandscapeAir Traffic Control Tower and Former Entrance to Sondrestrom Air Base (1965, 1984 and 2021)

The air traffic control tower built for the base still serves that function today. I photographed it in 2021. Vintage photos of the airbase from Danish and US archives show that the yellow bars once held a sign welcoming visitors to Sondrestrom Air Base. On the roof of the building behind the tower was a larger sign decorated with military unit emblems and a landscape with a polar bear. I overlaid two vintage photos with the signs on mine—one of US soldiers greeting Prince Knud of Denmark in 1965, and one from 1984 of the Base Operations sign. From a long-term project about the transformation of the landscape of Kangerlussuaq, Greenland, site of a former US Air Force Base during the Cold War, which combines vintage photographs from archives with my own.

Available for Purchase

About Helen

ARTIST STATEMENT

I have long been absorbed in understanding the processes underlying patterns of growth and form in nature. My photographs and photo-based sculptures interpret landscapes in terms of the forces that shaped them: the interaction between geology, ecology, human behavior, and the built environment. Digital photography has become my principal medium for its ability to capture complex transient phenomena from different vantage points. It has… more

The Transformation of a Greenlandic Landscape: Photocollages

Like many contemporary photographers, I also have become interested in mining archives for vernacular photos — i.e. made without artistic intent, such as snapshots taken by servicemen or visiting scientists, or the straightforward documentation of facilities by Air Force photographers. Along with the narrative and descriptive captions, placing photographs from the past in dialogue with my own adds additional context to the present. This could mean, variously, recognizing what the human interventions have added to the present landscape, revealing structures that have not survived into the present, or showing built or landscape features that have since been transformed or disappeared entirely. Digital photography tools also offer me the ability to combine images made in the past with mine through transparent overlays into a single composition, to literally depict the layered accumulation from the past here, including at times the transitory presences of people who once activated the spaces, many of whom are no longer alive.

I have also included compositions I made from only my own photographs to create an image where they work together as a photocollage.

-

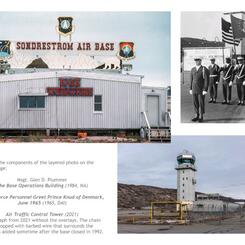

Air Traffic Control Tower, Prince Knud of Denmark’s Visit to Sondrestrom Air Base, and The Base Operations Building (Montage: 2024)

Air Traffic Control Tower, Prince Knud of Denmark’s Visit to Sondrestrom Air Base, and The Base Operations Building (Montage: 2024)The air traffic control tower — which is still in use — and the buildings behind it are featured in many vintage photos of the base. The yellow bars once held a sign welcoming visitors to Sondrestrom Air Base. On top of the building behind it was a sign with US military emblems and a landscape with a polar bear — although bears rarely venture this far south. I have overlaid portions of vintage photos of US soldiers greeting Prince Knud of Denmark (Danish Arctic Institute, 1965) and the original sign (US National Archives, 1984) over my 2021 photograph of the site.

-

Individual photographs used in previous image

Individual photographs used in previous imageThese are the components of the layered photo on the previous page: Msgt. Glen D. Plummer, The Base Operations Building (1984, National Archives); US Air Force Personnel Greet Prince Knud of Denmark, June 1965 (1965, Danish Arctic Institute); Air Traffic Control Tower (2021). My photograph from 2021 without the overlays. The chain link fence topped with barbed wire that surrounds the runway was added sometime after the base closed in 1992.

-

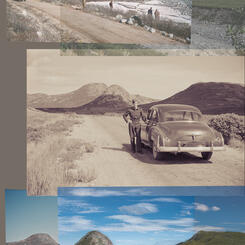

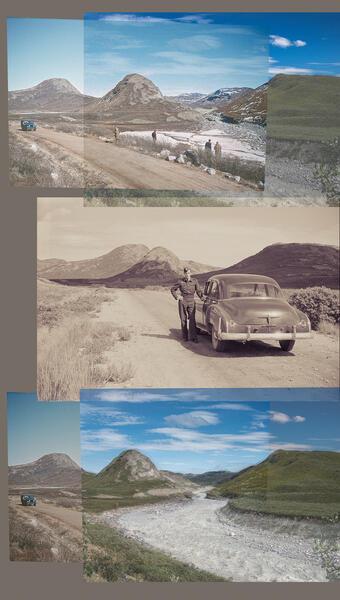

Road to Sugarloaf (Montage: 2025)

Road to Sugarloaf (Montage: 2025)Layered montage of photographs of the road east from the base toward the ice sheet, alongside the Akuliarsuup River looking toward the mountain called Sugarloaf. It combines (from top) with two photographs from the 1950s made by Danish scientists who used the base as a site from which to conduct research: a 1957 photograph by Børge Fristrup in early spring and a 1952 photograph of a serviceman with the US colonel's Chevrolet by Christian Vibe. At the bottom is featured my 2022 photograph at the height of midsummer when meltwater from the ice sheet rushes downstream.

-

Roller Drivers on the Runway (1947 and 2022)

Roller Drivers on the Runway (1947 and 2022)The left photograph in the US National Archives shows a roller driver putting the finishing touches on the US air base runway in July 1947 as part of “Project Mailbag.” 75 years later, in July 2022, I was walking on the road alongside the same runway when a Greenlandic construction worker who had just finished work for the day drove a roller past and waved.

-

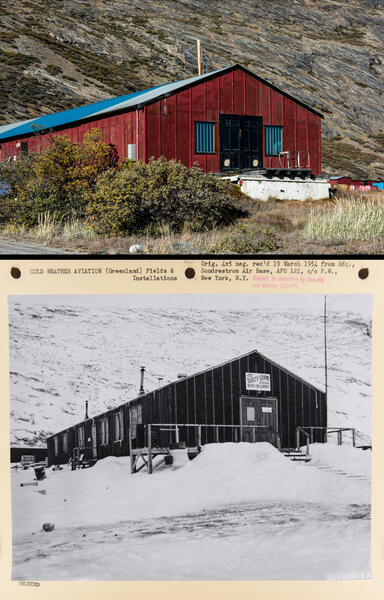

Kangerlussuaq Hostel, Former Caribou Club for Non-Commissioned Officers (Montage: 2024; Photos: 2022 and 1980s)

Kangerlussuaq Hostel, Former Caribou Club for Non-Commissioned Officers (Montage: 2024; Photos: 2022 and 1980s)(Montage: 2024; Photos: 1980s and 2022) Photograph of what is now the Kangerlussuaq Hostel, overlaid with a vintage photo by Ole Simonsen from the Danish Arctic Institute of the building when it was the Caribou Club, a social and recreation facility for non-commissioned military officers.

-

Caribou Pausing on a Rock and JATO Bottle with Antlers (Montage: 2026; Photos: 2022)

Caribou Pausing on a Rock and JATO Bottle with Antlers (Montage: 2026; Photos: 2022)A male caribou pauses on a flat rock in the hills outside town on a summer evening. Caribou are native to West Greenland and before the air base, indigenous people would travel by kayak and on foot from coastal settlements to hunt them here during the summer months. Hunting caribou is still an important part of the culture and food supply. Beside it is a montage made with a detail and full photo of a JATO rocket fuel bottle, used as a cigarette ashtray at a bus stop, where it is decorated with caribou antlers.

-

JATO Rocket Fuel Bottles (2022)

JATO Rocket Fuel Bottles (2022)Empty JATO (jet-assisted take-off) rocket fuel bottles that once provided extra thrust for take-offs for ski-equipped planes from the ice sheet are now ubiquitous outside buildings as outdoor cigarette ashtrays, another example of repurposing discarded base relics that makes Kangerlussuaq unique.

-

Kangerlussuaq Recreation Center (Montage: 2026; Photos: 1973 and 2022)

Kangerlussuaq Recreation Center (Montage: 2026; Photos: 1973 and 2022)A photograph of the Change of Command Ceremony on May 4, 1973 from the Danish Arctic Institute is overlaid onto a photograph I took in 2022 of the same room in the Kangerlussuaq Recreation Center, which then and now also served as a basketball court. The recreation center also has a well-maintained indoor pool, which for many years was the only one in the country.

-

Plywood Markers Outlining the Site of Greenland's First Airplane Runway (Montage: 2025; Photos: 2022)

Plywood Markers Outlining the Site of Greenland's First Airplane Runway (Montage: 2025; Photos: 2022)The site of Greenland's first runway, originally prepared by a University of Michigan geology expedition in 1928 for the Rockford Flyers, a pair of American aviators who never landed there. (They ran out of fuel 110 miles south and managed to arrive on foot two weeks later, when they were spotted and rescued.) The weathered plywood markers weighted with rocks are a later addition, but mark the outline of the original runway.

-

Fuel Oil Barrels Recycled as Guardrails (Montage: 2025; Photos: 2022)

Fuel Oil Barrels Recycled as Guardrails (Montage: 2025; Photos: 2022)Even though the EPA conducted a cleanup of the Sondrestrom Air Base after it closed in 1992 and removed at least 2,000 barrels, many remain, some in the junkyard, others strung with cables, painted bright colors and used as guardrails along the gravel roads outside town.

Climate Change at the Greenland Ice Sheet

I am currently working on a photo book project exploring the remote Arctic town of Kangerlussuaq, Greenland, a former indigenous hunting ground that has been reshaped by its highly unusual geopolitical history as a former US Cold War Air Force base and the impact of climate change. In 1999, Volkswagen Motors built a road to the ice cap covering 80% of Greenland for a short-lived failed project to test drive cars on ice. The effects of climate change are starkly visible at the road's end, formerly the ice sheet edge, now a long gravel slope uncovered by melting ice.

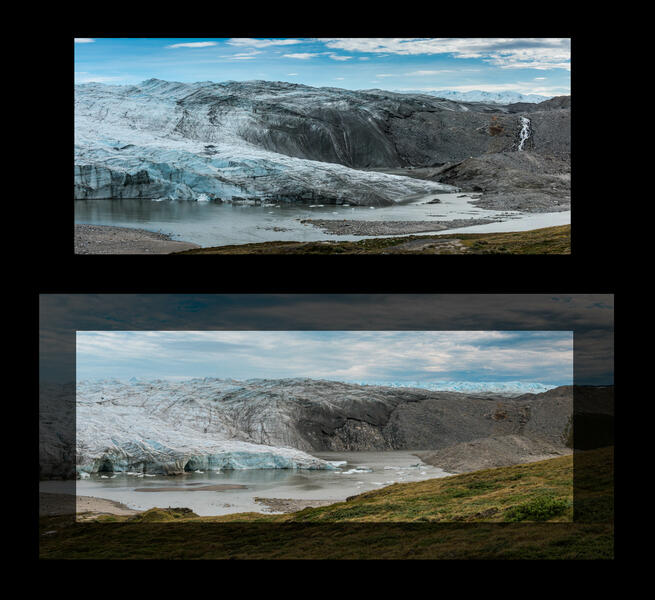

In 2023, I collaborated with the Kangerlussuaq Museum, which received funding from the US Embassy in Copenhagen to redo two rooms with a permanent exhibit of my photographs and one sculpture. One room follows "The Journey of Ice and Water" showing places along the approximately 20-mile river fed by the melting ice cap to the site of the town at mouth of the fjord. These 10 photos focus on the ice cap and glaciers that flow off of it. They include a vintage photograph from the 1950s of one of the sites, the Russell Glacier, which shows the effects of climate change when compared to my photos at that site.

-

Greenland Ice Sheet in Autumn (2021)

Greenland Ice Sheet in Autumn (2021)Standing on the ice sheet that covers 80% of Greenland in September after a few inches of snow had fallen and the ground froze. This photograph is on permanent display at the Kangerlussuaq Museum.

-

Greenland Ice Sheet, Midsummer (2022)

Greenland Ice Sheet, Midsummer (2022)Standing on the ice sheet that covers 80% of Greenland in summer when meltstreams form. Gravel blown onto the icy crust makes this image resemble a pencil drawing. This photograph is in a permanent installation at the Kangerlussuaq Museum.

-

End of the Volkswagen Ice Road (2022)

End of the Volkswagen Ice Road (2022)This photo was taken from the top of the moraine at the end of the Volkswagen road, which stretches into the distance. My back was to the ice sheet and the view of the tourists in the next photo. In 2000, when the road was completed, Volkswagen’s convoys drove onto the ice sheet directly from where I was standing. The project was abandoned by 2005 as impractical due to unanticipated ice dynamics. This coincides with the onset of increased melting of the ice sheet due to climate change beginning in 2000. The Greenland Home Rule government maintains the road as an amenity for scientists and tourists. The road's end also provides a benchmark for the effects of climate change.

-

Tour Group Walking on the Greenland Ice Sheet, Point 660

Tour Group Walking on the Greenland Ice Sheet, Point 660Buses ferry visitors to the ice sheet to witness its sublime beauty on the road built in 1999-2000 by Volkwagen Motors. In 2001 when the auto testing project was active, vehicles could drive directly onto the ice cap from the end of the road. Now visitors walk down the steep gravel hill formerly covered by the ice cap in the foreground of this photograph. As the ice sheet melts and its edge recedes inland, it also uncovers permafrost (a layer of soil that is frozen year round). This photograph is in a permanent installation at the Kangerlussuaq Museum.

-

Retreating Edge of the Greenland Ice Sheet (2022)

Retreating Edge of the Greenland Ice Sheet (2022)20 years before this photograph was taken, the ice cap that covers 80 percent of Greenland also covered the steep moraine on the left. The ice has since retreated inland. (A regional government official told me that the ice formerly covering the moraine has dropped 30 to 50 meters since then.) In July, a swiftly flowing stream filled by meltwater from the ice cap divided the ice cap edge from the moraine.

-

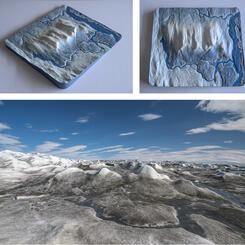

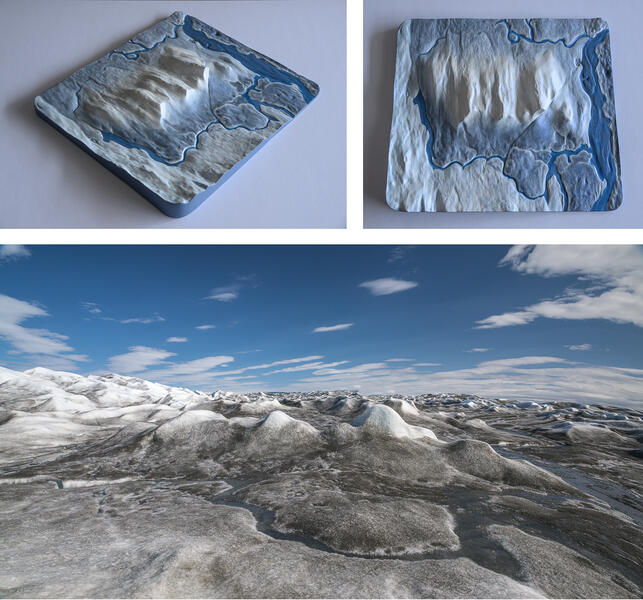

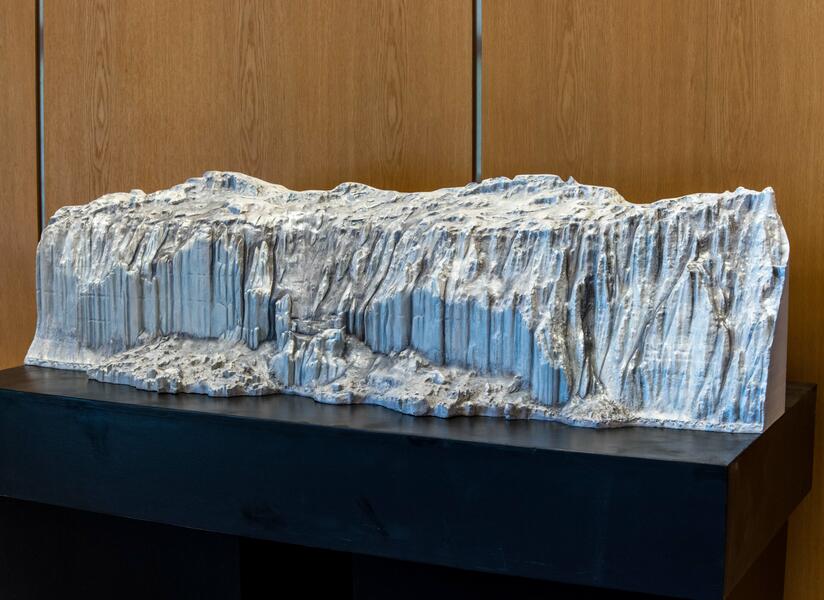

Portion of the Greenland Ice Sheet in Summer: Sculpture with Source Photo (2023)

Portion of the Greenland Ice Sheet in Summer: Sculpture with Source Photo (2023)This sculpture measuring 17.25 x 15.25 x 1.75 inches was made from a 3D scan of a small section of the ice sheet for the permanent installation at the Kangerlussuaq Museum. The dark blue represents the streams of water that had formed under the summer sun. To make the sculpture, first a series of photographs of the scene from different angles were processed into a 3D file using photogrammetry software. After editing the file with 3D modeling software, it was carved in high density urethane foam by CNC router, a machine that can read 3D files. Since the ice is constantly changing — and melting — this is a permanent record of a temporary form. One of the source photos from which this sculpture was made is also shown.

-

Permafrost Cracks at the Ice Sheet Edge (2022)

Permafrost Cracks at the Ice Sheet Edge (2022)This area was covered by the Greenland ice cap 20 years ago. As the ice cap edge melts and recedes inland, it exposes the permafrost layer (frozen soil) to the sun, opening ice-walled cracks that grow deeper and more numerous each year once the soil is exposed to the sun. In midsummer, streams run through the cracks as the permafrost melts, another contributor to downstream impacts of climate change in Kangerlussuaq and ultimately, global sea level rise.

-

The Russell Glacier (2022 and 1955)

The Russell Glacier (2022 and 1955)The Russell Glacier, named by the American geologist William Herbert Hobbs for a University of Michigan colleague in the late 1920s, is an outlet glacier from the Greenland ice sheet. Its front is located 25 km east of Kangerlussuaq and 7 km west of the end of the Volkswagen road where the previous photos were taken. Here my panoramic view is paired with a photograph below it taken by Danish glaciologist Børge Fristrup in 1955 (collection Danish Arctic Institute). The glacier has lowered in height and lost ice along the river noticeably since then. This pair of photographs is in the permanent installation at the Kangerlussuaq Museum.

-

Russell Glacier from the Top of the Waterfall (2023)

Russell Glacier from the Top of the Waterfall (2023)During the summer a torrent of meltwater from the ice sheet tumbles down a waterfall at the north end of the glacier carving out and collapsing the edge on its downstream journey to Kangerlussuaq Fjord. This spot is hidden by the hill on the left in the previous photo.

Available for Purchase -

Guide Photographing Tourists on the Greenland Ice Sheet (2023)

Guide Photographing Tourists on the Greenland Ice Sheet (2023)A local tour guide photographs a young Danish couple visiting Kangerlussuaq on holiday during a private tour to the ice sheet in mid September when it was freshly covered with snow. Tourism became the town’s main economic driver, facilitated by the frequent international flights, infrastructure left behind by the US Air Force, and the road to the ice sheet left by Volkswagen.

The Journey of Meltwater from the Greenland Ice Sheet

Climate change photography of glaciers tend to focus on the recession of glaciers and then-and-now comparisons between earlier photographs of these sites. Far less attention is given to the downstream effects of the increased outflow of meltwater, which eventually makes its way downstream and eventually out into the ocean, contributing to sea rise affecting coastlines around the world, including close to home, places like Annapolis. The next set of photographs follow the journey of meltwater from the Greenland Ice Sheet to the Kangerlussuaq Fjord. Some of these are in the permanent installation at the Kangerlussuaq Museum that I installed in 2023. See the prior portfolio: Climate Change at the Greenland Ice Sheet for more information.

-

Reindeer Glacier Ice Loss Between 2018 and 2022

Reindeer Glacier Ice Loss Between 2018 and 2022Photographs taken on my first visit to Kangerlussuaq (a one-day visit as part of a tour in 2018, top) and when I returned four years later (bottom) show the extent of the ice loss over that period, in terms of the overall elevation of the ice, the portion extending into the river, and the portion over the dark gravel hill on the right. "Reindeer Glacier" is the local nickname for this portion of the ice cap. These photographs are part of the permanent installation at the Kangerlussuaq Museum.

-

Waterfall Along Akuliarusiarsuup Kuua (2022)

Waterfall Along Akuliarusiarsuup Kuua (2022)A powerful waterfall churns with meltwater several miles downstream from the Greenland ice cap in midsummer. This photograph is in the permanent installation at the Kangerlussuaq Museum.

-

Rocket Launch Platforms Along the River (1974 and 2022)

Rocket Launch Platforms Along the River (1974 and 2022)In the 1970s, five concrete rockt launch pads for meteorological research were installed east of the base along the shore of the Akuliarusiarsuup Kuua river, as seen in a 1974 photo (by Jørgen Taagholt) in the collection of the Danish Arctic Institute (top left). Increased water flow from the melting ice sheet have heavily eroded the banks, leading to the collapse of all but one of the original platforms into the river. As of 2020, there were still two platforms on land, but on a visit to the site in 2022, only one remained (bottom left); the other was jutting from the river (right).

-

Kangerlussuaq Panorama from Black Ridge (2022)

Kangerlussuaq Panorama from Black Ridge (2022)A panorama of the town from the top of Black Ridge (elev. 360 feet), a hill overlooking the confluence of the river from the ice cap and the fjord leading out to sea (located where the bridge is). Most of the buildings were originally built by the American military which also blasted two channels beneath where the bridge is now so the area around the shore wouldn't flood during the summer melt season. The sites shown in the next 6 photographs can all be seen from right to left in this panorama, following the direction of the river flow. This photograph is part of the permanent installation at the Kangerlussuaq Museum.

-

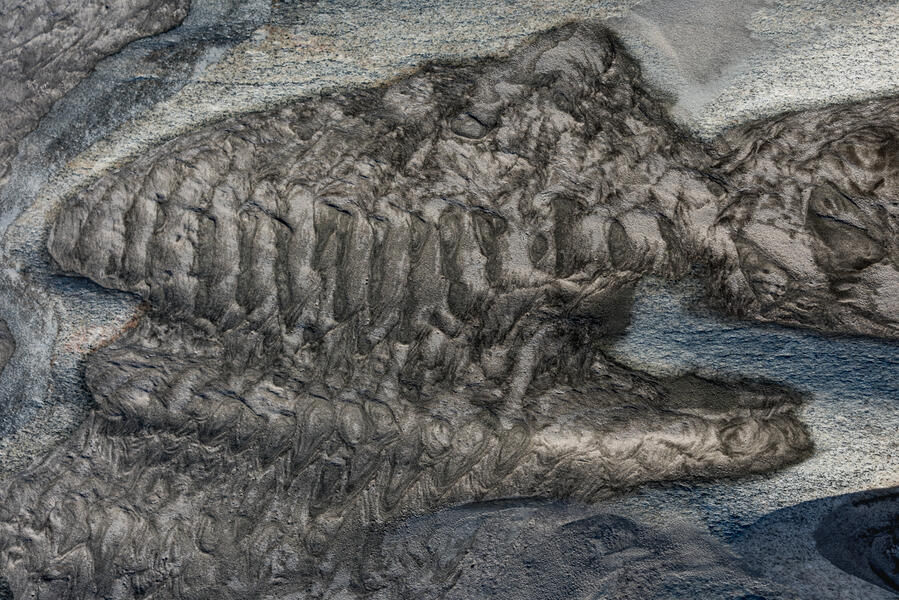

Glacial Silt, Riverbank (2022)

Glacial Silt, Riverbank (2022)A close-up of the wave-like patterns of silt on the rocks just around the bend from the town bridge where the river empties into the Kangerlussuaq Fjord. In the summer the rivers that run between the ice sheet and the Kangerlussuaq Fjord are fed by the melting of the Greenland ice sheet flowing off the Russell Glacier mixed with fine glacial silt. As one scientist puts it, “By the time it gets to Kangerlussuaq and passes under the town’s bridge, it’s essentially a rock, soil, and sand smoothie.

-

Bridge Over the Fjord with Jack T. Perry Memorial Plaque (2021)

Bridge Over the Fjord with Jack T. Perry Memorial Plaque (2021)Shortly before he was scheduled to return home from his deployment in August 1976, American serviceman Jack T. Perry and two friends embarked on a river rafting trip from the ice sheet in an inflatable boat. Suddenly they heard the roar of a waterfall ahead. His friends jumped out and swam to shore, but he remained in the boat, which was swept backwards over the edge. Search and rescue efforts failed to locate him. His body remained missing for 10 years, until two hotel workers noticed a combat boot sticking up out of the permafrost, seven kilometers downstream from the waterfall. A plaque was mounted on the bridge in his memory.

-

Kangerlussuaq Bridge from Above (2022)

Kangerlussuaq Bridge from Above (2022)The American military blasted two channels beneath where the bridge is now so the area around the shore wouldn't flood during the summer melt season. It has also altered the ecology so that not only does more silt flows into the fjord, but a jetty was built a short distance downstream to redirect the powerful surge of water that was eroding the banks near the airport runway. This photograph is on a two-page spread in the book The New Geologic Epoch (ecoartspace, 2023).

-

Glacial Silt, Kangerlussuaq Fjord (2021)

Glacial Silt, Kangerlussuaq Fjord (2021)Every summer, the soupy mix of melted ice and fine glacial silt from the Greenland ice sheet settles in the fjord after passing beneath the town bridge. Here, as autumn arrives, the water level decreases, revealing semi-frozen mud — and quicksand. This photograph is part of the permanent installation at the Kangerlussuaq Museum.

-

Glacial Silt Deposited Beneath the Bridge (2021)

Glacial Silt Deposited Beneath the Bridge (2021)In fall, after the water had receded, I could walk onto the rocks beneath the bridge. Here is a close-up of the wave-like patterns of semi-frozen silt on the rocks where Qinnguata Kuussua (also known as Watson River) empties into the Kangerlussuaq Fjord after passing through a channel in the rock blasted by the American military. The river is fed by melting of the Greenland ice cap flowing off the Russell Glacier, which, as shown in a previous photo, in the summer months is milky with fine glacial silt.

-

Rocks and Rebar, Kangerlussuaq Fjord (2021)

Rocks and Rebar, Kangerlussuaq Fjord (2021)As the water flow receded in fall, I took this view from the bridge looking down on the eroded rocks below, where the river flowing from the Greenland ice cap some 20 miles away empties into the fjord. A piece of rebar is embedded in the rock, possibly from one of the earlier bridges this one replaced.

Cold War Legacies in a Greenlandic Landscape

The evolution of Kangerlussuaq from transient indigenous hunting ground to the village it is today came about through events far from Greenland’s shores. As Hitler’s army seized a series of European countries in 1940 — including Denmark, which had sovereignty over Greenland — leaders in the United States realized that they would not be able to remain neutral for long to support their European allies and protect the North Atlantic. The US rushed to protect Greenland from Nazi incursion and began building bases in 1941 including here, on the advice of a University Michigan geologist William Herbert Hobbs who predicted the relatively fog free weather this far inland would provide the best aviation conditions in Greenland. During World War II the base served as a stopover for fighter jets being sent to the European front. When the Soviet Union turned from World War II ally to nuclear-enabled adversary, the base became part of the Cold War defense system monitoring the skies for incoming Soviet missiles. The base was closed in 1992 after the fall of the USSR and changes to technology reduced the need for a physical presence. The town was then turned over to the Greenland Home Rule Government and having at the time the only runway that could accommodate large jets, became Greenland's international civilian aviation hub.

-

Base Commanders Office, Kangerlussuaq Museum (2021)In 1992, the American air base commander turned over the keys to the buildings to the local airport authorities and left the contents intact at their request, including his US military issue parka and the trophy musk ox head on the wall. It is preserved today in the town museum.

Base Commanders Office, Kangerlussuaq Museum (2021)In 1992, the American air base commander turned over the keys to the buildings to the local airport authorities and left the contents intact at their request, including his US military issue parka and the trophy musk ox head on the wall. It is preserved today in the town museum. -

Andreas Lund-Drosvad with Signpost (1959) (Danish Arctic Institute Collection) Signpost, Kangerlussuaq Airport (2021)

Andreas Lund-Drosvad with Signpost (1959) (Danish Arctic Institute Collection) Signpost, Kangerlussuaq Airport (2021)The iconic red and white signpost originally stood in front of the civilian hotel before being relocated to the airport. In 2014 it was renovated by Air Greenland, changing the flight times, adding cities, and removing the SAS company emblem from the top. Andreas “Suko” Lund-Drosvad (1899-1989), a Dane who lived in Upernavik, Greenland, and founded a museum there, posed with the sign in 1959. This pair of photographs is in the permanent installation I installed in the Kangerlussuaq Museum in 2023.

-

Sondrestrom Offshore Transit Home (2021)

Sondrestrom Offshore Transit Home (2021)The former Offshore Transit Home of the Sondrestrom Air Base is one of many abandoned military buildings I photographed. This one is in the part of town known as Old Camp, where barracks for Danish troops and facilities for the entire base were located. Dozens of disconnected telephone poles like the ones here are found throughout the base. (They were shipped here by the US military from outside Greenland which has no native trees that grow more than a few feet high.) They are gradually being cut down and added to a huge pile in the town junkyard.

-

The Dirty Shame Saloon 2021 and 1954

The Dirty Shame Saloon 2021 and 1954Part of my project involves rephotographing sites in old photos of the air base as they look today. My 2021 photograph of an abandoned building is shown here with a rephotographed 1954 mounted print from the US National Archives when it was The Dirty Shame Saloon.

-

"Mickey Mouse" Decommissioned Radar Dishes (2022)Erected over 60 years ago, this pair of decommissioned Cold War era radar dishes and radio terminal building left behind by US military have become a landmark locals refer to as "Mickey Mouse," as in, "Follow the road past Mickey Mouse..." Before the dish technology became obsolete in the late 1980s, they served as relay antennae channeling all communications to and from scattered radar sites for the Distant Early Warning missile defense system that stretched across the Arctic from Greenland to Alaska. I have found photos of them from 1961 in the US National Archives.

"Mickey Mouse" Decommissioned Radar Dishes (2022)Erected over 60 years ago, this pair of decommissioned Cold War era radar dishes and radio terminal building left behind by US military have become a landmark locals refer to as "Mickey Mouse," as in, "Follow the road past Mickey Mouse..." Before the dish technology became obsolete in the late 1980s, they served as relay antennae channeling all communications to and from scattered radar sites for the Distant Early Warning missile defense system that stretched across the Arctic from Greenland to Alaska. I have found photos of them from 1961 in the US National Archives. -

Mock Airplane for Firefighter Training (2022)

Mock Airplane for Firefighter Training (2022)Base leftovers give Kangerlussuaq its quirky appearance. Here, an old fuel tank and oil drums from the former American air base have been repurposed into a mockup of an airplane crash periodically set ablaze for firefighter training.

-

2021-0923-155.jpg

2021-0923-155.jpgHobbs first landed at this beach or the adjoining shoreline. The rocky slope is covered with graffiti dating back as far as 1954 including names of US military units — the first tip off to a visitor arriving by ship that this is not a typical Greenlandic town.

-

2021-0923-148.jpg

2021-0923-148.jpgAmong the military debris left behind is this decaying barge is anchored in the harbor, with half its port side hull gone. It is among the many massive relics of the air base that are too big to be moved and too expensive to haul away.

-

Abandoned Generator Station Interior, Lake Jean Global Communications Site (2022)

Abandoned Generator Station Interior, Lake Jean Global Communications Site (2022)A building atop a hill near Hobbs’ former weather station contains three large diesel generators, their interiors still coated with inky grease. They once powered the USAF global communication station and a 450-meter mast said to be the tallest man-made structure in the world at the time, which communicated with planes throughout the North Atlantic after the mast was erected in 1953. The mast was dismantled in 1969, with parts of it moved to an island near Nuuk, Greenland, but its concrete supports remain on the hill.

-

US Air Force Planes on Runway (2022)

US Air Force Planes on Runway (2022)Four US Air Force planes parked on the Kangerlussuaq Airport runway in 2022. Although Sondrestrom Air Base closed in 1992, a New York Air National Guard unit has maintained an outpost there to train polar pilots for Arctic and Antarctic missions. They also transport scientists and supplies to Summit Station, a year-round research facility operated by the US National Science Foundation in the center of the ice sheet, as well as to smaller temporary field camps during the summer research season.

Walking in Greenland: Every Landscape Tells a Story

In creating this portrait of Kangerlussuaq, by virtue of my roots in fine art photography and its history and contemporary concerns, I am uniting the environmental geography approach with the aesthetic and creative possibilities of the medium to place you in the space and focus your attention as an observer, while giving you the backstory to “read” the landscape and understand something of the process by which it came to be. Within these pages you will find sweeping views and intimate poetic details, human ingenuity as well as human carelessness, awe and grandeur as well as humor — sometimes with more than one of these existing within the same image.

-

North Shore of Kangerlussuaq Fjord, Looking West (2018)

North Shore of Kangerlussuaq Fjord, Looking West (2018)“In choosing this fjord for...our Greenland weather station it has been necessary to assume a considerable risk, for no maps exist which tell us anything of the country once the fjord has been left behind.”

—University of Michigan geologist William Herbert Hobbs, on entering the fjord in 1927

-

Autumn Foliage and "The Ayatollah" (2023)

Autumn Foliage and "The Ayatollah" (2023)Tundra plants turned red and gold in September cling to a smooth rock formation on Black Ridge. In the 1980s Americans and Danes on the air base referred to the black and white pattern lower right as “The Ayatollah” because they thought it resembled a bearded man with a white turban, like Ayatollah Khomeini, leader of Iran. The name has stuck.

-

Female Musk Ox (2022)

Female Musk Ox (2022)The thousands of musk oxen (Ovibos moschatus) roaming the hills surrounding Kangerlussuaq today are descended from just 27 calves brought here from East Greenland in the 1960s in an effort to perpetuate the species and establish them in West Greenland. This musk ox was with a herd grazing in the hills east of Lake Ferguson. It was a long day of hiking on spongy steep terrain until we quietly managed to creep around a small hill and hide behind a rock about 25 meters away. For a little over 15 minutes they tolerated our presence. This photograph is in the permanent installation at the Kangerlussuaq Museum.

-

Roadside Memorial to Willy the Musk Ox (2023)

Roadside Memorial to Willy the Musk Ox (2023)Today, the story of Willy the Muskox has endured long past the time where anyone still living there has firsthand memories of him. One of the original 27 calves released south of the fjord, he took to crossing the bridge and wandering the base, where he became a sort of mascot and acquired his nickname. However, as Willy matured, he periodically became aggressive — often incited by soldiers for their own amusement. Attempts to relocate him failed, for he always returned. One day, the base commander ordered him shot, elevating him to folk hero status.

-

Arctic Hare, Old Camp, Kangerlussuaq (2022)

Arctic Hare, Old Camp, Kangerlussuaq (2022)An Arctic hare (Lepus arcticus) springs from the bushes in the section known as Old Camp, which housed Danish troops and civilian contractors. Its summer coat of gray fur will turn white as winter approaches. This photograph is in the permanent installation at the Kangerlussuaq Museum.

-

Sondrestrom Incoherent Radiation Radar (2022)

Sondrestrom Incoherent Radiation Radar (2022)Looking up at the intricate engineering of the Sondrestrom Incoherent Scatter Radar dish, built in 1971 for atmospheric research in Alaska, moved to Kangerlussuaq, Greenland in 1982, where it has stood unused since 2018. It was originally moved there because there was a hole in the ionosphere just above that area that makes it easier to gather information from space. In 2023, the surrounding buildings where science personnel lived and worked were torn down to make way for a University of New Brunswick research group that is planning to reactivate it. This photograph is in the permanent installation at the Kangerlussuaq Museum with a vintage 1984 photo of the radar dish complex, known locally as Kellyville after John Kelly, the scientist who initiated the project.

-

Remnants of Tree Planting Experiment (2023)

Remnants of Tree Planting Experiment (2023)Scattered conifers and birch trees near the road outside of town are the survivors of an effort led by a Danish botanist to introduce trees native to other North American locations to sites in Greenland; this was largely unsuccessful in Kangerlussuaq. The trees’ slender trunks and relatively small size bely the fact that most are 40 to 50 years old (although a few may have produced cones that later took root). In 2023 someone had whimsically hung Christmas tree ornaments on one. Hidden in its branches is a tag from the study.

-

Hilltop Beacons (2021)

Hilltop Beacons (2021)A pair of painted rocks on a hillside above the Kangerlussuaq Harbor served as aircraft beacons meant to be visible from the air to approaching planes. In the 1950s, the American servicemen referred to them by the crass term “the tits of Marilyn Monroe.”

-

Cottongrass (2022)

Cottongrass (2022)The fine white hairy strands of cottongrass sprout besides streams and drainage ditches in the Arctic summer.

-

Arctic Bluebells (2018)

Arctic Bluebells (2018)Tundra wildflowers that grow during the brief Arctic summer, which I photographed on my first 24-hour visit to Kangerlussuaq that inspired this project.

Kangerlussuaq: The Making of a Community

After the closure of Sondrestrom Air Base, it evolved into civilian hometown renamed Kangerlussuaq after the Inuit name for the fjord. Unlike other Greenlandic settlements with roots going back generations, the community was so transient it did not even have a proper cemetery until 2012. Possessing Greenland’s only practical facility for landing large commercial jets, Kangerlussuaq became the country’s international hub, through which all travelers abroad passed before transferring to connecting flights on smaller planes to their final destinations. The village gradually evolved into a tight-knit community of Inuit and expatriate Danes attracted by the wide-open mountainous countryside, small-town camaraderie, and employment opportunities at the airport or in the evolving tourist economy that enabled a comfortable standard of living.A complex of former base buildings houses a constant flow of international scientists during the summer months, with transportation to remote science stations provided by a small New York Air National Guard outpost. Kangerlussuaq’s atypical appearance compared to other Greenlandic towns is the result of the ubiquitous buildings and infrastructure that remain from its military past. Some buildings have been renovated and repurposed, others are empty and dilapidated. However, as much useless material that decays in place or ends up hauled to the town junkyard, I have also documented how people have put some of it to ingenious new use.

-

Kangerlussuaq Airport Departure Lounge (2021)

Kangerlussuaq Airport Departure Lounge (2021)Small bronze sculptures by Heike Arndt, a German artist with a studio in Denmark, decorate the departure lunge. Kangerlussuaq's status as Greenland's international air hub became the engine of the local economy in 1992, although during 2025, Air Greenland moved its hub to a newly expanded airport in the capital, Nuuk, which has had a major impact on the community. About 30% of the citizens left, but those who remain have met the challenges with passion, pride and determination to find a way forward in a place they see as home.

-

Cyclist Passing Airport Terminal (2022)

Cyclist Passing Airport Terminal (2022)After 1992, Kangerlussuaq transitioned from military installation to Greenland’s international civilian air hub, with regular flights to and from Copenhagen via Air Greenland and a steady stream of connecting flights to other Greenlandic airports throughout the day. The airport and businesses serving travelers dominated the economy until late 2024 when the hub was moved to Nuuk.

-

Kangerlussuaq Junkyard (2022)

Kangerlussuaq Junkyard (2022)The Kangerlussuaq junkyard is an astonishing place, a semi-organized conglomeration of the discarded appliances and household items you’d see in any town dump alongside decades-old relics of the US military base closed 30 years ago: obsolete vehicles and machinery; dozens of telephone poles, empty oil drums, and fuel tanks; and stacks of scrap metal.

-

Utility Poles, Kangerlussuaq Junkyard (2022)

Utility Poles, Kangerlussuaq Junkyard (2022)Disconnected wood utility poles, wires cut, still line long stretches of road, remnants of the former base. Gradually they are being cut down and hauled to the junkyard, where they are piled like oversized Lincoln Logs jumped from a box. Greenland largely lacks waste disposal and recycling facilities, so most of the base infrastructure remains.

-

Kangerlussuaq Cemetery from Black Ridge (2021)

Kangerlussuaq Cemetery from Black Ridge (2021)Before the American Air Base was established in 1941, Kangerlussuaq was an annual hunting ground for indigenous Greenlanders who lived on the coast some 80 to 120 miles away, but not a place with permanent structures that they identified as home. The establishment of the town cemetery in 2012 represented a shift. Surrounded by a white picket fence typical in Arctic villages in Greenland and Canada, as of 11 years later it had just nine graves decorated with artificial flowers, framed photos, lanterns, and other objects bordered by stones. The nearby dark circle was the former site of an air base fuel tank; beyond is an expanse of gravel and glacial silt dubbed "Dust City" during base days and still called that. Photographed from Black Ridge, a hill approximately 300 feet in elevation.

-

Kangerlussuaq Cemetery (2022)

Kangerlussuaq Cemetery (2022)The graves are marked with white wooden crosses with metal plates bearing names of the deceased. Most are decorated with artificial flowers, framed photos, lanterns, and other objects, bordered by a low fence or stones.

-

Stone Sorter, "Dust City" (2022)

Stone Sorter, "Dust City" (2022)Airmen called the broad sandy riverbank just west of town "Dust City." This vintage stone sorter and two other nearby pieces of equipment were used by the base — and still sometimes today — for sifting gravel for road repair.

-

Polar Bear Shot Near Town, Kangerlussuaq Museum (2021)

Polar Bear Shot Near Town, Kangerlussuaq Museum (2021)Polar bears rarely venture as far south as Kangerlussuaq. In 1998, this bear was spotted a couple of miles from the settlement, considered dangerous, and shot. The taxidermied skin was mounted on the wall with photographs taken the day it was killed.

-

Young Greenland Dogs (2022)

Young Greenland Dogs (2022)Residents’ sled dogs, a breed known as the Greenland dog, are not house pets, but are kept year-round in adjoining fenced outdoor yards on the outskirts of town, as is typical of Arctic villages. This pair were interacting playfully.

-

Qiviut Workshop (2021)

Qiviut Workshop (2021)Muskoxen have become part of the local Inuit hunting culture Evald Minik Thybo works as a private tour guide. During the winter months of 24-hour darkness when tourism slows, he operates a small workshop to produce qiviut— the soft underwool beneath the longer outer wool of the muskox that is highly prized for its softness. A young man who worked for him explained to me that harvesting the wool is a laborious and strenuous process in which the hides are draped over large rubber-covered cylinders and combed with wire brushes. Evald sends the raw wool (center) to Germany to be spun into yarn (top), which he then takes to Nuuk, to sell.

Walking in Antarctica: Sea Ice Formations

Walking in Antarctica consists of photographs, sculptures from 3D scans of geological formations, and a first-person audio tour, resulting from a seven-week residency in Antarctica in 2015 through the National Science Foundation Antarctic Artists and Writers Program.

The Erebus ice tongue is the end of a glacier that extends onto the sea ice on McMurdo Sound. A small opening in the tongue leads to an ice cave containing unusual and fragile ice crystal structures. It is accessible only a few weeks a year, in the company of a trained mountaineer from the US Antarctic Program, and I was extremely fortunate to visit it twice during my residency in late November and on December 1, 2015, first with a group and then with only myself the mountaineer. Shortly after that, the cave was closed for the season.

The crystals are lit by a lamp we brought inside. You enter the first chamber by sliding through a small opening and down a slight incline on your stomach. Some light filters in through the entrance. Further inside it is pitch black. I found that bouncing lights off the walls or backlighting the features brought them to life in a way that flash photography did not, so I directed the mountaineer to aim the light in different places as I took photographs.

Some of these photos were featured in an article on the Erebus Glacier ice tongue cave on the adventure travel web site AtlasObscura.com in early 2016. Two of them have also been enlarged to 7 x 10 feet and will be installed as part of a series of exhibitions by Maryland artists at BWI Marshall International Airport between June 2017 and June 2018. One was installed in a year-long outdoor exhibition of international artists at the Palacio de las Aguas, Buenos Aires, Argentina, that opened in 2023.

The sea ice pressure ridges were on different sections of McMurdo Sound. One was near New Harbor, accessed by a one-hour snowmobile ride from the biology dive camp where I spent a few days in the field. The other pressure ridge I photographed was at Scott Base, operated by the New Zealand Antarctic Program. Three months later, the Scott Base pressure ridges collapsed into the ocean and floated out to sea.

-

Cloudburst, Erebus Ice Tongue Cave, AntarcticaCloudburst, Erebus Ice Tongue Cave, Antarctica (2015), archival pigment print, 26.75 x 40 inches. Crystals hang from an interior ceiling just inside the cave entrance. The Erebus ice tongue is the end of a glacier that extends onto the sea ice on McMurdo Sound. A small opening in the tongue leads to an ice cave containing unusual and fragile ice crystal structures. It is accessible only a few weeks a year. Further inside, it is pitch dark, but just inside the opening, the ceiling had a blue glow, illuminated by sunlight filtering through the ice.

Cloudburst, Erebus Ice Tongue Cave, AntarcticaCloudburst, Erebus Ice Tongue Cave, Antarctica (2015), archival pigment print, 26.75 x 40 inches. Crystals hang from an interior ceiling just inside the cave entrance. The Erebus ice tongue is the end of a glacier that extends onto the sea ice on McMurdo Sound. A small opening in the tongue leads to an ice cave containing unusual and fragile ice crystal structures. It is accessible only a few weeks a year. Further inside, it is pitch dark, but just inside the opening, the ceiling had a blue glow, illuminated by sunlight filtering through the ice. -

Fractal Arch, Erebus Glacier Ice Tongue Cave(2015) photograph. I went in the ice cave with a mountaineer. When I had him bounce light or backlight the features it brought out a world of intricate, layered fractal patterns.

Fractal Arch, Erebus Glacier Ice Tongue Cave(2015) photograph. I went in the ice cave with a mountaineer. When I had him bounce light or backlight the features it brought out a world of intricate, layered fractal patterns. -

Gothic Ice, Backlit, Erebus Glacier Ice Tongue Cave(2015) photograph. I went in the ice cave with a mountaineer. When I had him bounce light or backlight the features it brought out a world of intricate, layered fractal patterns.

Gothic Ice, Backlit, Erebus Glacier Ice Tongue Cave(2015) photograph. I went in the ice cave with a mountaineer. When I had him bounce light or backlight the features it brought out a world of intricate, layered fractal patterns. -

"Stalactites," Erebus Glacier Ice Tongue Cave(2015) photograph. I went in the ice cave with a mountaineer. When I had him bounce light or backlight the features it brought out a world of intricate, layered fractal patterns.

"Stalactites," Erebus Glacier Ice Tongue Cave(2015) photograph. I went in the ice cave with a mountaineer. When I had him bounce light or backlight the features it brought out a world of intricate, layered fractal patterns. -

Blue Fractal, Erebus Glacier Ice Tongue Cave(2015) photograph. I went in the ice cave with a mountaineer. When I had him bounce light or backlight the features it brought out a world of intricate, layered fractal patterns.

Blue Fractal, Erebus Glacier Ice Tongue Cave(2015) photograph. I went in the ice cave with a mountaineer. When I had him bounce light or backlight the features it brought out a world of intricate, layered fractal patterns. -

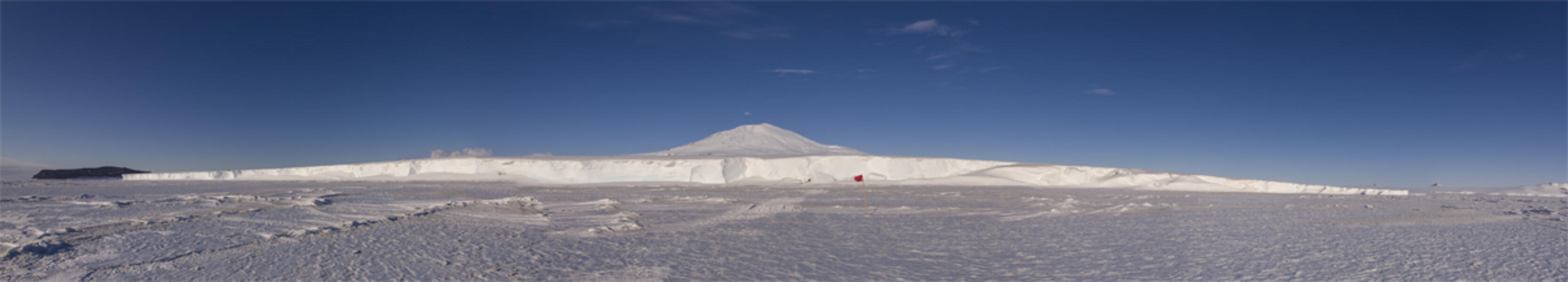

Erebus Ice Tongue Panorama, AntarcticaErebus Ice Tongue, Antarctica (2015) photograph. Photographed from the sea ice looking toward the entrance to the Erebus Ice Tongue cave is marked by a flagged path, roughly in the center of this panorama. In the background is Mt. Erebus, elevation 12,500 ft., the southernmost active volcano.

Erebus Ice Tongue Panorama, AntarcticaErebus Ice Tongue, Antarctica (2015) photograph. Photographed from the sea ice looking toward the entrance to the Erebus Ice Tongue cave is marked by a flagged path, roughly in the center of this panorama. In the background is Mt. Erebus, elevation 12,500 ft., the southernmost active volcano. -

Scott Base Pressure Ridge, AntarcticaScott Base Pressure Ridge, Antarctica (2015), photograph, 15 x 22.375 inches. This photo was taken from a hill overlooking the Scott Base pressure ridge. In the distance, on an ice shelf 7 miles away, you can barely make out the planes and buildings of the Williams Airfield, which serves the US and New Zealand bases.

Scott Base Pressure Ridge, AntarcticaScott Base Pressure Ridge, Antarctica (2015), photograph, 15 x 22.375 inches. This photo was taken from a hill overlooking the Scott Base pressure ridge. In the distance, on an ice shelf 7 miles away, you can barely make out the planes and buildings of the Williams Airfield, which serves the US and New Zealand bases. -

Scott Base Pressure Ridge, AntarcticaIcicles, Scott Base Pressure Ridge, Antarctica (2015) photograph, 15.25 x 22.375 inches. Close up of the pressure ridge, showing cantilevered ice pushed by tidal forces beneath the six-foot layer of sea ice. In the Antarctic summer, temperatures sometimes warmed to slightly above freezing, and the ice would melt and refreeze.

Scott Base Pressure Ridge, AntarcticaIcicles, Scott Base Pressure Ridge, Antarctica (2015) photograph, 15.25 x 22.375 inches. Close up of the pressure ridge, showing cantilevered ice pushed by tidal forces beneath the six-foot layer of sea ice. In the Antarctic summer, temperatures sometimes warmed to slightly above freezing, and the ice would melt and refreeze. -

Pressure Ridge Beneath the Double Curtain Glacier, AntarcticaPressure Ridge Beneath the Double Curtain Glacier, Antarctica (2015) photograph, 26.5 x 40 inches. The pressure ridges beneath the Double Curtain Glacier are seldom visited, as they are only accessible by an hour-long trip via snowmobile from the small New Harbor field camp, where I spent four days. This view overlooks the ridge, the sea ice, and the toe of the Ferrar Glacier in the distance.

Pressure Ridge Beneath the Double Curtain Glacier, AntarcticaPressure Ridge Beneath the Double Curtain Glacier, Antarctica (2015) photograph, 26.5 x 40 inches. The pressure ridges beneath the Double Curtain Glacier are seldom visited, as they are only accessible by an hour-long trip via snowmobile from the small New Harbor field camp, where I spent four days. This view overlooks the ridge, the sea ice, and the toe of the Ferrar Glacier in the distance. -

Rectangular Sea Ice, McMurdo Sound, AntarcticaRectangular Sea Ice, McMurdo Sound, Antarctica (2015), photograph, 12 x 18 inches. Photographed from a helicopter in mid-December, the surface of the sound has started to melt during the Antarctic summer, forming remarkably regular rectangular chunks surrounded by blue meltwater. In the distance are the Kukri Hills. The helicopter antennae is in the right foreground. This photograph is on view at the New York Hall of Science through February 2018.

Rectangular Sea Ice, McMurdo Sound, AntarcticaRectangular Sea Ice, McMurdo Sound, Antarctica (2015), photograph, 12 x 18 inches. Photographed from a helicopter in mid-December, the surface of the sound has started to melt during the Antarctic summer, forming remarkably regular rectangular chunks surrounded by blue meltwater. In the distance are the Kukri Hills. The helicopter antennae is in the right foreground. This photograph is on view at the New York Hall of Science through February 2018.

Walking in Antarctica: Antarctic Lake Ice

Walking in Antarctica consists of photographs, sculptures from 3D scans of geological formations, and a first-person audio tour, resulting from a seven-week residency in Antarctica in 2015 through the National Science Foundation Antarctic Artists and Writers Program.

Photographs of the unusual ice formations found in freshwater Antarctic lakes, which are fed by glaciers. These photographs were taken at Cape Royds and at Lake Hoare in the McMurdo Dry Valleys. Both areas are only visited by science teams and personnel supporting them. The Dry Valleys is a fragile environment and requires special permission to visit. I spent a week there, including five days at Lake Hoare, as a grantee of the National Science Foundation Antarctic Artists and Writers Program. My project was to photograph ice and geological formations in order to produce both archival pigment prints and three-dimensional artworks.

-

Skua, Lake Hoare, AntarcticaSkua, Lake Hoare, Antarctica (2015), photograph, 17 x 22.375 inches. This ice formation reminded me of a skua, a gull-like bird that was the only wildlife I saw during my stay in Antarctica, aside from seals and penguins.

Skua, Lake Hoare, AntarcticaSkua, Lake Hoare, Antarctica (2015), photograph, 17 x 22.375 inches. This ice formation reminded me of a skua, a gull-like bird that was the only wildlife I saw during my stay in Antarctica, aside from seals and penguins. -

Primary Ice, Lake Hoare, Antarctica(2015), photograph, 26.75 x 40 inches. Taken at about 1 a.m. under midnight sun, the lake surface is forming what is called "primary ice" in which crystals branch out, forming relief designs that were lit by the slanting sunlight. The designs remind me of Asian ceramics. The ice is framed by reflections of the Canada Glacier and the blue sky.

Primary Ice, Lake Hoare, Antarctica(2015), photograph, 26.75 x 40 inches. Taken at about 1 a.m. under midnight sun, the lake surface is forming what is called "primary ice" in which crystals branch out, forming relief designs that were lit by the slanting sunlight. The designs remind me of Asian ceramics. The ice is framed by reflections of the Canada Glacier and the blue sky. -

Loops and Layers, Lake HoareLoops and Layers, Lake Hoare (2015) photograph, 26.75 x 40 inches. Thin lake ice formations that formed over sediment that has blown onto the surface of the lake.

Loops and Layers, Lake HoareLoops and Layers, Lake Hoare (2015) photograph, 26.75 x 40 inches. Thin lake ice formations that formed over sediment that has blown onto the surface of the lake. -

Vapor Figures and Rainbow, Lake Hoare, AntarcticaVapor Figures and Rainbow, Lake Hoare, Antarctica (2015) photograph, 26.5 x 40 inches. The white etched designs are called Tyndall figures. This formation is richly textured with Tyndalls, frozen bubbles and a colorful interference pattern upper right.

Vapor Figures and Rainbow, Lake Hoare, AntarcticaVapor Figures and Rainbow, Lake Hoare, Antarctica (2015) photograph, 26.5 x 40 inches. The white etched designs are called Tyndall figures. This formation is richly textured with Tyndalls, frozen bubbles and a colorful interference pattern upper right. -

Oblongs, Cape Royds, AntarcticaOblongs, Cape Royds, Antarctica (2015) photograph, 26.75 x 40 inches. These rounded forms are embedded inside the ice. Glaciologists to whom I showed the photo thought maybe these were formed when a layer of water froze on top of scalloped surface ice, though they said the formations were unusual and unfamiliar.

Oblongs, Cape Royds, AntarcticaOblongs, Cape Royds, Antarctica (2015) photograph, 26.75 x 40 inches. These rounded forms are embedded inside the ice. Glaciologists to whom I showed the photo thought maybe these were formed when a layer of water froze on top of scalloped surface ice, though they said the formations were unusual and unfamiliar. -

Ice Ribbons, Lake Ice at Cape Royds, AntarcticaIce Ribbons, Lake Ice at Cape Royds, Antarctica (2015) photograph, 17 x 24 inches inches. These ribbon-like patterns appear embedded inside the ice of the lake a few feet from the shore. I found them at an inland lake at Cape Royds. I showed them to a group of glaciologists who were in Antarctica studying the sea ice. They were intrigued, though they could not explain the cause.

Ice Ribbons, Lake Ice at Cape Royds, AntarcticaIce Ribbons, Lake Ice at Cape Royds, Antarctica (2015) photograph, 17 x 24 inches inches. These ribbon-like patterns appear embedded inside the ice of the lake a few feet from the shore. I found them at an inland lake at Cape Royds. I showed them to a group of glaciologists who were in Antarctica studying the sea ice. They were intrigued, though they could not explain the cause. -

Algal Mat Origami, Cape Royds, Antarctica(2015) photograph, 16.75 x 24 inches or 28 x 40 inches. What looks like torn paper is algal mat that has dried and flaked over blue ice. The ice turns blue when all the air is compressed out of it.

Algal Mat Origami, Cape Royds, Antarctica(2015) photograph, 16.75 x 24 inches or 28 x 40 inches. What looks like torn paper is algal mat that has dried and flaked over blue ice. The ice turns blue when all the air is compressed out of it. -

Sand at Blood Falls, AntarcticaSand at Blood Falls, Antarctica (2015) photograph. The wet sand along the shore of Lake Bonney at Blood Falls was colored by striking shades of green and orange from mineral deposits that seep up and stain the ice.

Sand at Blood Falls, AntarcticaSand at Blood Falls, Antarctica (2015) photograph. The wet sand along the shore of Lake Bonney at Blood Falls was colored by striking shades of green and orange from mineral deposits that seep up and stain the ice. -

Bridge Onto Lake Hoare, AntarcticaBridge Onto Lake Hoare, Antarctica (2015) photograph, 22 x 14.675 inches. When the margin of Lake Hoare melts in the Antarctic summer, the scientists improvise bridges to get onto the ice. This is how I got to the areas I photographed on Lake Hoare for the other photographs of it in this set.

Bridge Onto Lake Hoare, AntarcticaBridge Onto Lake Hoare, Antarctica (2015) photograph, 22 x 14.675 inches. When the margin of Lake Hoare melts in the Antarctic summer, the scientists improvise bridges to get onto the ice. This is how I got to the areas I photographed on Lake Hoare for the other photographs of it in this set. -

Scallopped Sand, Lake Hoare, AntarcticaScallopped Sand, Lake Hoare, Antarctica (2015) photograph, 26.75 x 40 inches. Sand in the shadow of the Canada Glacier in Antarctica, a puddle in the center reflecting the clear blue sky of 24-hour daylight at 1:20 a.m.

Scallopped Sand, Lake Hoare, AntarcticaScallopped Sand, Lake Hoare, Antarctica (2015) photograph, 26.75 x 40 inches. Sand in the shadow of the Canada Glacier in Antarctica, a puddle in the center reflecting the clear blue sky of 24-hour daylight at 1:20 a.m.

Walking in Antarctica: Antarctica in 3D - Sculptures and Source Photos

Walking in Antarctica consists of photographs, sculptures from 3D scans of geological formations, and a first-person audio tour, resulting from a seven-week residency in Antarctica in 2015 through the National Science Foundation Antarctic Artists and Writers Program.

Sculptures based on photographs I took in Antarctica as a grantee of the National Science Foundation's Antarctic Artist and Writers Program allow viewers to experience these geological forms in three-dimensional space, not limited by the fixed perspective of a photograph. I spent a total of seven weeks at the end of 2015 at the U.S. Antarctic Program's McMurdo Station and at scientific field camps. I have developed an innovative method of producing sculpture true to the complexity of the natural world by employing photogrammetry, a process by which a series of still photos of a scene (or "captures") can be assembled by software into a three-dimensional scan of a scene. The scans become the basis for sculptures made with digital fabrication technologies such as 3D printing or CNC (computer-controlled) routers, a machine that can carve a 3D file in a variety of materials. On the router I typically use high-density urethane foam for its ability to hold detail yet be easily carved later with hand tools. The scan produced by the photogrammetric software is by no means ready for production. A variety of artistic decisions must be made, and small areas of the form that the software could not resolve have to be filled in using 3D modeling software, a painstaking process because the files are extremely complex — each scan consists of some 2 million tiny triangular facets. Once the piece has been carved or printed in sections and glued together, I refine the piece by hand and paint it. If I had the funding, I could produce them in higher-quality materials such as cast stone or metal.

-

Canada Glacier from Lake Fryxell, AntarcticaCanada Glacier from Lake Fryxell, Antarctica (2015), archival pigment print, 32.5 x 50 inches. Section of the Canada Glacier captured in the 3D file. A section of the massive, spired 60-foot-high side of the Canada Glacier photographed from the frozen surface of Lake Fryxell. The journey here entailed crossing the melted margin in a rowboat used by lake scientists and a bumpy ride over the ice on an ATV.

Canada Glacier from Lake Fryxell, AntarcticaCanada Glacier from Lake Fryxell, Antarctica (2015), archival pigment print, 32.5 x 50 inches. Section of the Canada Glacier captured in the 3D file. A section of the massive, spired 60-foot-high side of the Canada Glacier photographed from the frozen surface of Lake Fryxell. The journey here entailed crossing the melted margin in a rowboat used by lake scientists and a bumpy ride over the ice on an ATV. -

Canada Glacier from Lake Fryxell, AntarcticaCanada Glacier from Lake Fryxell, Antarctica (2015), archival pigment print, 32.5 x 50 inches. Section of the Canada Glacier captured in the 3D file. A section of the massive, spired 60-foot-high side of the Canada Glacier photographed from the frozen surface of Lake Fryxell. The journey here entailed crossing the melted margin in a rowboat used by lake scientists and a bumpy ride over the ice on an ATV.

Canada Glacier from Lake Fryxell, AntarcticaCanada Glacier from Lake Fryxell, Antarctica (2015), archival pigment print, 32.5 x 50 inches. Section of the Canada Glacier captured in the 3D file. A section of the massive, spired 60-foot-high side of the Canada Glacier photographed from the frozen surface of Lake Fryxell. The journey here entailed crossing the melted margin in a rowboat used by lake scientists and a bumpy ride over the ice on an ATV. -

2024-0504-8.jpg

2024-0504-8.jpgInstallation of the Canada Glacier from Lake Fryxell sculpture on view at the Juliet Art Museum, Clay Center, Charleston, West Virginia, in 2024 as part of Walking in Antarctica.

-

CanadaGlacier-2015-12-19_Panorama.jpg

CanadaGlacier-2015-12-19_Panorama.jpgPanorama of Canada Glacier from Lake Fryxell, Antarctica (2015) photograph, 16.5 x 73 inches. The panorama gives some perspective on the size of the glacier. The area I photographed to make the 3D scan for the sculpture is on the left, centered in the area adjoining the lake.

-

Canada Glacier from Lake Hoare, AntarcticaCanada Glacier from Lake Hoare, Antarctica (2017) acrylic on 3D-printed PLA plastic, 11 x 54 x 15.5 inches. Sculpture of the west-facing side of the Canada Glacier. The basic 3D scan was generated via photogrammetry from still photographs and further edited. I printed it in sections, epoxied them together and painted it in acrylics.

Canada Glacier from Lake Hoare, AntarcticaCanada Glacier from Lake Hoare, Antarctica (2017) acrylic on 3D-printed PLA plastic, 11 x 54 x 15.5 inches. Sculpture of the west-facing side of the Canada Glacier. The basic 3D scan was generated via photogrammetry from still photographs and further edited. I printed it in sections, epoxied them together and painted it in acrylics. -

Canada Glacier from Lake Hoare, AntarcticaCanada Glacier from Lake Hoare, Antarctica (2015) archival pigment print, 26.5 x 40 inches. The west facing side of the Canada Glacier rests alongside the Lake Hoare field camp. A row of sandbags has been placed at the edge of the area where meltwater flows in a stream during the austral summer.

Canada Glacier from Lake Hoare, AntarcticaCanada Glacier from Lake Hoare, Antarctica (2015) archival pigment print, 26.5 x 40 inches. The west facing side of the Canada Glacier rests alongside the Lake Hoare field camp. A row of sandbags has been placed at the edge of the area where meltwater flows in a stream during the austral summer. -

2024-0201 Fairfield-2-3.jpg

2024-0201 Fairfield-2-3.jpgGiant's Face" Pressure Ridge, McMurdo Sound, Antarctica (2017) acrylic, oil and wax on 3D-printed PLA plastic and polymer-modified gypsum, 19.5 x 36 x 15.5 inches, with one of the source photographs above it, 22 x 15.675 inches. Sculpture of a 20-foot-high Baroque looking sea ice pressure ridge in a remote section of New Harbor. The basic 3D scan was generated via photogrammetry, further edited, printed in sections and epoxied together. I added the icicles by hand and then painted it. This photo is from the installation of Walking in Antarctica at the Fairfield University Art Museum in 2024.

-

2024-0304 Fairfield-5-2.jpg

2024-0304 Fairfield-5-2.jpgThis alcove of the Fairfield University Art Museum's 2024 installation of Walking in Antarctica includes photographs and sculptures from the section of the exhibition titled "A Walk Over the Canada Glacier."

Walking in Antarctica: Ventifacts & Blood Falls, Dry Valleys, Antarctica

Walking in Antarctica consists of photographs, sculptures from 3D scans of geological formations, and a first-person audio tour, resulting from a seven-week residency in Antarctica in 2015 through the National Science Foundation Antarctic Artists and Writers Program.

On Dec. 16th, 2015, with a mountaineer guide, I visited Blood Falls, a glacier stained with unique iron formations. The following day, the guide and I hiked up some steep gravel inclines in the McMurdo Dry Valleys above Lake Bonney to elevated ridges and plateaus to see the ventifacts. These are large granite boulders that have been pummeled by fierce winds picking up grains of gravel — imagine a giant sandblaster over millennia. It was a steady climb for well over an hour and then we came over a ridge where the ground was strewn with huge granite boulders curved, hollowed and pierced into strange shapes. I felt like I’d entered the world’s largest Surrealist sculpture garden. I circled the formations shown here with the eventual intention of creating 3D files from still photos via photogrammetry (see the Antarctica in 3D section for general information about the process).

The Dry Valleys are the largest relatively ice-free region in Antarctica, encompassing a cold and windy desert ecosystem with lakes that have a permanently frozen cover of about 4 meters of ice and rare life forms (mostly microorganisms) that have adapted to the extreme conditions — these are active for only two to three months a year and otherwise lie dormant. By international treaty, they are an Antarctic Specially Managed Area. Other than the small number of scientists and science support personnel who do research in the Dry Valleys during the austral summer, very few people have even seen the ventifact fields. Even fewer have been allowed to visit Blood Falls, which is an Antarctic Specially Protected Area and requires an additional permit be issued in advance from a national Antarctic program.

-

"Seated Figure" Ventifact, Dry Valleys, Antarctica"Seated Figure" Ventifact, Dry Valleys, Antarctica (2015), photograph, 14.675 x 22 inches. The ventifacts present very different sculptural profiles as you walk around them. None of the ventifacts have official names. Any names in quotes are ones I gave them for reference. This one reminded me of a seated figure.

"Seated Figure" Ventifact, Dry Valleys, Antarctica"Seated Figure" Ventifact, Dry Valleys, Antarctica (2015), photograph, 14.675 x 22 inches. The ventifacts present very different sculptural profiles as you walk around them. None of the ventifacts have official names. Any names in quotes are ones I gave them for reference. This one reminded me of a seated figure. -

"Seated Figure" Ventifact, Dry Valleys, Antarctica"Seated Figure" Ventifact, Dry Valleys, Antarctica (2015) photograph. The ventifacts present very different sculptural profiles as you walk around them. Compare this to the previous and following photo of the same formation. None of the ventifacts have official names. Any names in quotes are ones I gave them for reference.

"Seated Figure" Ventifact, Dry Valleys, Antarctica"Seated Figure" Ventifact, Dry Valleys, Antarctica (2015) photograph. The ventifacts present very different sculptural profiles as you walk around them. Compare this to the previous and following photo of the same formation. None of the ventifacts have official names. Any names in quotes are ones I gave them for reference. -

Matterhorn Framed by Ventifacts, Dry Valleys, AntarcticaMatterhorn Framed by Ventifacts, Dry Valleys, Antarctica (2015), photograph, 22.375 x 15 inches. This is another view of the "Seated Figure" ventifact shown in two other photographs. It frames a view of a mountain peak on the opposite side of the valley called The Matterhorn.

Matterhorn Framed by Ventifacts, Dry Valleys, AntarcticaMatterhorn Framed by Ventifacts, Dry Valleys, Antarctica (2015), photograph, 22.375 x 15 inches. This is another view of the "Seated Figure" ventifact shown in two other photographs. It frames a view of a mountain peak on the opposite side of the valley called The Matterhorn. -

"Tanguy" Ventifact, Dry Valleys, Antarctica"Tanguy" Ventifact, Dry Valleys, Antarctica (2015), photograph,13.75 x 22 inches. None of the ventifacts have official names. Any names in quotes are ones I gave them for reference. This one reminds me of Surrealist landscape paintings by Yves Tanguy from the mid 20th century. It is also a source photo intended for eventual processing as a 3D file and sculpture.

"Tanguy" Ventifact, Dry Valleys, Antarctica"Tanguy" Ventifact, Dry Valleys, Antarctica (2015), photograph,13.75 x 22 inches. None of the ventifacts have official names. Any names in quotes are ones I gave them for reference. This one reminds me of Surrealist landscape paintings by Yves Tanguy from the mid 20th century. It is also a source photo intended for eventual processing as a 3D file and sculpture. -

06 Glazer Bird Ventifact.jpg"Bird" Ventifact, Dry Valleys, Antarctica (2015) photograph, 14.75 x 22 inches. Source photo for the 3D scan from which I made the sculpture shown in other images of this project. None has an official name, but it reminded me of a bird.

06 Glazer Bird Ventifact.jpg"Bird" Ventifact, Dry Valleys, Antarctica (2015) photograph, 14.75 x 22 inches. Source photo for the 3D scan from which I made the sculpture shown in other images of this project. None has an official name, but it reminded me of a bird. -

"Bird" Ventifact, Dry Valleys, Antarctica"Bird" Ventifact, Dry Valleys, Antarctica (2016), acrylic on 3D-printed PLA plastic and polymer-modified gypsum, 16 x 29.5 x 29.5 inches. At the top of the steep, gravel-covered hill above Lake Bonney in the McMurdo Dry Valleys is a plateau strewn with ventifacts, giant boulders eroded into strange shapes by fierce winds. I called it the Surrealist sculpture garden. I made a 3D scan of this six-foot-tall boulder and printed it in sections on a 3D printer. A video of the process is shown on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qdY3xDGPDf0

"Bird" Ventifact, Dry Valleys, Antarctica"Bird" Ventifact, Dry Valleys, Antarctica (2016), acrylic on 3D-printed PLA plastic and polymer-modified gypsum, 16 x 29.5 x 29.5 inches. At the top of the steep, gravel-covered hill above Lake Bonney in the McMurdo Dry Valleys is a plateau strewn with ventifacts, giant boulders eroded into strange shapes by fierce winds. I called it the Surrealist sculpture garden. I made a 3D scan of this six-foot-tall boulder and printed it in sections on a 3D printer. A video of the process is shown on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qdY3xDGPDf0 -

"Bird" Ventifact, Dry Valleys, Antarctica"Bird" Ventifact, Dry Valleys, Antarctica (2016), acrylic on 3D-printed PLA plastic and polymer-modified gypsum, 16 x 29.5 x 29.5 inches. At the top of the steep, gravel-covered hill above Lake Bonney in the McMurdo Dry Valleys is a plateau strewn with ventifacts, giant boulders eroded into strange shapes by fierce winds. I called it the Surrealist sculpture garden. I made a 3D scan of this six-foot-tall boulder and printed it in sections on a 3D printer. A video of the process is shown on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qdY3xDGPDf0

"Bird" Ventifact, Dry Valleys, Antarctica"Bird" Ventifact, Dry Valleys, Antarctica (2016), acrylic on 3D-printed PLA plastic and polymer-modified gypsum, 16 x 29.5 x 29.5 inches. At the top of the steep, gravel-covered hill above Lake Bonney in the McMurdo Dry Valleys is a plateau strewn with ventifacts, giant boulders eroded into strange shapes by fierce winds. I called it the Surrealist sculpture garden. I made a 3D scan of this six-foot-tall boulder and printed it in sections on a 3D printer. A video of the process is shown on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qdY3xDGPDf0 -

"Bird" Ventifact, Dry Valleys, Antarctica"Bird" Ventifact, Dry Valleys, Antarctica (2016), acrylic on 3D-printed PLA plastic and polymer-modified gypsum, 16 x 29.5 x 29.5 inches. At the top of the steep, gravel-covered hill above Lake Bonney in the McMurdo Dry Valleys is a plateau strewn with ventifacts, giant boulders eroded into strange shapes by fierce winds. I called it the Surrealist sculpture garden. I made a 3D scan of this six-foot-tall boulder and printed it in sections on a 3D printer. A video of the process is shown on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qdY3xDGPDf0

"Bird" Ventifact, Dry Valleys, Antarctica"Bird" Ventifact, Dry Valleys, Antarctica (2016), acrylic on 3D-printed PLA plastic and polymer-modified gypsum, 16 x 29.5 x 29.5 inches. At the top of the steep, gravel-covered hill above Lake Bonney in the McMurdo Dry Valleys is a plateau strewn with ventifacts, giant boulders eroded into strange shapes by fierce winds. I called it the Surrealist sculpture garden. I made a 3D scan of this six-foot-tall boulder and printed it in sections on a 3D printer. A video of the process is shown on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qdY3xDGPDf0 -

"Pterodactyl" Ventifact, Dry Valleys, Antarctica(2015/2019) archival pigment print, 12 x 18 inches. At the top of the steep, gravel-covered hill above Lake Bonney is a plateau strewn with ventifacts, giant boulders eroded into strange shapes by freeze/thaw cycles and fierce winds. This is one of the source photos for the sculpture also shown here.

"Pterodactyl" Ventifact, Dry Valleys, Antarctica(2015/2019) archival pigment print, 12 x 18 inches. At the top of the steep, gravel-covered hill above Lake Bonney is a plateau strewn with ventifacts, giant boulders eroded into strange shapes by freeze/thaw cycles and fierce winds. This is one of the source photos for the sculpture also shown here. -

"Pterodactyl" Ventifact, Dry Valleys, Antarctica(2019) acrylic on 3D-printed PLA plastic, 16 x 24.5 x 29.5 inches. 3D printed sculpture generated from still photos taken on site, via photogrammetry.

"Pterodactyl" Ventifact, Dry Valleys, Antarctica(2019) acrylic on 3D-printed PLA plastic, 16 x 24.5 x 29.5 inches. 3D printed sculpture generated from still photos taken on site, via photogrammetry.