Work samples

-

CoccolithophoreCoccolithophores are a type of unicellular phytoplankton (cyanobacteria), maybe best known for being the main ingredient of chalk. These tiny organisms use photosynthesis to take in carbon, which they use to make their make their calcium carbonate exoskeletons. When they die, their exoskeletons sink to the ocean floor, trapping carbon far away from the atmosphere. Ancient chalk deposits like the White Cliffs of Dover were once at the bottom of the ocean. They are made of long deceased, compressed coccolithophore exoskeletons. Coccolithophores live in the oceans in vast numbers. Not only are they a major producer of oxygen (and carbon sink), they are also some of the most abundant primary producers at the bottom of the food web, providing sustenance to larger and more complex marine organisms. They also produce DMS (dimethyl sulphide), a compound which encourages cloud formation and by extension helps cool our planet.

CoccolithophoreCoccolithophores are a type of unicellular phytoplankton (cyanobacteria), maybe best known for being the main ingredient of chalk. These tiny organisms use photosynthesis to take in carbon, which they use to make their make their calcium carbonate exoskeletons. When they die, their exoskeletons sink to the ocean floor, trapping carbon far away from the atmosphere. Ancient chalk deposits like the White Cliffs of Dover were once at the bottom of the ocean. They are made of long deceased, compressed coccolithophore exoskeletons. Coccolithophores live in the oceans in vast numbers. Not only are they a major producer of oxygen (and carbon sink), they are also some of the most abundant primary producers at the bottom of the food web, providing sustenance to larger and more complex marine organisms. They also produce DMS (dimethyl sulphide), a compound which encourages cloud formation and by extension helps cool our planet. -

MedusaeOil on wood, 18x18", 2020. These are jellyfish in the medusa stage. Their complex life cycle is part of what makes jellyfish so resilient to changing water conditions such as warming and acidification. They begin their lives as a polyp, which can survive for many years until conditions are right—then they bud into a strobila, a stack of jellyfish clones that grows off the polyp. Each strobila at the top of the stack will eventually break off, and then feed until they turn into medusae. The medusae reproduce sexually, their sperm and eggs combining to form planktonic spores which turn into more polyps once they attach themselves to a surface. When other marine species are threatened, jellyfish often take over. Many species of jellyfish are extremely resilient; they can regenerate their flesh, survive for long periods without food, reproduce in staggering numbers, and often thrive in warming waters. (One species, Turritopsis dohrnii, is considered biologically immortal). They also have a low nutritional value, and in some ecosystems have few known predators. Many creatures that do eat jellyfish, including albatrosses, tuna, swordfish, and sea turtles, are now considered threatened species due to overfishing and climate change. I was inspired to create a series of paintings exploring the complex web of relationships in the ocean after attending a lecture by environmental artist Stacy Levy. Water has unique properties that make it the fundamental source of life on Earth, and through my paintings I explore how it looks, how it moves, and the complex ways in which it connects our world.

MedusaeOil on wood, 18x18", 2020. These are jellyfish in the medusa stage. Their complex life cycle is part of what makes jellyfish so resilient to changing water conditions such as warming and acidification. They begin their lives as a polyp, which can survive for many years until conditions are right—then they bud into a strobila, a stack of jellyfish clones that grows off the polyp. Each strobila at the top of the stack will eventually break off, and then feed until they turn into medusae. The medusae reproduce sexually, their sperm and eggs combining to form planktonic spores which turn into more polyps once they attach themselves to a surface. When other marine species are threatened, jellyfish often take over. Many species of jellyfish are extremely resilient; they can regenerate their flesh, survive for long periods without food, reproduce in staggering numbers, and often thrive in warming waters. (One species, Turritopsis dohrnii, is considered biologically immortal). They also have a low nutritional value, and in some ecosystems have few known predators. Many creatures that do eat jellyfish, including albatrosses, tuna, swordfish, and sea turtles, are now considered threatened species due to overfishing and climate change. I was inspired to create a series of paintings exploring the complex web of relationships in the ocean after attending a lecture by environmental artist Stacy Levy. Water has unique properties that make it the fundamental source of life on Earth, and through my paintings I explore how it looks, how it moves, and the complex ways in which it connects our world.

About Madeleine

I have enjoyed working in many different mediums as a designer and a teacher. These days, my media of choice are oil painting and ceramics. My work allows me to combine my interest in science and ecology with my desire to study complex natural forms and textures. Through the study and reinterpretation of natural forms and relationships, my process serves as a meditation on small pieces that comprise the delicate balance of life. As I collect new imagery and ideas over time… more

Jump to a project:

Vessels (2020)

"Vessels" is an ongoing series of paintings depicting pieces of the web of life dependent on the ocean. The painted forms of the organisms I've chosen to study are filled with water, the fundamental source of all life. Our shared ancestors came from the ocean, which remains a basis of interconnectedness for all beings on Earth. Coevolution over eons has made these organisms in this web interdependent on each other in untold ways; without any one of them, the balance is thrown off for the others.

-

Sky Call (Albatross)Oil on wood, 18x24", 2020. Since I first learned about the dances of albatrosses (from David Attenborough, who else), I’ve had an admiration for the way these birds conduct their relationships. Though they spend months apart from each other traveling vast distances alone over the seas, when they reunite on land they greet each other by dancing. Each couple has their own unique sequence of head-bobs, beak-clacks, and wing-spreading flourishes which they have choreographed together. Albatross dances change and evolve throughout the course of their life-long partnerships, which can last for 50 years, depending on the species. I was inspired to create a series of paintings exploring the complex web of relationships in the ocean after attending a lecture by environmental artist Stacy Levy. Water has unique properties that make it the fundamental source of life on Earth, and through my paintings I explore how it looks, how it moves, and the complex ways in which it connects our world.

Sky Call (Albatross)Oil on wood, 18x24", 2020. Since I first learned about the dances of albatrosses (from David Attenborough, who else), I’ve had an admiration for the way these birds conduct their relationships. Though they spend months apart from each other traveling vast distances alone over the seas, when they reunite on land they greet each other by dancing. Each couple has their own unique sequence of head-bobs, beak-clacks, and wing-spreading flourishes which they have choreographed together. Albatross dances change and evolve throughout the course of their life-long partnerships, which can last for 50 years, depending on the species. I was inspired to create a series of paintings exploring the complex web of relationships in the ocean after attending a lecture by environmental artist Stacy Levy. Water has unique properties that make it the fundamental source of life on Earth, and through my paintings I explore how it looks, how it moves, and the complex ways in which it connects our world. -

Right Whale (Eubalaena glacialis)Oil on wood, 24x36", 2020. There are only about 400 North Atlantic right whales left in the world. They’ve been protected from whaling since 1935, but their population has never recovered from when they were hunted for their baleens and oil. They got their name from whalers who called them the “right whale” to hunt because they tend to swim slowly and near the surface. Today, these whales’ biggest threats are being struck by ships or entangled in commercial fishing gear. 85% of them show signs of having been entangled in fishing gear at some point in their lives. They are also threatened by ship noise and sonar testing. They live along the coasts of North America and (increasingly rarely) near European coasts. Their distribution is shifting as their food sources move to adapt to changes in the ocean. Their primary source of food is a tiny 2mm crustacean, a copepod species called Calanus finmarchicus. Due to changing temperatures and salinity levels, the density and distribution of C. finmarchicus is changing, forcing the small population of right whales to try to quickly adapt. Meanwhile, giant algae blooms like the one inside this whale’s silhouette, are on the rise. These blooms are comprised of tiny phytoplankton like diatoms, dinoflagellates, and cyanobacteria, and are a yearly occurrence in many places. Due to warming waters and phosphorus runoff from sewage and agriculture, they are becoming more frequent and intense, disrupting marine ecosystems. Large blooms can threaten other life dependent on the waters they bloom in by releasing toxic substances or depleting the water of oxygen, creating “dead zones” in the ocean. Some blooms can also cause illness in humans, and harm coastal economies. I was inspired to create a series of paintings exploring the complex web of relationships in the ocean after attending a lecture by environmental artist Stacy Levy. Water has unique properties that make it the fundamental source of life on Earth, and through my paintings I explore how it looks, how it moves, and the complex ways in which it connects our world.

Right Whale (Eubalaena glacialis)Oil on wood, 24x36", 2020. There are only about 400 North Atlantic right whales left in the world. They’ve been protected from whaling since 1935, but their population has never recovered from when they were hunted for their baleens and oil. They got their name from whalers who called them the “right whale” to hunt because they tend to swim slowly and near the surface. Today, these whales’ biggest threats are being struck by ships or entangled in commercial fishing gear. 85% of them show signs of having been entangled in fishing gear at some point in their lives. They are also threatened by ship noise and sonar testing. They live along the coasts of North America and (increasingly rarely) near European coasts. Their distribution is shifting as their food sources move to adapt to changes in the ocean. Their primary source of food is a tiny 2mm crustacean, a copepod species called Calanus finmarchicus. Due to changing temperatures and salinity levels, the density and distribution of C. finmarchicus is changing, forcing the small population of right whales to try to quickly adapt. Meanwhile, giant algae blooms like the one inside this whale’s silhouette, are on the rise. These blooms are comprised of tiny phytoplankton like diatoms, dinoflagellates, and cyanobacteria, and are a yearly occurrence in many places. Due to warming waters and phosphorus runoff from sewage and agriculture, they are becoming more frequent and intense, disrupting marine ecosystems. Large blooms can threaten other life dependent on the waters they bloom in by releasing toxic substances or depleting the water of oxygen, creating “dead zones” in the ocean. Some blooms can also cause illness in humans, and harm coastal economies. I was inspired to create a series of paintings exploring the complex web of relationships in the ocean after attending a lecture by environmental artist Stacy Levy. Water has unique properties that make it the fundamental source of life on Earth, and through my paintings I explore how it looks, how it moves, and the complex ways in which it connects our world. -

MedusaeOil on wood, 18x18", 2020. These are jellyfish in the medusa stage. Their complex life cycle is part of what makes jellyfish so resilient to changing water conditions such as warming and acidification. They begin their lives as a polyp, which can survive for many years until conditions are right—then they bud into a strobila, a stack of jellyfish clones that grows off the polyp. Each strobila at the top of the stack will eventually break off, and then feed until they turn into medusae. The medusae reproduce sexually, their sperm and eggs combining to form planktonic spores which turn into more polyps once they attach themselves to a surface. When other marine species are threatened, jellyfish often take over. Many species of jellyfish are extremely resilient; they can regenerate their flesh, survive for long periods without food, reproduce in staggering numbers, and often thrive in warming waters. (One species, Turritopsis dohrnii, is considered biologically immortal). They also have a low nutritional value, and in some ecosystems have few known predators. Many creatures that do eat jellyfish, including albatrosses, tuna, swordfish, and sea turtles, are now considered threatened species due to overfishing and climate change. I was inspired to create a series of paintings exploring the complex web of relationships in the ocean after attending a lecture by environmental artist Stacy Levy. Water has unique properties that make it the fundamental source of life on Earth, and through my paintings I explore how it looks, how it moves, and the complex ways in which it connects our world.

MedusaeOil on wood, 18x18", 2020. These are jellyfish in the medusa stage. Their complex life cycle is part of what makes jellyfish so resilient to changing water conditions such as warming and acidification. They begin their lives as a polyp, which can survive for many years until conditions are right—then they bud into a strobila, a stack of jellyfish clones that grows off the polyp. Each strobila at the top of the stack will eventually break off, and then feed until they turn into medusae. The medusae reproduce sexually, their sperm and eggs combining to form planktonic spores which turn into more polyps once they attach themselves to a surface. When other marine species are threatened, jellyfish often take over. Many species of jellyfish are extremely resilient; they can regenerate their flesh, survive for long periods without food, reproduce in staggering numbers, and often thrive in warming waters. (One species, Turritopsis dohrnii, is considered biologically immortal). They also have a low nutritional value, and in some ecosystems have few known predators. Many creatures that do eat jellyfish, including albatrosses, tuna, swordfish, and sea turtles, are now considered threatened species due to overfishing and climate change. I was inspired to create a series of paintings exploring the complex web of relationships in the ocean after attending a lecture by environmental artist Stacy Levy. Water has unique properties that make it the fundamental source of life on Earth, and through my paintings I explore how it looks, how it moves, and the complex ways in which it connects our world. -

Copepod (Calanus finmarchicus)Oil on wood, 14x11", 2020. This is Calanus finmarchicus, a species of copepod (tiny marine crustacean) that is the primary food source for North Atlantic right whales. Only about 2mm long, they feed on diatoms, dinoflagellates, and other microplankton. They dwell in the North Atlantic from the Gulf of Maine to the Norwegian Sea, but can be adaptable to a wide variety of conditions; they have survived periods of climate change in the past by migrating and overwintering in deeper waters. Their biomass in the North Sea has declined by 70% since 1960. Scientists may be able to better understand some of the current changes in climate by tracking shifts in copepod populations’ distribution over time. I was inspired to create a series of paintings exploring the complex web of relationships in the ocean after attending a lecture by environmental artist Stacy Levy. Water has unique properties that make it the fundamental source of life on Earth, and through my paintings I explore how it looks, how it moves, and the complex ways in which it connects our world.

Copepod (Calanus finmarchicus)Oil on wood, 14x11", 2020. This is Calanus finmarchicus, a species of copepod (tiny marine crustacean) that is the primary food source for North Atlantic right whales. Only about 2mm long, they feed on diatoms, dinoflagellates, and other microplankton. They dwell in the North Atlantic from the Gulf of Maine to the Norwegian Sea, but can be adaptable to a wide variety of conditions; they have survived periods of climate change in the past by migrating and overwintering in deeper waters. Their biomass in the North Sea has declined by 70% since 1960. Scientists may be able to better understand some of the current changes in climate by tracking shifts in copepod populations’ distribution over time. I was inspired to create a series of paintings exploring the complex web of relationships in the ocean after attending a lecture by environmental artist Stacy Levy. Water has unique properties that make it the fundamental source of life on Earth, and through my paintings I explore how it looks, how it moves, and the complex ways in which it connects our world.

Marine Microcosmos (2020)

"Marine Microcosmos" is a series of paintings of microorganisms that are found in water, particularly in the oceans. A vast world of near-invisible microscopic organisms is responsible for making the Earth habitable for creatures like us. They provide our oxygen, store CO2 away from our atmosphere, feed the organisms which ultimately provide us sustenance, and so much more. By learning about them and creating paintings based on what I learn, I hope to bring to light these important allies which are all too easy to overlook.

-

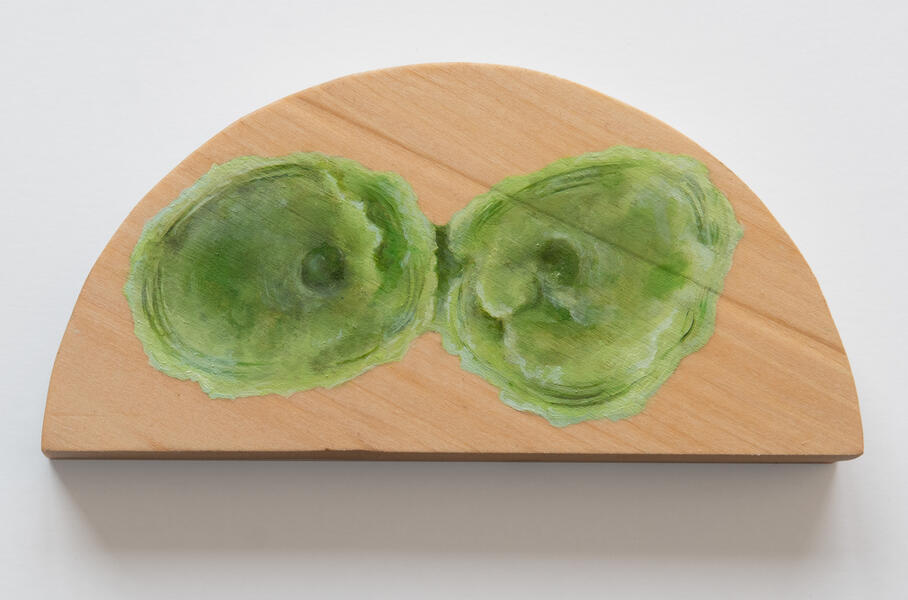

ProchlorococcusProchlorococcus is a type of single-celled marine algae that is thought to be responsible for 5% of the photosynthesis that takes place on our planet. They survive on sunlight, seawater, and CO2. With a population of approximately 10^27, they are some of the most prolific primary producers on Earth, and play a huge role in the carbon cycle and in the food web. This painting shows a Prochlorococcus in the process of cell division.

ProchlorococcusProchlorococcus is a type of single-celled marine algae that is thought to be responsible for 5% of the photosynthesis that takes place on our planet. They survive on sunlight, seawater, and CO2. With a population of approximately 10^27, they are some of the most prolific primary producers on Earth, and play a huge role in the carbon cycle and in the food web. This painting shows a Prochlorococcus in the process of cell division. -

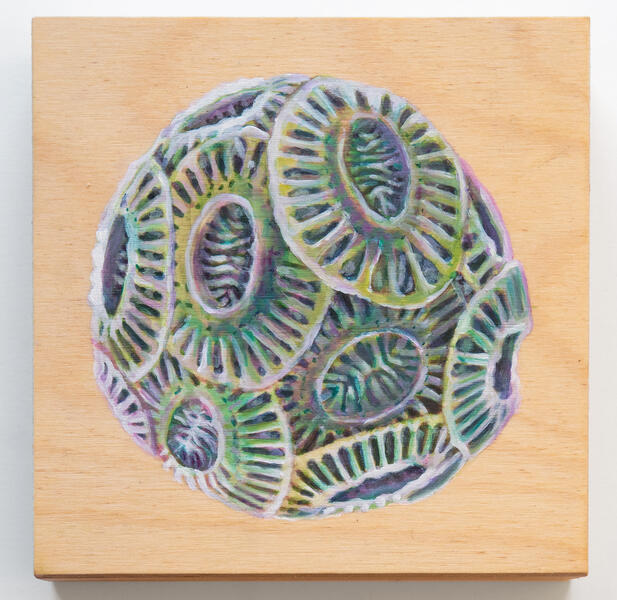

Symbiodinium (Zooxanthellae)Symbiodinium are a type of single-celled dinoflagellate algae which have symbiotic relationships to many marine invertebrates including jellyfish and nudibranchs. They are best known, however, for their symbiotic relationship to reef-building corals. They use photosynthesis to transform sunlight and CO2 into sugar, which they produce enough of to share with the corals. The corals in return provide them a safe habitat, nutrients, and CO2. Coral bleaching occurs when corals lose their colorful symbiodinium communities due to altered conditions such as warming and acidification. Without symbiodinium to sustain them, corals starve and die off.

Symbiodinium (Zooxanthellae)Symbiodinium are a type of single-celled dinoflagellate algae which have symbiotic relationships to many marine invertebrates including jellyfish and nudibranchs. They are best known, however, for their symbiotic relationship to reef-building corals. They use photosynthesis to transform sunlight and CO2 into sugar, which they produce enough of to share with the corals. The corals in return provide them a safe habitat, nutrients, and CO2. Coral bleaching occurs when corals lose their colorful symbiodinium communities due to altered conditions such as warming and acidification. Without symbiodinium to sustain them, corals starve and die off. -

CoccolithophoreCoccolithophores are a type of unicellular phytoplankton (cyanobacteria), maybe best known for being the main ingredient of chalk. These tiny organisms use photosynthesis to take in carbon, which they use to make their make their calcium carbonate exoskeletons. When they die, their exoskeletons sink to the ocean floor, trapping carbon far away from the atmosphere. Ancient chalk deposits like the White Cliffs of Dover were once at the bottom of the ocean. They are made of long deceased, compressed coccolithophore exoskeletons. Coccolithophores live in the oceans in vast numbers. Not only are they a major producer of oxygen (and carbon sink), they are also some of the most abundant primary producers at the bottom of the food web, providing sustenance to larger and more complex marine organisms. They also produce DMS (dimethyl sulphide), a compound which encourages cloud formation and by extension helps cool our planet.

CoccolithophoreCoccolithophores are a type of unicellular phytoplankton (cyanobacteria), maybe best known for being the main ingredient of chalk. These tiny organisms use photosynthesis to take in carbon, which they use to make their make their calcium carbonate exoskeletons. When they die, their exoskeletons sink to the ocean floor, trapping carbon far away from the atmosphere. Ancient chalk deposits like the White Cliffs of Dover were once at the bottom of the ocean. They are made of long deceased, compressed coccolithophore exoskeletons. Coccolithophores live in the oceans in vast numbers. Not only are they a major producer of oxygen (and carbon sink), they are also some of the most abundant primary producers at the bottom of the food web, providing sustenance to larger and more complex marine organisms. They also produce DMS (dimethyl sulphide), a compound which encourages cloud formation and by extension helps cool our planet. -

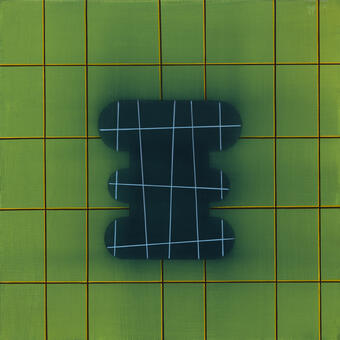

DiatomDiatoms are unicellular algae best known for the beautiful colors and geometric shapes of their cell walls, which are composed of silica. These tiny organisms use photosynthesis to take in CO2, trapping carbon and releasing oxygen. At the end of their lives, their heavy shells sink to the ocean floor, trapping CO2 away from the atmosphere. Though they are tiny as individual organisms, the biomass of diatoms is enormous, as is their effect on our world. Over millions of years, diatoms and other ocean microbes, such as foraminifera, are responsible for building up the oxygen levels in the Earth’s atmosphere to what they are today. There may be as many as 2 million diatom species, inhabiting virtually every kind of wet environment on Earth.

DiatomDiatoms are unicellular algae best known for the beautiful colors and geometric shapes of their cell walls, which are composed of silica. These tiny organisms use photosynthesis to take in CO2, trapping carbon and releasing oxygen. At the end of their lives, their heavy shells sink to the ocean floor, trapping CO2 away from the atmosphere. Though they are tiny as individual organisms, the biomass of diatoms is enormous, as is their effect on our world. Over millions of years, diatoms and other ocean microbes, such as foraminifera, are responsible for building up the oxygen levels in the Earth’s atmosphere to what they are today. There may be as many as 2 million diatom species, inhabiting virtually every kind of wet environment on Earth. -

Phaeocystis pouchetiiA colony of Phaeocystis pouchetii, which is a microorganism that produces an important compound called dimethylsulfide (DMS). DMS in the ocean causes sea foam to form and the smell of sea foam. That smell draws sea birds like albatrosses to feed (organisms like krill, which the birds eat, feed on the Phaeocystis). DMS also encourages cloud formation by giving water droplets something to stick to, which in turn helps cool the planet.

Phaeocystis pouchetiiA colony of Phaeocystis pouchetii, which is a microorganism that produces an important compound called dimethylsulfide (DMS). DMS in the ocean causes sea foam to form and the smell of sea foam. That smell draws sea birds like albatrosses to feed (organisms like krill, which the birds eat, feed on the Phaeocystis). DMS also encourages cloud formation by giving water droplets something to stick to, which in turn helps cool the planet. -

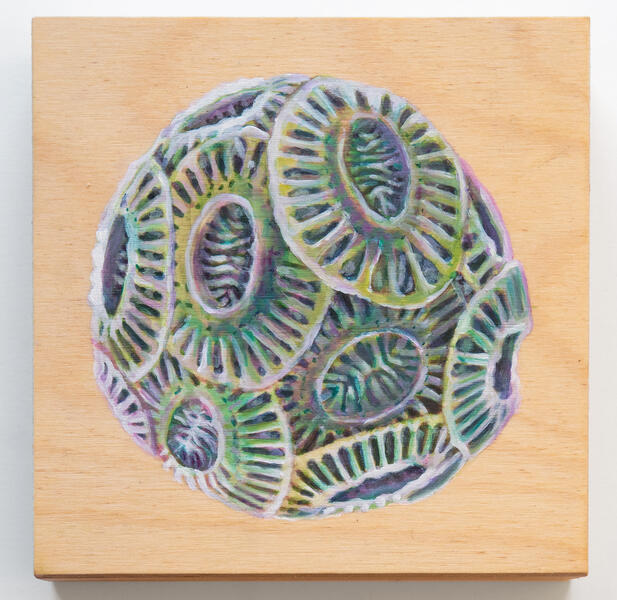

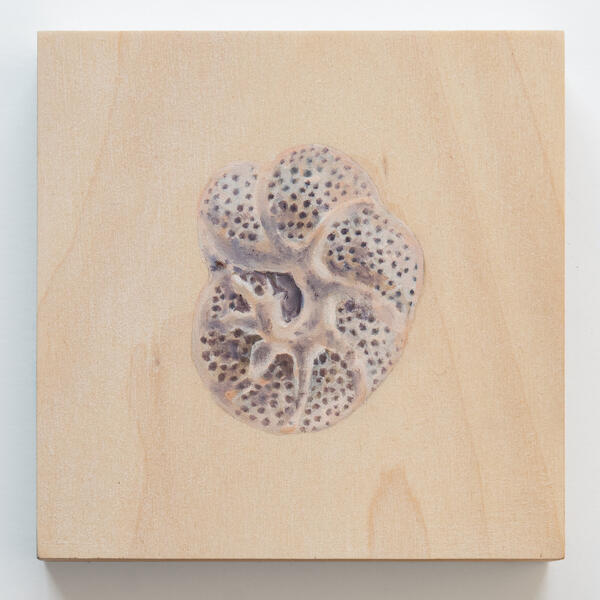

ForaminiferaForaminifera are single-celled marine organisms. Their shells are covered in tiny holes called foramen (Latin for “window”), which they push their ectoplasm through to create pseudopodia (false legs) which they use to move about and collect food. They eat other microorganisms such as diatoms as well as detritus from the sea floor. Foraminifera shells are made of calcium carbonate. When forams die, their shells settle on the sea floor as sediment, which eventually turns to limestone under pressure. The stone and sediment they leave behind sequesters vast amounts of carbon away from our atmosphere. Over millions of years, forams were instrumental in transforming the Earth’s atmosphere into the oxygen-rich air we breathe today.

ForaminiferaForaminifera are single-celled marine organisms. Their shells are covered in tiny holes called foramen (Latin for “window”), which they push their ectoplasm through to create pseudopodia (false legs) which they use to move about and collect food. They eat other microorganisms such as diatoms as well as detritus from the sea floor. Foraminifera shells are made of calcium carbonate. When forams die, their shells settle on the sea floor as sediment, which eventually turns to limestone under pressure. The stone and sediment they leave behind sequesters vast amounts of carbon away from our atmosphere. Over millions of years, forams were instrumental in transforming the Earth’s atmosphere into the oxygen-rich air we breathe today. -

TardigradeAlso known as “water bears” or “moss piglets,” tardigrades are widely known for their ability to survive even after being exposed to outer space, as well as for being some of the cutest microorganisms. Some tardigrades are able to survive exposure to extreme heat, cold, pressure, radiation, and lengths of time without water. One of their mechanisms for survival is called a “tun state,” in which they release all of the water from their bodies and lower their metabolisms to .01%. They can remain in this state for decades, only reanimating themselves when they come into contact with water again.

TardigradeAlso known as “water bears” or “moss piglets,” tardigrades are widely known for their ability to survive even after being exposed to outer space, as well as for being some of the cutest microorganisms. Some tardigrades are able to survive exposure to extreme heat, cold, pressure, radiation, and lengths of time without water. One of their mechanisms for survival is called a “tun state,” in which they release all of the water from their bodies and lower their metabolisms to .01%. They can remain in this state for decades, only reanimating themselves when they come into contact with water again. -

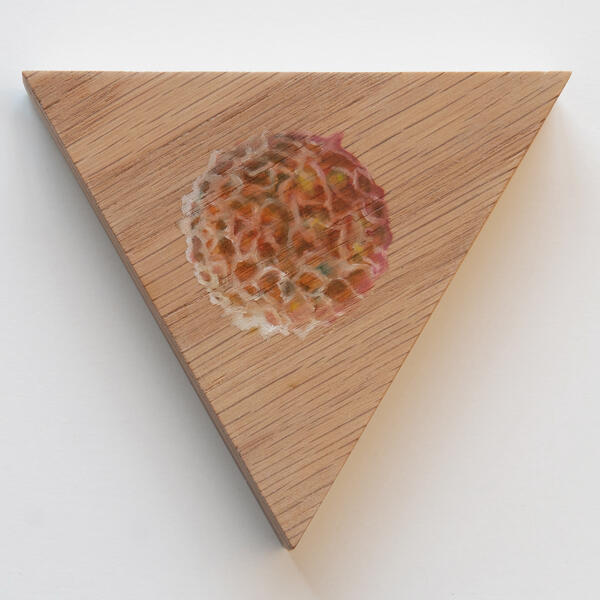

RadiolarianRadiolarians are a type of single-celled zooplankton which construct intricate, symmetrical shells out of silica. These shells serve not only as protection, but also as a ballast to balance the organisms as they float through the water. Some of the earliest eukaryotes to evolve, they are found in oceans throughout the planet today and dating back 500 million years to the Cambrian era. As zooplankton, they are an important part of the base of the food web. They are valuable in the fossil record because their silica shells do not dissolve in acids, and can remain intact at the bottom of the sea bed for millions of years. Radiolarians were the original inspiration for Ernst Haeckel to knit together his love of science and art. He was one of the earliest scientists to study them, discovered and named over 100 new species, and created thousands of drawings and paintings of them.

RadiolarianRadiolarians are a type of single-celled zooplankton which construct intricate, symmetrical shells out of silica. These shells serve not only as protection, but also as a ballast to balance the organisms as they float through the water. Some of the earliest eukaryotes to evolve, they are found in oceans throughout the planet today and dating back 500 million years to the Cambrian era. As zooplankton, they are an important part of the base of the food web. They are valuable in the fossil record because their silica shells do not dissolve in acids, and can remain intact at the bottom of the sea bed for millions of years. Radiolarians were the original inspiration for Ernst Haeckel to knit together his love of science and art. He was one of the earliest scientists to study them, discovered and named over 100 new species, and created thousands of drawings and paintings of them.

Sky Portals (2019)

Some of my most memorable and uplifting experiences involve watching clouds. Sometimes it’s been through a plane window, or through binoculars. Once I witnessed evening clouds through James Turrell's "Skyspace" in Sweden. But mostly it’s been from the ground with bare eyes. As an avid cloud watcher, I am drawn to the infinite variations in shape and color those magical tufts of water vapor can embody. Cloud forms are a challenge to replicate because of the way light interacts with them, their hard and soft edges, and their inconsistent shapes. They are simultaneously insubstantial and substantial. As a painter I strive to capture color, light, and form; using clouds as a subject gives me free range to play with all of those qualities. Clouds are complex, vital, and a defining characteristic of our Earth. These Sky Portals exist as a tribute to the fleeting moments of beauty that our skies provide.

Ceramics

Since 2019 I have been experimenting with functional ceramics, often carved with textures inspired by the same natural sources my 2D work draws from.