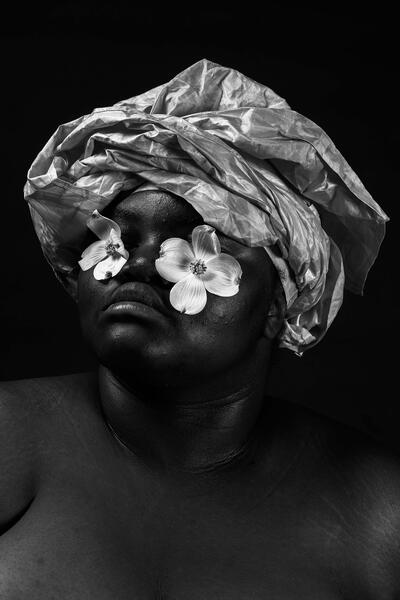

I immigrated to the United States from the Democratic Republic of Congo at the age of 9, because of this, I have experienced the gradual loss of familial and cultural connections. My lingala and Tshiluba slowly but surely trading phrases, words, letters with English ones. There’s now this existing barrier that strips me of my identity, not only turning me into an observer but limiting my participation within this culture. I find myself grieving as I am now in constant recalling of things I cannot name, people, family–I cannot remember, smells, tastes, I cannot find. I rely on contradicting memories and American forums in an attempt to rebuild my identity as a Congolese woman. Even, conversations between my mother and I can barely be held together without the use of online translators. I have now been on American soil longer than the DRC wrestling with longing, regret and shame for this loss. In my work, I am transfiguring my guilt into honesty as I grasp at whatever memories remain. I am building a space where the broken French is broken, but at least it’s said. I am revitalizing my assimilated identity.

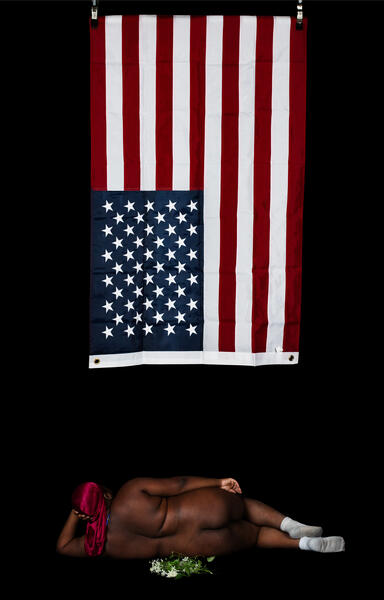

My work contains ideas of grief and retrieval. Here, memories of my home country are lost until I find them again. Represented through American and/or Congolese Iconographies and symbols such as a large overwhelming American flag, a dripping water jug, and denim, etc.

Nudity is another element that frequents my work, a vulnerability that can only be shown through the lens. I utilize these elements to further drive the ideas of how relentless and tiresome American culture imposes itself upon you, resulting in nothing but loss. All of these ideas come together to not only critique but to reject and denounce American Imperialism within this black body. Through my works, I grieve, I seek, I acknowledge the space I now take up within my Congolese identity. But you must remember, this is not a burial, this is a journey back home.