Work samples

-

Kangerlussuaq: Cold War, Warming Climate

Kangerlussuaq: Cold War, Warming ClimateGreenland Ice Sheet in Midsummer (2022) Part of my project concerns "the journey of ice and water" from the ice sheet that covers 80% of Greenland and downriver 20 miles to the Kangerlussuaq Fjord from which it eventually flows into the ocean. Streams of meltwater form on the surface of the ice in midsummer. This is a natural process, but there has been an increased rate of melting since 2000 is due to climate change, and the impact is visible at the edge of the ice in Kangerlussuaq which has retreated inland about a half-mile since then.

-

Kangerlussuaq: Cold War, Warming Climate

Kangerlussuaq: Cold War, Warming ClimateAirport Signpost (2021) and Andreas Lund-Drosvad with Signpost (unknown photographer, 1959) Part of my project includes locating vintage photos in archives and rephotographing the same sites. Here Kangerlussuaq’s iconic red and white signpost originally stood in front of the former civilian hotel before being relocated to the airport. In 2014 the signpost was renovated by Air Greenland, changing the flight times, adding cities, and removing the SAS company emblem from the top. Andreas “Suko” Lund-Drosvad (1899-1989) posed with the sign in 1959. He moved to Greenland from Denmark in the 1920s and established a museum in the town of Upernavik.

-

Kangerlussuaq: Cold War, Warming Climate

Kangerlussuaq: Cold War, Warming ClimateMock Airplane Crash for Firefighter Training (2022). I am currently working on a photo book project exploring the remote Arctic town of Kangerlussuaq, Greenland, a former indigenous hunting ground that has been reshaped by its highly unusual geopolitical history and the impact of climate change, including as a US Cold War Air Base from 1941 to 1992. The base closed in 1992 but the town and environs are dominated by its infrastructure, including repurposed and abandoned buildings and vast quantities of obsolete equipment left behind. Not all the old military junk ends up in the junkyard. On the outskirts of town, this assemblage of an old fuel tank, barrels, ladders, and scrap lumber serves as a mock airplane crash periodically set ablaze for firefighter training.

-

Kangerlussuaq: Cold War, Warming Climate

Kangerlussuaq: Cold War, Warming ClimateKangerlussuaq Junkyard (2022). The Kangerlussuaq junkyard is an astonishing place, a semi-organized conglomeration of the discarded appliances and household items you'd see in any town dump alongside decades-old relics of the US military base that closed 30 years ago: obsolete vehicles and machinery and piles of wood utility poles, barrels, and scrap metal.

About Helen

As an artist, I focus attention on places that are often overlooked or inaccessible, capturing the remarkable variety of ways that wind and water shape the landscape. My photographs and photo-based sculptures take you on a journey through these spaces and illuminate the interacting forces affecting environments and ecosystems, including human activity, from the remote polar environments of Antarctica… more

The Journey of Ice Part 1 from "Kangerlussuaq: Cold War, Warming Climate"

I am currently working on a photo book project exploring the remote Arctic town of Kangerlussuaq, Greenland, a former indigenous hunting ground that has been reshaped by its highly unusual geopolitical history and the impact of climate change. I collaborated with the Kangerlussuaq Museum, which received funding from the US Embassy in Copenhagen to redo two rooms with a permanent exhibit of my photographs and one sculpture. One room follows "The Journey of Ice" showing places along the approximately 20-mile river fed by the melting ice cap to the site of the town at mouth of the fjord. The 10 photos shown here focus on the ice cap and glaciers that flow off of it. They include a vintage photograph from the 1950s of one of the sites, the Russell Glacier, which shows the effects of climate change when compared to my photos at that site.

The isolated town of 500 people at the end of a 118-mile-long fjord was founded as a US air base that operated 1941-92. In 1999, German automakers built a road to the ice cap covering 80% of Greenland for a short-lived failed project to test drive cars on ice. The effects of climate change are starkly visible at the road's end, formerly the ice cap edge, now a long gravel slope uncovered by melting ice. The book will explore the past 80 years of the impact of human interventions in the environment: military, corporate, scientific, and global climate change. Compelling visual images bring home the seriousness of the climate change problem and the urgency of confronting it now.

-

Greenland Ice Sheet

Greenland Ice Sheet(2021) Standing on the ice sheet that covers 80% of Greenland, looking inland. Photo taken in mid-September after several days of freezing temperatures and a snowfall of a few inches froze the meltwater streams.

-

Ice Cap at Point 660, Midsummer

Ice Cap at Point 660, Midsummer(2022) The edge of the Greenland ice cap in midsummer when streams of meltwater form between the mounds of ice. Gravel blown onto the icy crust makes this image resemble a pencil drawing.

-

Tour Group Walking on the Ice, Point 660

Tour Group Walking on the Ice, Point 660(2022) The road’s end, known as Point 660, provides a benchmark for the effects of climate change. In 2001 when the auto testing project was active, vehicles could drive directly onto the ice cap from the end of the road. Now visitors walk down the steep gravel hill formerly covered by the ice cap in the foreground of this photograph. As the ice sheet melts and its edge recedes inland, it also uncovers permafrost (a layer of soil that is frozen year round). A print of this photograph is in the permanent installation at the Kangerlussuaq Museum.

-

Retreating Edge of the Greenland Ice Cap, Point 660

Retreating Edge of the Greenland Ice Cap, Point 660(2022) 20 years ago, the ice cap that covers 80 percent of Greenland also covered the steep moraine on the left. The ice has since retreated inland. (A regional government official told me that the ice formerly covering the moraine has dropped 30 to 50 meters since then.) In July, a swiftly flowing stream filled by meltwater from the ice cap divided the ice cap edge from the melting permafrost of the moraine.

-

Russell Glacier Panorama

Russell Glacier Panorama(2022) The Russell Glacier flows off the Greenland ice cap. The Danish Arctic Institute has photographs from the 1950s taken by glaciologist Borge Fristrup (see next image), who conducted research there over several season. The photos show that the face of the glacier has eroded considerably since then and the height has noticeably dropped. They are both in the permanent installation at the Kangerlussuaq Museum to show the impact of climate change on this local landmark.

-

The Russell Glacier in 1955

The Russell Glacier in 1955(1955) The Russell Glacier flows off the Greenland ice sheet. Its front is located 25 km east of Kangerlussuaq. When my 2022 photograph is compared with one taken by Danish glaciologist Børge Fristrup in 1955 one sees the ice loss over those decades. Fristrup (1918-1985) participated in and led a number of scientific expeditions iand played a major role in investigations of the Greenland ice sheet. (Fristrup photo courtesy Danish Arctic Institute). A comparison of these two images is part of the permanent installation at the Kangerlussuaq Museum.

-

Waterfall at the Russell Glacier

Waterfall at the Russell Glacier(2023) Meltwater flowing off the Greenland ice cap gathers force as it enters the river that flows past the Russell Glacier, which is part of the ice cap, eroding a cave that has been rapidly enlarging in the past few years.

-

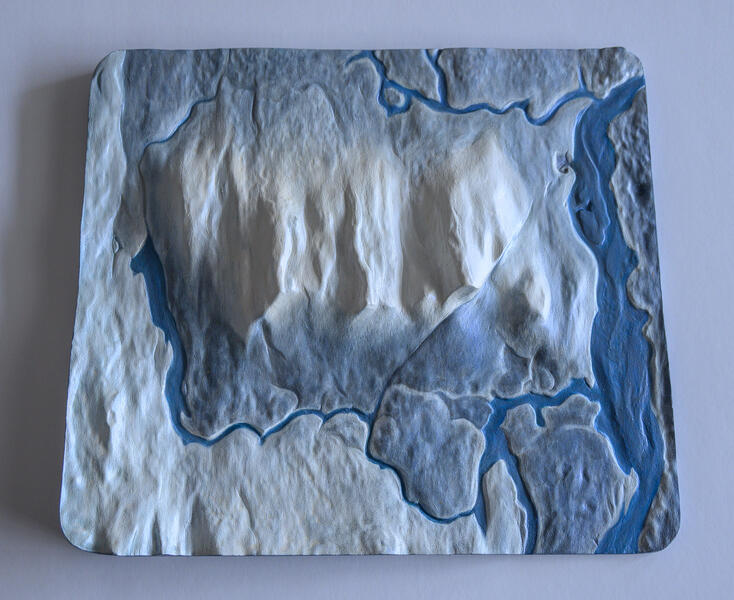

Site of the 3D scan of the ice cap

Site of the 3D scan of the ice cap(2022) Panoramic photo of the site where I made the 3D scan of the ice cap for the sculpture shown in the next image.

-

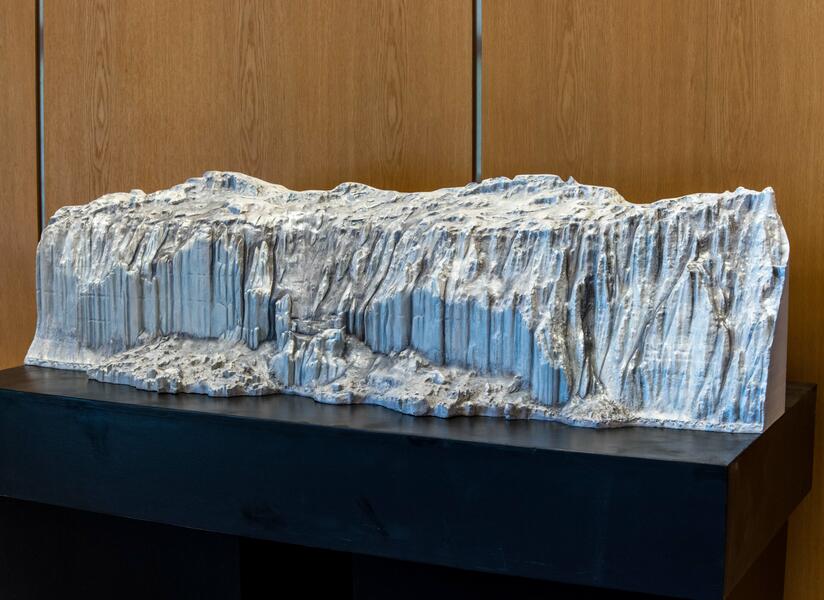

Greenland Ice Cap in Midsummer

Greenland Ice Cap in Midsummer(2023). This sculpture was made from a 3D scan of a small section of the ice cap near Point 660 for the permanent installation at the Kangerlussuaq Museum. The dark blue represents the streams of water that had formed under the summer sun. To make the sculpture, first a series of photographs of the scene from different angles were processed into a 3D file using photogrammetry software. After editing the file with 3D modeling software, it was carved in high density urethane foam by a machine that can read 3D files. Since the ice is constantly changing — and melting — this is a permanent record of a temporary form.

-

Permafrost Cracks, Point 660

Permafrost Cracks, Point 660(2022). 20 years ago, this rocky area crossed by visitors to Point 660 to walk onto the ice cap was covered by the ice sheet. As the ice sheet melts and its edge recedes inland, it uncovers the permafrost (a layer of soil that is frozen year round) to the sun. Without its cover of white ice to reflect the sun’s rays, the dark soil absorbs heat, melting the permafrost, so large cracks have now developed, exposing once-buried ice. Streams of meltwater run through these cracks in the summer.

The Journey of Ice Part II from "Kangerlussuaq: Cold War, Warming Climate"

I am currently working on a photo book project exploring the remote Arctic town of Kangerlussuaq, Greenland, a former indigenous hunting ground that has been reshaped by its highly unusual geopolitical history and the impact of climate change. I collaborated with the Kangerlussuaq Museum, which received funding from the US Embassy in Copenhagen to redo two rooms with a permanent exhibit of my photographs and one sculpture. One room follows "The Journey of Ice" showing places along the approximately 20-mile river fed by the melting ice cap to the site of the town at mouth of the fjord. The 10 photos shown here focus on the ice cap and glaciers that flow off of it. They include a comparison between two photographs I a section of the ice cap that locals call the "Reindeer Glacier" that shows considerable ice loss between 2018 and 2022. I took the 2018 photo on my initial visit to Kangerlussuaq, a one-day stop on a tour of West Greenland, which is how I came to know about it and see it as the subject for a potential long-term project in the first place.

The isolated town of 500 people at the end of a 118-mile-long fjord was founded as a US air base that operated 1941-92. In 1999, German automakers built a road to the ice cap covering 80% of Greenland for a short-lived failed project to test drive cars on ice. The effects of climate change are starkly visible at the road's end, formerly the ice cap edge, now a long gravel slope uncovered by melting ice. The book will explore the past 80 years of the impact of human interventions in the environment: military, corporate, scientific, and global climate change. Compelling visual images bring home the seriousness of the climate change problem and the urgency of confronting it now.

-

Waterfall from the Ice Cap to the River(2022) Meltstreams off the ice cap in summer collect here and flow down a waterfall and into the river that winds some 19 miles to the mouth of the fjord.

Waterfall from the Ice Cap to the River(2022) Meltstreams off the ice cap in summer collect here and flow down a waterfall and into the river that winds some 19 miles to the mouth of the fjord. -

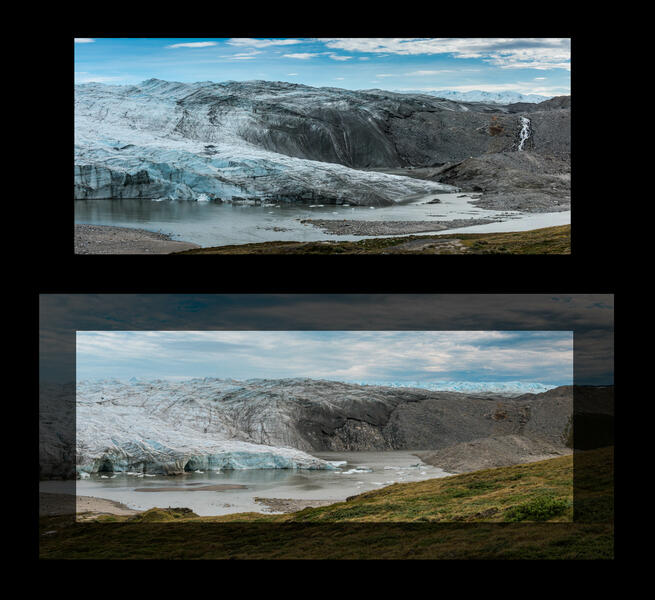

Reindeer Glacier Ice Loss Between 2018 and 2022

Reindeer Glacier Ice Loss Between 2018 and 2022Photographs taken on my first visit to Kangerlussuaq (a one-day visit as part of a tour in 2018, top) and when I returned four years later (bottom) show the extent of the ice loss over that period, in terms of the overall elevation of the ice, the portion extending into the river, and the portion over the dark gravel hill on the right. "Reindeer Glacier" is the local nickname for this portion of the ice cap. These photographs are part of the permanent installation at the Kangerlussuaq Museum.

-

Akuliarusiarsuup Kuua and Sugarloaf(2022) The Akuliarusiarsuup Kuua is a river of meltwater from the Greenland ice cap, some 20 miles to the east.

Akuliarusiarsuup Kuua and Sugarloaf(2022) The Akuliarusiarsuup Kuua is a river of meltwater from the Greenland ice cap, some 20 miles to the east. -

Kangerlussuaq Panorama from Black Ridge

Kangerlussuaq Panorama from Black Ridge(2022) A panorama of the town from the top of Black Ridge (elev. 360 feet), a hill overlooking the confluence of the river from the ice cap and the fjord leading out to sea (located where the bridge is). Most of the buildings were originally built by the American military which also blasted two channels beneath where the bridge is now so the area around the shore wouldn't flood during the summer melt season. The sites shown in the next 5 photographs can all be seen from right to left in this panorama, following the direction of the river flow. This photograph is part of the permanent installation at the Kangerlussuaq Museum.

-

Glacial Silt, Riverbank

Glacial Silt, Riverbank(2022) A close-up of the wave-like patterns of silt on the rocks just before the town bridge where the river empties into the Kangerlussuaq Fjord. The river is fed by melting of the Greenland ice cap flowing off the Russell Glacier, which in the summer months is milky with fine glacial silt. As one scientist puts it, "By the time it gets to Kangerlussuaq and passes under the town’s bridge, it’s essentially a rock, soil, and sand smoothie."

-

Stone Sorter, "Dust City"(2022) During the days of the Sondrestrom Air Base, soldiers called the broad sandy riverbank next to the town "Dust City." This vintage stone sorter and two other nearby pieces of equipment were used by the base — and still sometimes today — for sifting gravel for road repair.

Stone Sorter, "Dust City"(2022) During the days of the Sondrestrom Air Base, soldiers called the broad sandy riverbank next to the town "Dust City." This vintage stone sorter and two other nearby pieces of equipment were used by the base — and still sometimes today — for sifting gravel for road repair. -

2022-0731-39.jpg

2022-0731-39.jpgThe American military blasted two channels beneath where the bridge is now so the area around the shore wouldn't flood during the summer melt season. It has altered the ecology so that more silt flows into the fjord, so that where once there was a pier where boats could dock near town, the water is now too shallow. This photograph is on a two-page spread in the book The New Geologic Epoch (ecoartspace, 2023).

-

2021-0927-114-ED.jpg

2021-0927-114-ED.jpg(2021) Every summer, the soupy mix of melted ice and fine glacial silt from the Greenland ice sheet settles in the fjord after passing beneath the town bridge. Here, as autumn arrives, the water level decreases, revealing semi-frozen mud — and quicksand. This photograph is part of the permanent installation at the Kangerlussuaq Museum.

-

Glacial Silt, Kangerlussuaq FjordA close-up of the wave-like patterns of silt on the rocks where Qinnguata Kuussua (also known as Watson River) empties into the Kangerlussuaq Fjord after passing through a channel in the rock blasted by the American military, spanned by a bridge. The river is fed by melting of the Greenland ice cap flowing off the Russell Glacier, which in the summer months is milky with fine glacial silt. As one scientist puts it, "By the time it gets to Kangerlussuaq and passes under the town’s bridge, it’s essentially a rock, soil, and sand smoothie."

Glacial Silt, Kangerlussuaq FjordA close-up of the wave-like patterns of silt on the rocks where Qinnguata Kuussua (also known as Watson River) empties into the Kangerlussuaq Fjord after passing through a channel in the rock blasted by the American military, spanned by a bridge. The river is fed by melting of the Greenland ice cap flowing off the Russell Glacier, which in the summer months is milky with fine glacial silt. As one scientist puts it, "By the time it gets to Kangerlussuaq and passes under the town’s bridge, it’s essentially a rock, soil, and sand smoothie." -

Rocks and Rebar, Kangerlussuaq Fjord(2021) Looking down on the eroded rocks beneath the bridge where the river flowing from the Greenland ice cap some 20 miles away empties into the fjord. A piece of rebar is embedded in the rock, possibly from one of the earlier bridges this one replaced.

Rocks and Rebar, Kangerlussuaq Fjord(2021) Looking down on the eroded rocks beneath the bridge where the river flowing from the Greenland ice cap some 20 miles away empties into the fjord. A piece of rebar is embedded in the rock, possibly from one of the earlier bridges this one replaced.

Legacy of the US Air Base from "Kangerlussuaq: Cold War, Warming Climate"

I am currently working on a photo book project exploring the remote Arctic town of Kangerlussuaq, Greenland, a former indigenous hunting ground that has been reshaped by its highly unusual geopolitical history and the impact of climate change. Part of the project focuses on the vestiges of the American Sondrestrom Air Base (1941-1992) that dominate the town's landscape. The exhibit I am currently planning with the Kangerlussuaq Museum and my planned photo book will include comparisons between vintage photos of the base in the collections of the Danish Arctic Institute and US National Archives, from research I have done. Examples of those are shown here.

This isolated town of 500 people at the end of a 118-mile-long fjord was founded as a US air base that operated 1941-92. Repurposed and abandoned buildings and obsolete machinery remain, as do thousands of musk oxen descended from 27 imported as a scientific experiment in 1962. In 1999, German automakers built a road to the ice cap covering 80% of Greenland for a short-lived failed project to test drive cars on ice. The effects of climate change are starkly visible at the road's end, formerly the ice cap edge, now a long gravel slope uncovered by melting ice. The book will explore the past 80 years of the impact of human interventions in the environment: military, corporate, scientific, and global climate change. Compelling visual images bring home the seriousness of the climate change problem and the urgency of confronting it now. My project also illuminates a little-known corner of American and European history related to their presence in the region and its lasting impact, as Greenlanders aspires to a postcolonial future independent of Denmark. This story intersects with environmental, political, and cultural identity issues that resonate with the experiences of other indigenous and colonized populations around the world — including within the US.

-

Base Commanders Office, Kangerlussuaq MuseumIn 1992, the American air base commander turned over the keys to the buildings to the local airport authorities and left the contents intact at their request, including his US military issue parka and the trophy musk ox head on the wall. It is preserved today in the town museum.

Base Commanders Office, Kangerlussuaq MuseumIn 1992, the American air base commander turned over the keys to the buildings to the local airport authorities and left the contents intact at their request, including his US military issue parka and the trophy musk ox head on the wall. It is preserved today in the town museum. -

2021-0928 + RS184472 Signpost Composite-2.jpg

2021-0928 + RS184472 Signpost Composite-2.jpgHelen Glazer Signpost, Kangerlussuaq Airport (2021)

Unidentifed photographer, Andreas Lund-Drosvad with Signpost (1959) (Collection Danish Arctic Institute)Kangerlussuaq’s iconic red and white signpost originally stood in front of this museum building, then the Danish Hotel before being relocated to the airport. In 2014 the signpost was renovated by Air Greenland, changing the flight times, adding cities, and removing the SAS company emblem from the top. Andreas “Suko” Lund-Drosvad (1899-1989) posed with the sign in 1959. He was came to Greenland in the 1920s and settled in Upernavik where he lived for many decades and established the Upernavik Museum. This pair of photographs is part of a permanent installation at the Kangerlussuaq Museum in a room devoted to my photographs juxtaposed with vintage photos of similar sites related to the town's history as a military and scientific research outpost.

-

Sondrestrom Offshore Transit Home(2021) The former Offshore Transit Home of the Sondrestrom Air Base is one of many abandoned military buildings I photographed. This one is in the part of town known as Old Camp, where barracks for Danish troops and facilities for the entire base were located. Dozens of disconnected telephone poles like the ones here are found throughout the base. (They were shipped here by the US military from outside Greenland which has no native trees that grow more than a few feet high.) They are gradually being cut down and added to a huge pile in the town junkyard.

Sondrestrom Offshore Transit Home(2021) The former Offshore Transit Home of the Sondrestrom Air Base is one of many abandoned military buildings I photographed. This one is in the part of town known as Old Camp, where barracks for Danish troops and facilities for the entire base were located. Dozens of disconnected telephone poles like the ones here are found throughout the base. (They were shipped here by the US military from outside Greenland which has no native trees that grow more than a few feet high.) They are gradually being cut down and added to a huge pile in the town junkyard. -

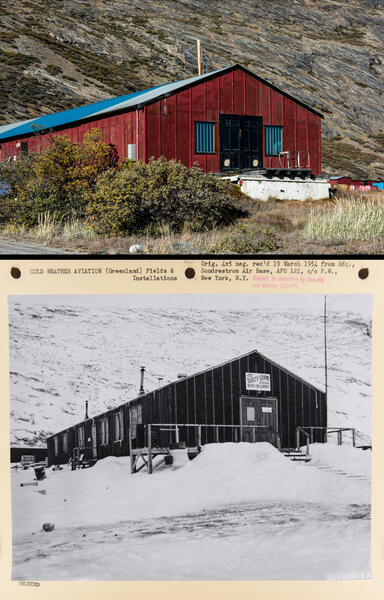

The Dirty Shame Saloon 2021 and 1954Part of my project involves rephotographing sites in old photos of the air base as they look today. My 2021 photograph of an abandoned building is shown here with a rephotographed 1954 mounted print from the U.S. National Archives when it was The Dirty Shame Saloon.

The Dirty Shame Saloon 2021 and 1954Part of my project involves rephotographing sites in old photos of the air base as they look today. My 2021 photograph of an abandoned building is shown here with a rephotographed 1954 mounted print from the U.S. National Archives when it was The Dirty Shame Saloon. -

Abandoned Hut Near the Russell GlacierIt's a mystery: Who transported this hut to an isolated patch of tundra across the river from the Russell Glacier in Kangerlussuaq — and why? Before posting it here I asked a Facebook group of American and Danish veterans of the former Sondrestrom Air Base and they didn't know either — men who were deployed as long ago as 1972 said they'd always wondered the same thing (one posted a 50-year-old photo of himself standing beside it). You can see in these photos that it has slid downhill from its original spot, and that the interior is covered with graffiti going back to the 1950s.

Abandoned Hut Near the Russell GlacierIt's a mystery: Who transported this hut to an isolated patch of tundra across the river from the Russell Glacier in Kangerlussuaq — and why? Before posting it here I asked a Facebook group of American and Danish veterans of the former Sondrestrom Air Base and they didn't know either — men who were deployed as long ago as 1972 said they'd always wondered the same thing (one posted a 50-year-old photo of himself standing beside it). You can see in these photos that it has slid downhill from its original spot, and that the interior is covered with graffiti going back to the 1950s. -

Kangerlussuaq Junkyard(2022) The Kangerlussuaq junkyard is an astonishing place, a semi-organized conglomeration of the discarded appliances and household items you'd see in any town dump alongside decades-old relics of the US military base that closed 30 years ago: obsolete vehicles and machinery; dozens of telephone poles, empty oil drums, and fuel tanks; and stacks of scrap metal. Missing from the US's agreement with Denmark authorizing the building of Greenland's Cold War bases in 1951 was a plan for disposing of anything brought in when it was no longer needed.

Kangerlussuaq Junkyard(2022) The Kangerlussuaq junkyard is an astonishing place, a semi-organized conglomeration of the discarded appliances and household items you'd see in any town dump alongside decades-old relics of the US military base that closed 30 years ago: obsolete vehicles and machinery; dozens of telephone poles, empty oil drums, and fuel tanks; and stacks of scrap metal. Missing from the US's agreement with Denmark authorizing the building of Greenland's Cold War bases in 1951 was a plan for disposing of anything brought in when it was no longer needed. -

Mock Airplane for Firefighter Training(2022) On the outskirts of town, an old fuel tank and barrels from the former American air base has been repurposed into a mockup of an airplane crash for firefighter training. (Most cities in Greenland are only connected by air or boat, so air travel into and out of the town's airport is constant throughout the day.)

Mock Airplane for Firefighter Training(2022) On the outskirts of town, an old fuel tank and barrels from the former American air base has been repurposed into a mockup of an airplane crash for firefighter training. (Most cities in Greenland are only connected by air or boat, so air travel into and out of the town's airport is constant throughout the day.) -

"Mickey Mouse" Decommissioned Radar DishesErected over 60 years ago, this pair of decommissioned Cold War era radar dishes and radio terminal building left behind by US military have become a landmark locals refer to as "Mickey Mouse," as in, "Follow the road past Mickey Mouse..." Before the dish technology became obsolete in the late 1980s, they served as relay antennae channeling all communications to and from scattered radar sites for the Distant Early Warning missile defense system that stretched across the Arctic from Greenland to Alaska. I have found photos of them from 1961 in the US National Archives.

"Mickey Mouse" Decommissioned Radar DishesErected over 60 years ago, this pair of decommissioned Cold War era radar dishes and radio terminal building left behind by US military have become a landmark locals refer to as "Mickey Mouse," as in, "Follow the road past Mickey Mouse..." Before the dish technology became obsolete in the late 1980s, they served as relay antennae channeling all communications to and from scattered radar sites for the Distant Early Warning missile defense system that stretched across the Arctic from Greenland to Alaska. I have found photos of them from 1961 in the US National Archives. -

Abandoned Generator Station Interior(2022) Interior of the abandoned generator building atop a hill near the Kangerlussuaq Harbor. The massive machines with interiors still coated with inky grease have sat unused for at least 30 years.

Abandoned Generator Station Interior(2022) Interior of the abandoned generator building atop a hill near the Kangerlussuaq Harbor. The massive machines with interiors still coated with inky grease have sat unused for at least 30 years. -

US Air Force Planes on Runway(2022) Four US Air Force planes parked on the Kangerlussuaq Airport runway in 2022. Although Sondrestrom Air Base closed in 1992, the New York Air National Guard, which flies transport planes in the Arctic and Antarctic, maintains a small presence there and still trains in Kangerlussuaq.

US Air Force Planes on Runway(2022) Four US Air Force planes parked on the Kangerlussuaq Airport runway in 2022. Although Sondrestrom Air Base closed in 1992, the New York Air National Guard, which flies transport planes in the Arctic and Antarctic, maintains a small presence there and still trains in Kangerlussuaq.

Wildlife and Sites for Science from "Kangerlussuaq: Cold War, Warming Climate"

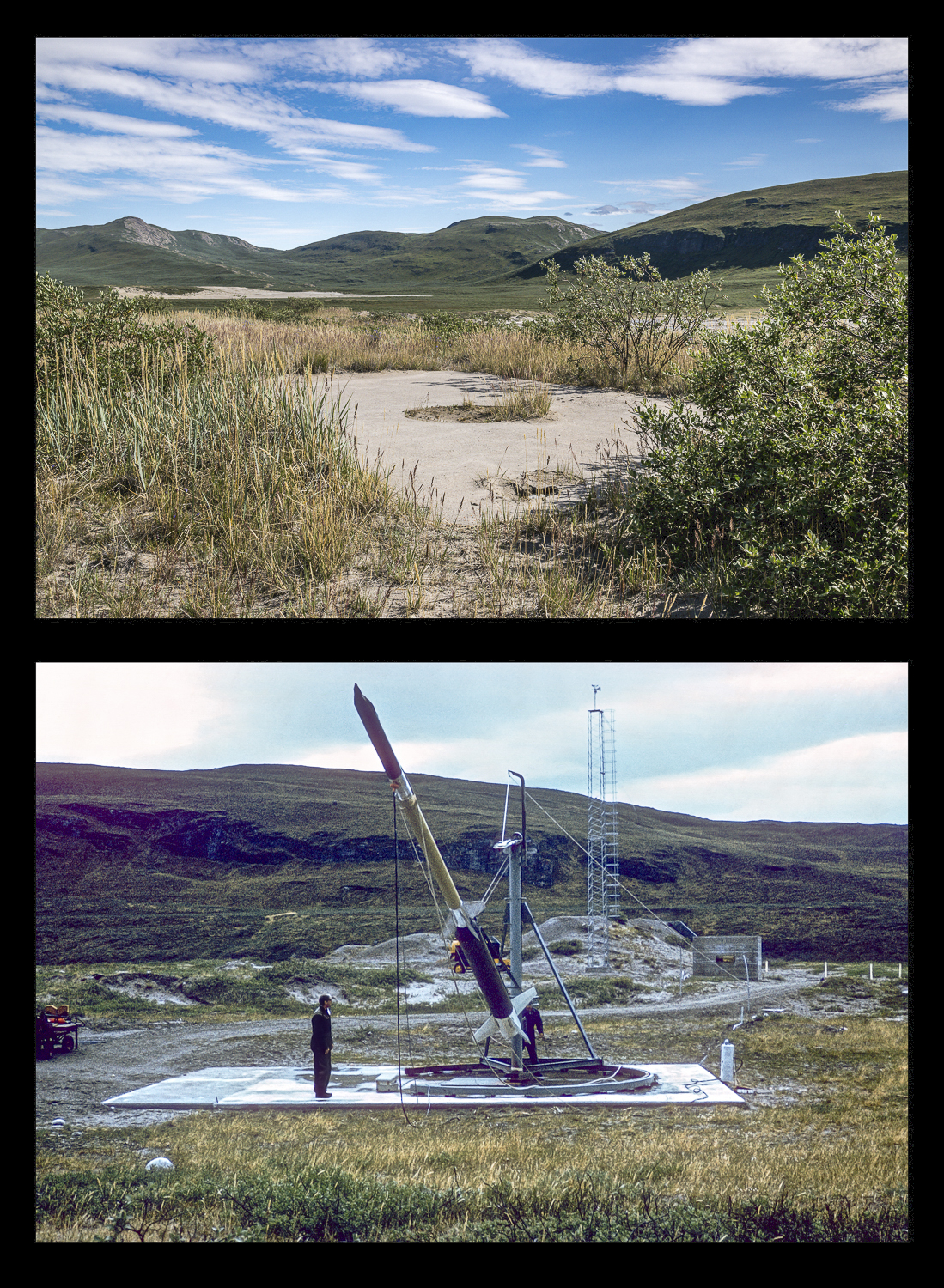

I am currently working on a photo book project exploring the remote Arctic town of Kangerlussuaq, Greenland, a former indigenous hunting ground that has been reshaped by its highly unusual geopolitical history and the impact of climate change. Kangerlussuaq has been a site for scientific research since the American meteorologist William Herbert Hobbs established a camp on a mountaintop near Kangerlussuaq Harbor from 1927 to 1929 to study the winds over Greenland. At the beginning of World War II, it was he who suggested Kangerlussuaq as an excellent location for an airfield, being far less likely to be fogged in than the rest of Greenland. The first airfield in Greenland was constructed for the Hobbs Expeditions on a natural clay plateau, which is still marked by rows of weathered plywood markers (though not the original ones). In 1971 the Danish Meteorological Institute launched rockets from concrete platforms beside the river east of town for study of the upper atmosphere; more than 30 rockets were launched from there until it closed in 1987. A historic marker placed on the road near the site in 2019 stated that "due to heavy erosion only two remain intact and visible today." But by 2022, I discovered that one had already fallen into the river and was jutting out of the collapsed bank. In 1982, a 32-meter tall antenna dish for was relocated from Alaska for ionospheric and atmospheric research not far from Hobbs' original camp. It has stood unused since 2018, surrounded by boarded up buildings where researchers formerly lived and worked until 2023, when a Canadian university research group removed the old buildings with plans to construct new ones and reactivate the antenna.

Not far from the rocket launch site are a number of scattered conifers and birch trees, the survivors of an unsuccessful effort by a Danish botanist in the late 1970s to see if it was possible to introduce trees from other northern locations. (Trees generally don't grow more than two to four feet high in this cold climate.) By contrast, when a Danish biologist brought 27 musk oxen from East Greenland in an expensive and controversial effort to perpetuate the species in West Greenland, where there were no musk oxen, they thrived, and now an estimated 20,000 roam the surrounding hills. Musk oxen have become something of a Kangerlussuaq mascot (the annual summer half-marathon is called "The Running of the Musk Ox") and indigenous hunters have integrated the animals into their diet and the local economy. But there is also concern that their survival is threatened by inbreeding.

-

Caribou Pausing on a Rock

Caribou Pausing on a Rock(2022) A male Barren-ground Caribou (Rangifer tarandus groenlandicus) pauses on a flat rock in the hills above Kangerlussuaq on a summer evening. Members of the genus Rangifer are called caribou in North America and reindeer in Eurasia. Caribou are native to West Greenland and before the airbase, indigenous people would hike or travel by kayak from coastal settlements to hunt them during the summer months. Hunting caribou is still an important part of local culture, although the recently imported musk ox has also been added to the diet. This photograph is in the permanent installation at the Kangerlussuaq Museum.

-

Female Musk Ox

Female Musk Ox(2022) The thousands of musk oxen (Ovibos moschatus) roaming the hills surrounding Kangerlussuaq today are descended from just 27 calves brought here from East Greenland in the 1960s in an effort to perpetuate the species and establish them in West Greenland. This musk ox was with a herd grazing in the hills east of Lake Ferguson. It was a long day of hiking on spongy steep terrain until we quietly managed to creep around a small hill and hide behind a rock about 25 meters away. For a little over 15 minutes they tolerated our presence. This photograph is in the installation at the Kangerlussuaq Museum.

-

Running Musk Ox Bull

Running Musk Ox Bull(2022) The thousands of musk oxen (Ovibos moschatus) roaming the hills surrounding Kangerlussuaq today are descended from just 27 calves brought here from East Greenland in the 1960s in an effort to perpetuate the species and establish them in West Greenland. This musk ox was the male with a herd of females and calves in the hills east of Lake Ferguson. It was a long day of hiking on spongy steep terrain until my guide and I managed to sneak up to a small herd and hide behind a rock to photograph them. They tolerated our presence for about 15 minutes. The last one to come into view was the male, who looked up occasionally while grazing, then seemed to signal to the herd it was time to go by running toward them.

-

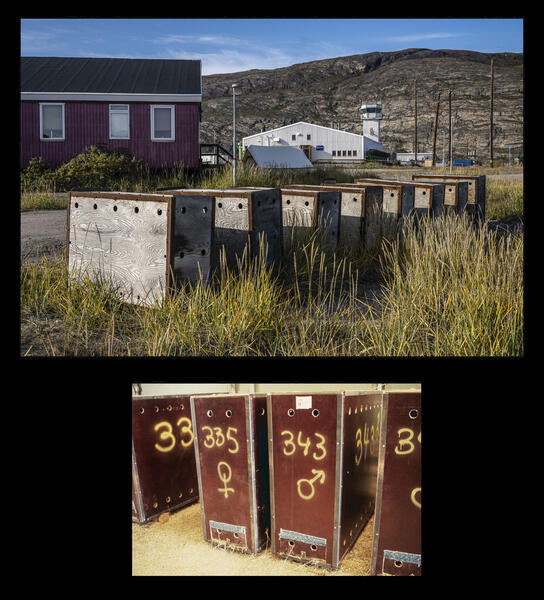

Helen-Glazer-12.jpg

Helen-Glazer-12.jpgHelen Glazer, Musk Ox Transport Crates, Kangerlussuaq Museum (2023)

Technical Sgt. Jose Hernandez, USAF, Musk Oxen Relocation Crates (1986) (US National Archives)27 musk oxen were introduced in Kangerlussuaq in the 1960s from East Greenland, where they are endemic, as an experiment by a Danish biologist. The effort was so successful that joint Denmark-US relocation operation to transport calves from Kangerlussuaq to re-establish a herd in Northwest Greenland was undertaken with the collaboration of the US Air Force and US Coast Guard. In 1986. In the bottom photo, storage containers for musk ox calves, numbered and identified male or female, were photographed before being loaded onto a US military transport plane. The crates were returned to Kangerlussuaq and stored on the edge of town until 2023, when they were moved behind the museum, which is also planning to redo a room for an exhibit devoted to musk oxen. The 1986 photo is installed next to my female musk ox photo at the Kangerlussuaq Museum.

-

Arctic Hare, Old Camp, Kangerlussuaq

Arctic Hare, Old Camp, Kangerlussuaq(2022) An Arctic hare (Lepus arcticus) springs from the bushes in Old Camp. Its summer coat of gray fur will turn white as winter approaches. This photograph is in the permanent installation at the Kangerlussuaq Museum.

-

Remnants of the Tree Experiment(2022) Scattered conifers and birch trees are the survivors of an unsuccessful effort by a Danish botanist to introduce trees from other northern locations. Their slender trunks and relatively small size bely the fact that they are 40 to 50 years old. In the background is a sign warning of the danger of unexploded ordnance in the area.

Remnants of the Tree Experiment(2022) Scattered conifers and birch trees are the survivors of an unsuccessful effort by a Danish botanist to introduce trees from other northern locations. Their slender trunks and relatively small size bely the fact that they are 40 to 50 years old. In the background is a sign warning of the danger of unexploded ordnance in the area. -

Sondrestrom Incoherent Radiation Radar

Sondrestrom Incoherent Radiation Radar(2022) Looking up at the intricate engineering of the Sondrestrom Incoherent Scatter Radar dish, built in 1971 for atmospheric research in Alaska, moved to Kangerlussuaq, Greenland in 1982, where it has stood unused since 2018. It was originally moved there because there was a hole in the ionosphere just above that area that makes it easier to gather information from space. In 2023, the surrounding buildings where science personnel lived and worked were torn down to make way for a Canadian university research groups that is planning to reactivate it. This photograph is in the permanent installation at the Kangerlussuaq Museum with a vintage 1984 photo of the radar dish complex, known locally as Kellyville after John Kelly, the scientist who initiated the project.

-

Site of Greenland’s First Airplane Runway

Site of Greenland’s First Airplane Runway(2022) Weathered triangular plywood markers weighted with rocks mark the outline of the site of Greenland’s first runway, originally prepared in 1928 on the Fossil Plains, a natural raised clay terrace alongside the Kangerlussuaq Fjord. The original runway served the University of Michigan Greenland Expedition, led by William Herbert Hobbs, which conducted meteorological research from a hilltop near Kangerlussuaq Harbor. This photograph is in the permanent installation at the Kangerlussuaq Museum.

-

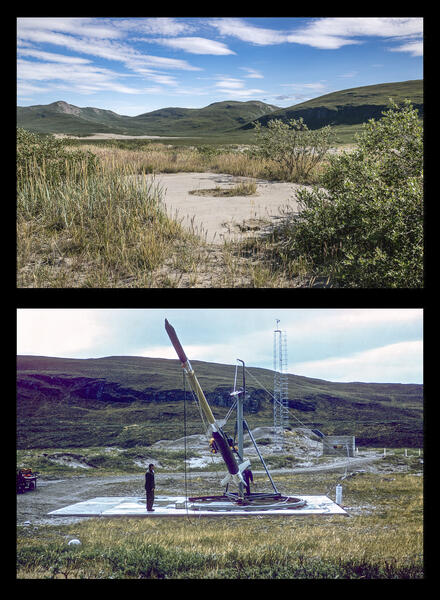

Helen-Glazer-13.jpg

Helen-Glazer-13.jpgHelen Glazer Rocket Launch Pad (2022)

Jørgen Taagholt Launch Pad with Rocket (1974) (Collection Danish Arctic Institute)In the 1970s, concrete rocket launch pads for meteorological experiments were installed east of the base along the shore of Akuliarusiarsuup Kuua. Increased water flow from the melting ice cap have heavily eroded the banks in this section of the river, leading to the collapse of all but one of the original platforms into the river. The 2022 photo shows the only remaining platform on land. A historical marker placed on the roadside in 2019 states that two of these rocket launch pads remain, but the next photograph shows one that by 2022, one had fallen into the river. These photographs are in the permanent installation at the Kangerlussuaq Museum.

-

Collapsed Bank and Rocket Launch Platform

Collapsed Bank and Rocket Launch Platform(2022) In the 1970s, concrete rocket launch platforms for meteorological experiments were installed along the shore of Akuliarusiarsuup Kuua, a river of meltwater that flows from the Greenland ice cap. The heavily eroded banks in this section of the river is evidence of how increased melting due to climate change has resulted in increased water flow, leading to the collapse of all but one of the original platforms into the river. A historical marker placed on the roadside in 2019 states that two of these rocket launch pads remain, but the next photograph shows one that by 2022, one had fallen into the river. In 2022, I found this one jutting out of the river. The preceding image shows a photo from 1974 of one of the experiments and the last remaining platform on land.

Toward a Post-Colonial Greenland from "Kangerlussuaq: Cold War, Warming Climate"

My first brief stay in Kangerlussuaq in August 2018 was for 24 hours, the final stop on an educationally oriented cruise in the Canadian Arctic and Greenland. It quickly became obvious that Kangerlussuaq differed from the typical Greenlandic towns we had visited, coastal fishing communities with colorful houses perched above a harbor filled with small boats. This impression was confirmed by a visit to the Kangerlussuaq Museum, which presented the military and aviation history in dozens of old photos and artifacts housed in the former American base commander's headquarters. Constrained by the itinerary of the group, I could not linger long at any one place. Nevertheless, I recognized Kangerlussuaq as a site combining two themes that I had explored in two prior projects: how human activity and infrastructure become part of a site's ecology, and the geological features of polar environments. The various foreign entities that had come through and left their mark on this patch of tundra over the past 80 years suggested to me a rich topic in terms of the cultural dimensions of landscape. Even the melting of the ice sheet due to global climate change caused by industrialized nations burning fossil fuels could be seen as an indirect foreign intervention.

As an American who grew up during the Cold War, I remember the weekly civil defense sounding of the town air raid siren at 1 p.m. every Monday, and being taught there was a Defense Early Warning system (DEW line) that stretched across the Arctic in case the Soviet Union fired a missile over the North Pole toward North America. But to learn on that 2018 visit of the large American presence at this location in Greenland where some 1,400 base personnel lived came as a surprise. The location of the runway was originally chosen as a refueling stop for planes supplying the European theater in World War II because it offered more clear days for flying than elsewhere in Greenland. The Cold War led to the base's expansion and that infrastructure made possible the landscape interventions that followed: the musk ox importation, the road to the ice sheet and auto testing project, and the establishment of Kangerlussuaq as Greenland's hub for international scientists. Many peculiar details left from that history are unique to Kangerlussuaq — the empty JATO rocket fuel canisters with peeling "Explosive" stickers that serve as cigarette ashtrays outside every building in town, the guardrails constructed by cables strung through rows of empty oil barrels painted pink and yellow, the small area on the outskirts where scattered 50-year-old Alaskan conifers are the stunted survivors of an unsuccessful tree-planting experiment. But if the specifics are particular to this place, it's not the only place in the world where the scale and scope of the military junk left behind by a closed base astonishes. One unintended consequence of the agreement between Denmark and the US permitting the base construction is that no plan for its future removal was included. Today, massive berms support massive empty fuel storage tanks. Rows of now-useless wooden utility poles are gradually being chopped down and piled in the town junkyard, where they join tall colorful heaps of scrap metal.

And yet, Americans are generally viewed positively today. Greenlanders hold complicated feelings toward the Danes, who although Greenland is a semi-autonomous territory, still run their judicial, police and defense and fund half their governmental budget. In speaking with residents of Kangerlussuaq, Danish people living there often expressed an impatience with the ignorance of their fellow Danes about Greenland and patronizing and prejudicial stereotypes about Greenlanders. Dorthe Katrine Olsen, the museum director with whom I collaborated on the exhibition at the Kangerlussuaq Museum, whose family goes back generations in Sisimiut, which is part of the same region as Kangerlussuaq, was vice chair of a Truth and Reconciliation Commission that wrote a report a few years ago. She told me the legacy of trauma and forced relocation from the mid 20th century plays out today in families struggling with alcoholism and other dysfunction. Danish is still the language of the middle class and economic opportunity, even as Greenlanders are trying to center Greenlandic and recently officially replaced Danish with English as the second language taught in schools beginning in the primary grades.

The fishing industry represents 50% of Greenland's economy. By contrast, Kangerlussuaq's economy centers on the airport, which has been the country's international hub since the US allowed SAS to use it as a refueling stop in the 1950s until this year, when a new airport came online in Greenland's capital, Nuuk. In a country where the only way to travel between settlements is by boat or plane, the runway and infrastructure left behind by the Americans is regarded as a boon even if the massive empty steel fuel tanks, rusting barges in the harbor, and dilapidated wooden buildings that still dot the landscape have become like so many hulking white elephants. Kangerlussuaq's complex story resonates with that of other places, including in the US, where military bases took over traditional indigenous hunting grounds seen as "empty" land where "nobody lived." For these reasons, I believe the story holds relevance and interest for people outside of Greenland.

-

Project Mailbag, Bluie West 8 (1947)

Project Mailbag, Bluie West 8 (1947)James Evans, Project Mailbag, Bluie West 8 (US Air Force photo in US National Archives)

A grader is used to level and grade a runway at Bluie West 8 (Sondre Stromfjord), Greenland, 14 July 1947. I have located all the photographs of the former Sondrestrom Air Base in the US National Archives at College Park, Maryland, and scanned the negatives in order to match them with similar locations or subjects as they appear today as part of my photo book project.

-

RS201315-EDv2.jpg

RS201315-EDv2.jpgBent Helmudt (1950-51), Kangerlussuaq Looking Toward Black Ridge (Collection Danish Arctic Institute)

Unlike other Greenlandic towns that have been settled by Greenlanders for generations, no permanent residents lived in Kangerlussuaq until construction of Sondrestrom Air Base by the US Air Force began in the 1940s. The bottom photo, made by a conscript in the Royal Danish Navy living at the base, documents how it looked before it was significantly expanded in the 1950s and ‘60s.

-

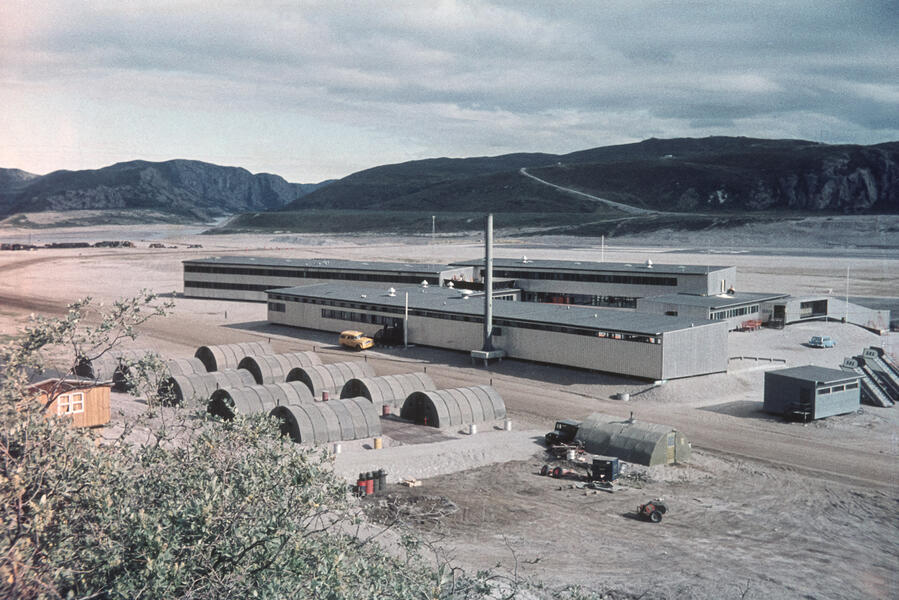

Airport Building and Military Barracks

Airport Building and Military BarracksJens Fabricius, Airport Building and Military Barracks (1961) (Collection Danish Arctic Institute)

The airport building has been altered and added to since 1961. Across the road once stood round-roofed Quonset huts housing soldiers at Sondrestrom Air Base. The next photo shows the same site today. Both this photo and the next one are hung together in the permanent installation at the Kangerlussuaq Museum.

-

2022-0731-85-ED.jpg

2022-0731-85-ED.jpg(2022) The airport building has been altered and added to since 1961. Across the road once stood round-roofed Quonset huts housing soldiers at Sondrestrom Air Base (see previous photo). Both this photo and the one from 1961 are hung together in the permanent installation at the Kangerlussuaq Museum.

-

2022-0724-134.jpg

2022-0724-134.jpg(2022) Erected over 60 years ago, this pair of decommissioned Cold War era radar dishes and radio terminal building left behind by the US military have become a landmark locals refer to as “Mickey Mouse,” as in, “Follow the road past Mickey Mouse...” Before dish technology became obsolete in the late 1980s, they served as relay antennae channeling communications to and from scattered radar sites as part of the Distant Early Warning missile defense system that stretched across the Arctic from Greenland to Alaska. I have located US National Archives photos of this installation taken in 1961.

-

2022-0727-229.jpg

2022-0727-229.jpg(2022) Disconnected wood utility poles, wires cut, still line long stretches of road, remnants of the former base. Gradually they are being cut down and hauled to the junkyard, where they are piled like oversized Lincoln Logs dumped from a box. Greenland largely lacks waste disposal and recycling facilities, so most of the base infrastructure remains.

-

2023-0916-36-2.jpg

2023-0916-36-2.jpg(2023) Tundra plants turned red and gold in September cling to a rock formation visible from a main road. In the 1980s American and Danish airmen referred to the black and white pattern lower right as "The Ayatollah" because they thought it resembled the turbaned Ayatollah Khomeini of Iran, who became notorious during the 444-day Iran Hostage Crisis in 1979-81.

-

Kangerlussuaq Cemetery from Black Ridge

Kangerlussuaq Cemetery from Black Ridge(2021) Before the American Air Base was established in 1941, Kangerlussuaq was an annual hunting ground for indigenous Greenlanders who lived on the coast some 80 to 120 miles away, but not a place with permanent structures that they identified as home. The establishment of the town cemetery in 2012 represented a shift. Surrounded by a white picket fence typical in Arctic villages in Greenland and Canada, as of 11 years later it had just nine graves decorated with artificial flowers, framed photos, lanterns, and other objects bordered by stones. The nearby dark circle was the former site of an air base fuel tank; beyond is an expanse of gravel and glacial silt dubbed "Dust City" during base days and still called that. Photographed from Black Ridge, a hill approximately 300 feet in elevation.

-

2022-0724-82.jpg

2022-0724-82.jpg(2022) Before the American Air Base was established in 1941, Kangerlussuaq was an annual hunting ground for indigenous Greenlanders who lived on the coast some 80 to 120 miles away, but not a place with permanent structures that they identified as home. The establishment of the town cemetery in 2012 represented a shift. Surrounded by a white picket fence typical in Arctic villages in Greenland and Canada, as of 11 years later it had just nine graves decorated with artificial flowers, framed photos, lanterns, and other objects bordered by stones.

-

2022-0718-73-2.jpg

2022-0718-73-2.jpg(2022) Empty JATO containers — which originally contained rocket fuel — are ubiquitous outside Kangerlussuaq buildings as outdoor ashtrays.

Walking in Antarctica: Sea Ice Formations

Walking in Antarctica consists of photographs, sculptures from 3D scans of geological formations, and a first-person audio tour, resulting from a seven-week residency in Antarctica in 2015 through the National Science Foundation Antarctic Artists and Writers Program.

The Erebus ice tongue is the end of a glacier that extends onto the sea ice on McMurdo Sound. A small opening in the tongue leads to an ice cave containing unusual and fragile ice crystal structures. It is accessible only a few weeks a year, in the company of a trained mountaineer from the US Antarctic Program, and I was extremely fortunate to visit it twice during my residency in late November and on December 1, 2015, first with a group and then with only myself the mountaineer. Shortly after that, the cave was closed for the season.

The crystals are lit by a lamp we brought inside. You enter the first chamber by sliding through a small opening and down a slight incline on your stomach. Some light filters in through the entrance. Further inside it is pitch black. I found that bouncing lights off the walls or backlighting the features brought them to life in a way that flash photography did not, so I directed the mountaineer to aim the light in different places as I took photographs.

Some of these photos were featured in an article on the Erebus Glacier ice tongue cave on the adventure travel web site AtlasObscura.com in early 2016. Two of them have also been enlarged to 7 x 10 feet and will be installed as part of a series of exhibitions by Maryland artists at BWI Marshall International Airport between June 2017 and June 2018. One was installed in a year-long outdoor exhibition of international artists at the Palacio de las Aguas, Buenos Aires, Argentina, that opened in 2023.

The sea ice pressure ridges were on different sections of McMurdo Sound. One was near New Harbor, accessed by a one-hour snowmobile ride from the biology dive camp where I spent a few days in the field. The other pressure ridge I photographed was at Scott Base, operated by the New Zealand Antarctic Program. Three months later, the Scott Base pressure ridges collapsed into the ocean and floated out to sea.

-

Cloudburst, Erebus Ice Tongue Cave, AntarcticaCloudburst, Erebus Ice Tongue Cave, Antarctica (2015), archival pigment print, 26.75 x 40 inches. Crystals hang from an interior ceiling just inside the cave entrance. The Erebus ice tongue is the end of a glacier that extends onto the sea ice on McMurdo Sound. A small opening in the tongue leads to an ice cave containing unusual and fragile ice crystal structures. It is accessible only a few weeks a year. Further inside, it is pitch dark, but just inside the opening, the ceiling had a blue glow, illuminated by sunlight filtering through the ice.

Cloudburst, Erebus Ice Tongue Cave, AntarcticaCloudburst, Erebus Ice Tongue Cave, Antarctica (2015), archival pigment print, 26.75 x 40 inches. Crystals hang from an interior ceiling just inside the cave entrance. The Erebus ice tongue is the end of a glacier that extends onto the sea ice on McMurdo Sound. A small opening in the tongue leads to an ice cave containing unusual and fragile ice crystal structures. It is accessible only a few weeks a year. Further inside, it is pitch dark, but just inside the opening, the ceiling had a blue glow, illuminated by sunlight filtering through the ice. -

Fractal Arch, Erebus Glacier Ice Tongue Cave(2015) photograph. I went in the ice cave with a mountaineer. When I had him bounce light or backlight the features it brought out a world of intricate, layered fractal patterns.

Fractal Arch, Erebus Glacier Ice Tongue Cave(2015) photograph. I went in the ice cave with a mountaineer. When I had him bounce light or backlight the features it brought out a world of intricate, layered fractal patterns. -

Gothic Ice, Backlit, Erebus Glacier Ice Tongue Cave(2015) photograph. I went in the ice cave with a mountaineer. When I had him bounce light or backlight the features it brought out a world of intricate, layered fractal patterns.

Gothic Ice, Backlit, Erebus Glacier Ice Tongue Cave(2015) photograph. I went in the ice cave with a mountaineer. When I had him bounce light or backlight the features it brought out a world of intricate, layered fractal patterns. -

"Stalactites," Erebus Glacier Ice Tongue Cave(2015) photograph. I went in the ice cave with a mountaineer. When I had him bounce light or backlight the features it brought out a world of intricate, layered fractal patterns.

"Stalactites," Erebus Glacier Ice Tongue Cave(2015) photograph. I went in the ice cave with a mountaineer. When I had him bounce light or backlight the features it brought out a world of intricate, layered fractal patterns. -

Blue Fractal, Erebus Glacier Ice Tongue Cave(2015) photograph. I went in the ice cave with a mountaineer. When I had him bounce light or backlight the features it brought out a world of intricate, layered fractal patterns.

Blue Fractal, Erebus Glacier Ice Tongue Cave(2015) photograph. I went in the ice cave with a mountaineer. When I had him bounce light or backlight the features it brought out a world of intricate, layered fractal patterns. -

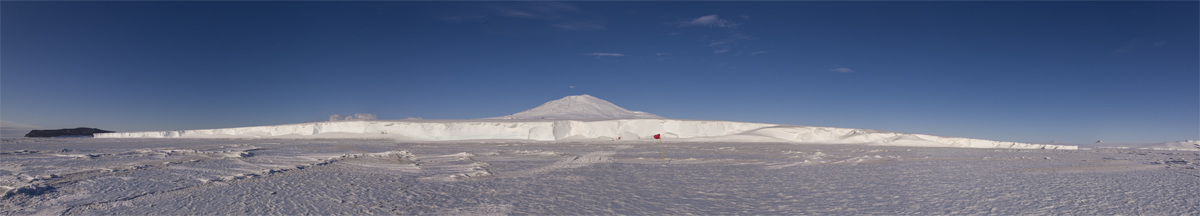

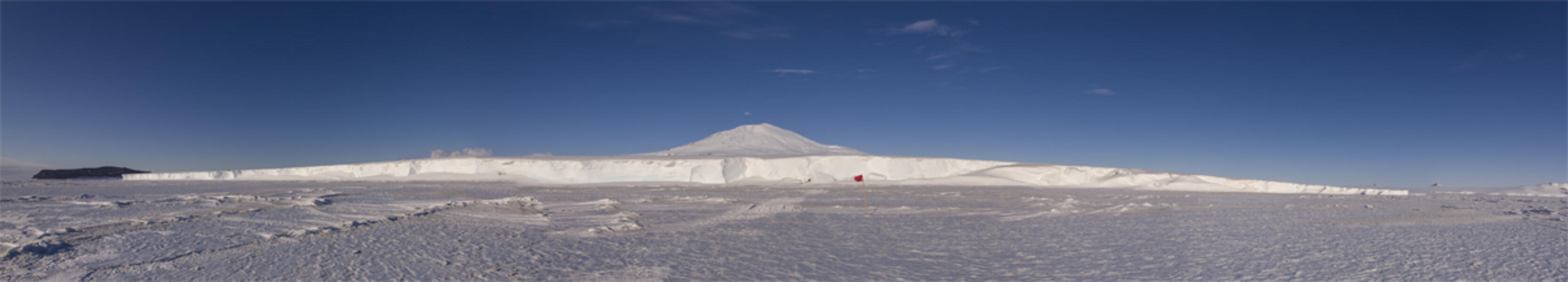

Erebus Ice Tongue Panorama, AntarcticaErebus Ice Tongue, Antarctica (2015) photograph. Photographed from the sea ice looking toward the entrance to the Erebus Ice Tongue cave is marked by a flagged path, roughly in the center of this panorama. In the background is Mt. Erebus, elevation 12,500 ft., the southernmost active volcano.

Erebus Ice Tongue Panorama, AntarcticaErebus Ice Tongue, Antarctica (2015) photograph. Photographed from the sea ice looking toward the entrance to the Erebus Ice Tongue cave is marked by a flagged path, roughly in the center of this panorama. In the background is Mt. Erebus, elevation 12,500 ft., the southernmost active volcano. -

Scott Base Pressure Ridge, AntarcticaScott Base Pressure Ridge, Antarctica (2015), photograph, 15 x 22.375 inches. This photo was taken from a hill overlooking the Scott Base pressure ridge. In the distance, on an ice shelf 7 miles away, you can barely make out the planes and buildings of the Williams Airfield, which serves the US and New Zealand bases.

Scott Base Pressure Ridge, AntarcticaScott Base Pressure Ridge, Antarctica (2015), photograph, 15 x 22.375 inches. This photo was taken from a hill overlooking the Scott Base pressure ridge. In the distance, on an ice shelf 7 miles away, you can barely make out the planes and buildings of the Williams Airfield, which serves the US and New Zealand bases. -

Scott Base Pressure Ridge, AntarcticaIcicles, Scott Base Pressure Ridge, Antarctica (2015) photograph, 15.25 x 22.375 inches. Close up of the pressure ridge, showing cantilevered ice pushed by tidal forces beneath the six-foot layer of sea ice. In the Antarctic summer, temperatures sometimes warmed to slightly above freezing, and the ice would melt and refreeze.

Scott Base Pressure Ridge, AntarcticaIcicles, Scott Base Pressure Ridge, Antarctica (2015) photograph, 15.25 x 22.375 inches. Close up of the pressure ridge, showing cantilevered ice pushed by tidal forces beneath the six-foot layer of sea ice. In the Antarctic summer, temperatures sometimes warmed to slightly above freezing, and the ice would melt and refreeze. -

Pressure Ridge Beneath the Double Curtain Glacier, AntarcticaPressure Ridge Beneath the Double Curtain Glacier, Antarctica (2015) photograph, 26.5 x 40 inches. The pressure ridges beneath the Double Curtain Glacier are seldom visited, as they are only accessible by an hour-long trip via snowmobile from the small New Harbor field camp, where I spent four days. This view overlooks the ridge, the sea ice, and the toe of the Ferrar Glacier in the distance.

Pressure Ridge Beneath the Double Curtain Glacier, AntarcticaPressure Ridge Beneath the Double Curtain Glacier, Antarctica (2015) photograph, 26.5 x 40 inches. The pressure ridges beneath the Double Curtain Glacier are seldom visited, as they are only accessible by an hour-long trip via snowmobile from the small New Harbor field camp, where I spent four days. This view overlooks the ridge, the sea ice, and the toe of the Ferrar Glacier in the distance. -

Rectangular Sea Ice, McMurdo Sound, AntarcticaRectangular Sea Ice, McMurdo Sound, Antarctica (2015), photograph, 12 x 18 inches. Photographed from a helicopter in mid-December, the surface of the sound has started to melt during the Antarctic summer, forming remarkably regular rectangular chunks surrounded by blue meltwater. In the distance are the Kukri Hills. The helicopter antennae is in the right foreground. This photograph is on view at the New York Hall of Science through February 2018.

Rectangular Sea Ice, McMurdo Sound, AntarcticaRectangular Sea Ice, McMurdo Sound, Antarctica (2015), photograph, 12 x 18 inches. Photographed from a helicopter in mid-December, the surface of the sound has started to melt during the Antarctic summer, forming remarkably regular rectangular chunks surrounded by blue meltwater. In the distance are the Kukri Hills. The helicopter antennae is in the right foreground. This photograph is on view at the New York Hall of Science through February 2018.

Walking in Antarctica: Antarctic Lake Ice

Walking in Antarctica consists of photographs, sculptures from 3D scans of geological formations, and a first-person audio tour, resulting from a seven-week residency in Antarctica in 2015 through the National Science Foundation Antarctic Artists and Writers Program.

Photographs of the unusual ice formations found in freshwater Antarctic lakes, which are fed by glaciers. These photographs were taken at Cape Royds and at Lake Hoare in the McMurdo Dry Valleys. Both areas are only visited by science teams and personnel supporting them. The Dry Valleys is a fragile environment and requires special permission to visit. I spent a week there, including five days at Lake Hoare, as a grantee of the National Science Foundation Antarctic Artists and Writers Program. My project was to photograph ice and geological formations in order to produce both archival pigment prints and three-dimensional artworks.

-

Skua, Lake Hoare, AntarcticaSkua, Lake Hoare, Antarctica (2015), photograph, 17 x 22.375 inches. This ice formation reminded me of a skua, a gull-like bird that was the only wildlife I saw during my stay in Antarctica, aside from seals and penguins.

Skua, Lake Hoare, AntarcticaSkua, Lake Hoare, Antarctica (2015), photograph, 17 x 22.375 inches. This ice formation reminded me of a skua, a gull-like bird that was the only wildlife I saw during my stay in Antarctica, aside from seals and penguins. -

Primary Ice, Lake Hoare, Antarctica(2015), photograph, 26.75 x 40 inches. Taken at about 1 a.m. under midnight sun, the lake surface is forming what is called "primary ice" in which crystals branch out, forming relief designs that were lit by the slanting sunlight. The designs remind me of Asian ceramics. The ice is framed by reflections of the Canada Glacier and the blue sky.

Primary Ice, Lake Hoare, Antarctica(2015), photograph, 26.75 x 40 inches. Taken at about 1 a.m. under midnight sun, the lake surface is forming what is called "primary ice" in which crystals branch out, forming relief designs that were lit by the slanting sunlight. The designs remind me of Asian ceramics. The ice is framed by reflections of the Canada Glacier and the blue sky. -

Loops and Layers, Lake HoareLoops and Layers, Lake Hoare (2015) photograph, 26.75 x 40 inches. Thin lake ice formations that formed over sediment that has blown onto the surface of the lake.

Loops and Layers, Lake HoareLoops and Layers, Lake Hoare (2015) photograph, 26.75 x 40 inches. Thin lake ice formations that formed over sediment that has blown onto the surface of the lake. -

Vapor Figures and Rainbow, Lake Hoare, AntarcticaVapor Figures and Rainbow, Lake Hoare, Antarctica (2015) photograph, 26.5 x 40 inches. The white etched designs are called Tyndall figures. This formation is richly textured with Tyndalls, frozen bubbles and a colorful interference pattern upper right.

Vapor Figures and Rainbow, Lake Hoare, AntarcticaVapor Figures and Rainbow, Lake Hoare, Antarctica (2015) photograph, 26.5 x 40 inches. The white etched designs are called Tyndall figures. This formation is richly textured with Tyndalls, frozen bubbles and a colorful interference pattern upper right. -

Oblongs, Cape Royds, AntarcticaOblongs, Cape Royds, Antarctica (2015) photograph, 26.75 x 40 inches. These rounded forms are embedded inside the ice. Glaciologists to whom I showed the photo thought maybe these were formed when a layer of water froze on top of scalloped surface ice, though they said the formations were unusual and unfamiliar.

Oblongs, Cape Royds, AntarcticaOblongs, Cape Royds, Antarctica (2015) photograph, 26.75 x 40 inches. These rounded forms are embedded inside the ice. Glaciologists to whom I showed the photo thought maybe these were formed when a layer of water froze on top of scalloped surface ice, though they said the formations were unusual and unfamiliar. -

Ice Ribbons, Lake Ice at Cape Royds, AntarcticaIce Ribbons, Lake Ice at Cape Royds, Antarctica (2015) photograph, 17 x 24 inches inches. These ribbon-like patterns appear embedded inside the ice of the lake a few feet from the shore. I found them at an inland lake at Cape Royds. I showed them to a group of glaciologists who were in Antarctica studying the sea ice. They were intrigued, though they could not explain the cause.

Ice Ribbons, Lake Ice at Cape Royds, AntarcticaIce Ribbons, Lake Ice at Cape Royds, Antarctica (2015) photograph, 17 x 24 inches inches. These ribbon-like patterns appear embedded inside the ice of the lake a few feet from the shore. I found them at an inland lake at Cape Royds. I showed them to a group of glaciologists who were in Antarctica studying the sea ice. They were intrigued, though they could not explain the cause. -

Algal Mat Origami, Cape Royds, Antarctica(2015) photograph, 16.75 x 24 inches or 28 x 40 inches. What looks like torn paper is algal mat that has dried and flaked over blue ice. The ice turns blue when all the air is compressed out of it.

Algal Mat Origami, Cape Royds, Antarctica(2015) photograph, 16.75 x 24 inches or 28 x 40 inches. What looks like torn paper is algal mat that has dried and flaked over blue ice. The ice turns blue when all the air is compressed out of it. -

Sand at Blood Falls, AntarcticaSand at Blood Falls, Antarctica (2015) photograph. The wet sand along the shore of Lake Bonney at Blood Falls was colored by striking shades of green and orange from mineral deposits that seep up and stain the ice.

Sand at Blood Falls, AntarcticaSand at Blood Falls, Antarctica (2015) photograph. The wet sand along the shore of Lake Bonney at Blood Falls was colored by striking shades of green and orange from mineral deposits that seep up and stain the ice. -

Bridge Onto Lake Hoare, AntarcticaBridge Onto Lake Hoare, Antarctica (2015) photograph, 22 x 14.675 inches. When the margin of Lake Hoare melts in the Antarctic summer, the scientists improvise bridges to get onto the ice. This is how I got to the areas I photographed on Lake Hoare for the other photographs of it in this set.

Bridge Onto Lake Hoare, AntarcticaBridge Onto Lake Hoare, Antarctica (2015) photograph, 22 x 14.675 inches. When the margin of Lake Hoare melts in the Antarctic summer, the scientists improvise bridges to get onto the ice. This is how I got to the areas I photographed on Lake Hoare for the other photographs of it in this set. -

Scallopped Sand, Lake Hoare, AntarcticaScallopped Sand, Lake Hoare, Antarctica (2015) photograph, 26.75 x 40 inches. Sand in the shadow of the Canada Glacier in Antarctica, a puddle in the center reflecting the clear blue sky of 24-hour daylight at 1:20 a.m.

Scallopped Sand, Lake Hoare, AntarcticaScallopped Sand, Lake Hoare, Antarctica (2015) photograph, 26.75 x 40 inches. Sand in the shadow of the Canada Glacier in Antarctica, a puddle in the center reflecting the clear blue sky of 24-hour daylight at 1:20 a.m.

Walking in Antarctica: Antarctica in 3D - Sculptures and Source Photos

Walking in Antarctica consists of photographs, sculptures from 3D scans of geological formations, and a first-person audio tour, resulting from a seven-week residency in Antarctica in 2015 through the National Science Foundation Antarctic Artists and Writers Program.

Sculptures based on photographs I took in Antarctica as a grantee of the National Science Foundation's Antarctic Artist and Writers Program allow viewers to experience these geological forms in three-dimensional space, not limited by the fixed perspective of a photograph. I spent a total of seven weeks at the end of 2015 at the U.S. Antarctic Program's McMurdo Station and at scientific field camps. I have developed an innovative method of producing sculpture true to the complexity of the natural world by employing photogrammetry, a process by which a series of still photos of a scene (or "captures") can be assembled by software into a three-dimensional scan of a scene. The scans become the basis for sculptures made with digital fabrication technologies such as 3D printing or CNC (computer-controlled) routers, a machine that can carve a 3D file in a variety of materials. On the router I typically use high-density urethane foam for its ability to hold detail yet be easily carved later with hand tools. The scan produced by the photogrammetric software is by no means ready for production. A variety of artistic decisions must be made, and small areas of the form that the software could not resolve have to be filled in using 3D modeling software, a painstaking process because the files are extremely complex — each scan consists of some 2 million tiny triangular facets. Once the piece has been carved or printed in sections and glued together, I refine the piece by hand and paint it. If I had the funding, I could produce them in higher-quality materials such as cast stone or metal.

-

Canada Glacier from Lake Fryxell, AntarcticaCanada Glacier from Lake Fryxell, Antarctica (2015), archival pigment print, 32.5 x 50 inches. Section of the Canada Glacier captured in the 3D file. A section of the massive, spired 60-foot-high side of the Canada Glacier photographed from the frozen surface of Lake Fryxell. The journey here entailed crossing the melted margin in a rowboat used by lake scientists and a bumpy ride over the ice on an ATV.

Canada Glacier from Lake Fryxell, AntarcticaCanada Glacier from Lake Fryxell, Antarctica (2015), archival pigment print, 32.5 x 50 inches. Section of the Canada Glacier captured in the 3D file. A section of the massive, spired 60-foot-high side of the Canada Glacier photographed from the frozen surface of Lake Fryxell. The journey here entailed crossing the melted margin in a rowboat used by lake scientists and a bumpy ride over the ice on an ATV. -

Canada Glacier from Lake Fryxell, AntarcticaCanada Glacier from Lake Fryxell, Antarctica (2015), archival pigment print, 32.5 x 50 inches. Section of the Canada Glacier captured in the 3D file. A section of the massive, spired 60-foot-high side of the Canada Glacier photographed from the frozen surface of Lake Fryxell. The journey here entailed crossing the melted margin in a rowboat used by lake scientists and a bumpy ride over the ice on an ATV.

Canada Glacier from Lake Fryxell, AntarcticaCanada Glacier from Lake Fryxell, Antarctica (2015), archival pigment print, 32.5 x 50 inches. Section of the Canada Glacier captured in the 3D file. A section of the massive, spired 60-foot-high side of the Canada Glacier photographed from the frozen surface of Lake Fryxell. The journey here entailed crossing the melted margin in a rowboat used by lake scientists and a bumpy ride over the ice on an ATV. -

2024-0504-8.jpg

2024-0504-8.jpgInstallation of the Canada Glacier from Lake Fryxell sculpture on view at the Juliet Art Museum, Clay Center, Charleston, West Virginia, in 2024 as part of Walking in Antarctica.

-

CanadaGlacier-2015-12-19_Panorama.jpg

CanadaGlacier-2015-12-19_Panorama.jpgPanorama of Canada Glacier from Lake Fryxell, Antarctica (2015) photograph, 16.5 x 73 inches. The panorama gives some perspective on the size of the glacier. The area I photographed to make the 3D scan for the sculpture is on the left, centered in the area adjoining the lake.

-

Canada Glacier from Lake Hoare, AntarcticaCanada Glacier from Lake Hoare, Antarctica (2017) acrylic on 3D-printed PLA plastic, 11 x 54 x 15.5 inches. Sculpture of the west-facing side of the Canada Glacier. The basic 3D scan was generated via photogrammetry from still photographs and further edited. I printed it in sections, epoxied them together and painted it in acrylics.

Canada Glacier from Lake Hoare, AntarcticaCanada Glacier from Lake Hoare, Antarctica (2017) acrylic on 3D-printed PLA plastic, 11 x 54 x 15.5 inches. Sculpture of the west-facing side of the Canada Glacier. The basic 3D scan was generated via photogrammetry from still photographs and further edited. I printed it in sections, epoxied them together and painted it in acrylics. -

Canada Glacier from Lake Hoare, AntarcticaCanada Glacier from Lake Hoare, Antarctica (2015) archival pigment print, 26.5 x 40 inches. The west facing side of the Canada Glacier rests alongside the Lake Hoare field camp. A row of sandbags has been placed at the edge of the area where meltwater flows in a stream during the austral summer.

Canada Glacier from Lake Hoare, AntarcticaCanada Glacier from Lake Hoare, Antarctica (2015) archival pigment print, 26.5 x 40 inches. The west facing side of the Canada Glacier rests alongside the Lake Hoare field camp. A row of sandbags has been placed at the edge of the area where meltwater flows in a stream during the austral summer. -

2024-0201 Fairfield-2-3.jpg

2024-0201 Fairfield-2-3.jpgGiant's Face" Pressure Ridge, McMurdo Sound, Antarctica (2017) acrylic, oil and wax on 3D-printed PLA plastic and polymer-modified gypsum, 19.5 x 36 x 15.5 inches, with one of the source photographs above it, 22 x 15.675 inches. Sculpture of a 20-foot-high Baroque looking sea ice pressure ridge in a remote section of New Harbor. The basic 3D scan was generated via photogrammetry, further edited, printed in sections and epoxied together. I added the icicles by hand and then painted it. This photo is from the installation of Walking in Antarctica at the Fairfield University Art Museum in 2024.

-

2024-0304 Fairfield-5-2.jpg

2024-0304 Fairfield-5-2.jpgThis alcove of the Fairfield University Art Museum's 2024 installation of Walking in Antarctica includes photographs and sculptures from the section of the exhibition titled "A Walk Over the Canada Glacier."

Walking in Antarctica: Ventifacts & Blood Falls, Dry Valleys, Antarctica

Walking in Antarctica consists of photographs, sculptures from 3D scans of geological formations, and a first-person audio tour, resulting from a seven-week residency in Antarctica in 2015 through the National Science Foundation Antarctic Artists and Writers Program.

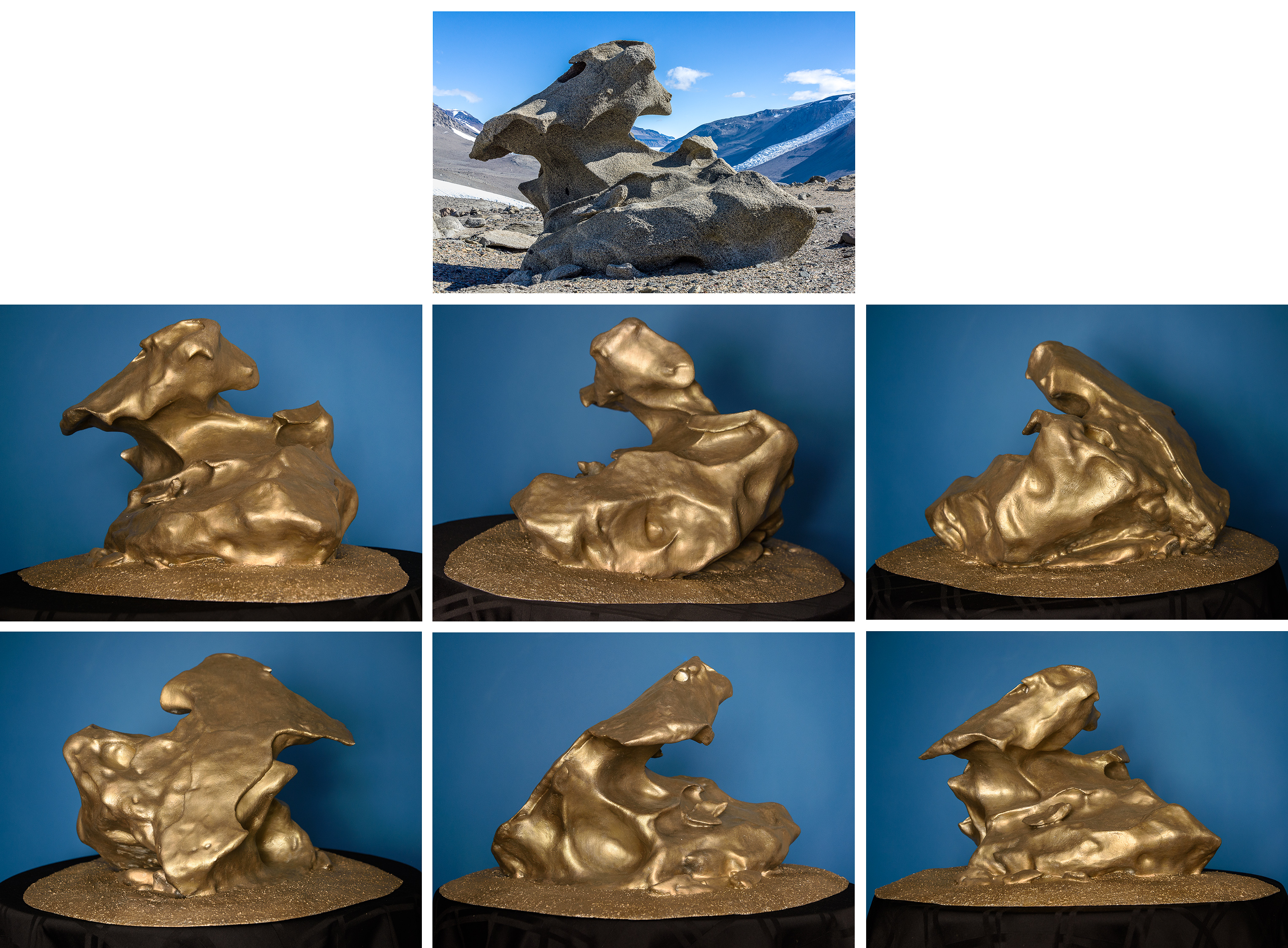

On Dec. 16th, 2015, with a mountaineer guide, I visited Blood Falls, a glacier stained with unique iron formations. The following day, the guide and I hiked up some steep gravel inclines in the McMurdo Dry Valleys above Lake Bonney to elevated ridges and plateaus to see the ventifacts. These are large granite boulders that have been pummeled by fierce winds picking up grains of gravel — imagine a giant sandblaster over millennia. It was a steady climb for well over an hour and then we came over a ridge where the ground was strewn with huge granite boulders curved, hollowed and pierced into strange shapes. I felt like I’d entered the world’s largest Surrealist sculpture garden. I circled the formations shown here with the eventual intention of creating 3D files from still photos via photogrammetry (see the Antarctica in 3D section for general information about the process).

The Dry Valleys are the largest relatively ice-free region in Antarctica, encompassing a cold and windy desert ecosystem with lakes that have a permanently frozen cover of about 4 meters of ice and rare life forms (mostly microorganisms) that have adapted to the extreme conditions — these are active for only two to three months a year and otherwise lie dormant. By international treaty, they are an Antarctic Specially Managed Area. Other than the small number of scientists and science support personnel who do research in the Dry Valleys during the austral summer, very few people have even seen the ventifact fields. Even fewer have been allowed to visit Blood Falls, which is an Antarctic Specially Protected Area and requires an additional permit be issued in advance from a national Antarctic program.

-

"Seated Figure" Ventifact, Dry Valleys, Antarctica"Seated Figure" Ventifact, Dry Valleys, Antarctica (2015), photograph, 14.675 x 22 inches. The ventifacts present very different sculptural profiles as you walk around them. None of the ventifacts have official names. Any names in quotes are ones I gave them for reference. This one reminded me of a seated figure.

"Seated Figure" Ventifact, Dry Valleys, Antarctica"Seated Figure" Ventifact, Dry Valleys, Antarctica (2015), photograph, 14.675 x 22 inches. The ventifacts present very different sculptural profiles as you walk around them. None of the ventifacts have official names. Any names in quotes are ones I gave them for reference. This one reminded me of a seated figure. -

"Seated Figure" Ventifact, Dry Valleys, Antarctica"Seated Figure" Ventifact, Dry Valleys, Antarctica (2015) photograph. The ventifacts present very different sculptural profiles as you walk around them. Compare this to the previous and following photo of the same formation. None of the ventifacts have official names. Any names in quotes are ones I gave them for reference.

"Seated Figure" Ventifact, Dry Valleys, Antarctica"Seated Figure" Ventifact, Dry Valleys, Antarctica (2015) photograph. The ventifacts present very different sculptural profiles as you walk around them. Compare this to the previous and following photo of the same formation. None of the ventifacts have official names. Any names in quotes are ones I gave them for reference. -

Matterhorn Framed by Ventifacts, Dry Valleys, AntarcticaMatterhorn Framed by Ventifacts, Dry Valleys, Antarctica (2015), photograph, 22.375 x 15 inches. This is another view of the "Seated Figure" ventifact shown in two other photographs. It frames a view of a mountain peak on the opposite side of the valley called The Matterhorn.

Matterhorn Framed by Ventifacts, Dry Valleys, AntarcticaMatterhorn Framed by Ventifacts, Dry Valleys, Antarctica (2015), photograph, 22.375 x 15 inches. This is another view of the "Seated Figure" ventifact shown in two other photographs. It frames a view of a mountain peak on the opposite side of the valley called The Matterhorn. -

"Tanguy" Ventifact, Dry Valleys, Antarctica"Tanguy" Ventifact, Dry Valleys, Antarctica (2015), photograph,13.75 x 22 inches. None of the ventifacts have official names. Any names in quotes are ones I gave them for reference. This one reminds me of Surrealist landscape paintings by Yves Tanguy from the mid 20th century. It is also a source photo intended for eventual processing as a 3D file and sculpture.

"Tanguy" Ventifact, Dry Valleys, Antarctica"Tanguy" Ventifact, Dry Valleys, Antarctica (2015), photograph,13.75 x 22 inches. None of the ventifacts have official names. Any names in quotes are ones I gave them for reference. This one reminds me of Surrealist landscape paintings by Yves Tanguy from the mid 20th century. It is also a source photo intended for eventual processing as a 3D file and sculpture. -

06 Glazer Bird Ventifact.jpg"Bird" Ventifact, Dry Valleys, Antarctica (2015) photograph, 14.75 x 22 inches. Source photo for the 3D scan from which I made the sculpture shown in other images of this project. None has an official name, but it reminded me of a bird.

06 Glazer Bird Ventifact.jpg"Bird" Ventifact, Dry Valleys, Antarctica (2015) photograph, 14.75 x 22 inches. Source photo for the 3D scan from which I made the sculpture shown in other images of this project. None has an official name, but it reminded me of a bird. -

"Bird" Ventifact, Dry Valleys, Antarctica"Bird" Ventifact, Dry Valleys, Antarctica (2016), acrylic on 3D-printed PLA plastic and polymer-modified gypsum, 16 x 29.5 x 29.5 inches. At the top of the steep, gravel-covered hill above Lake Bonney in the McMurdo Dry Valleys is a plateau strewn with ventifacts, giant boulders eroded into strange shapes by fierce winds. I called it the Surrealist sculpture garden. I made a 3D scan of this six-foot-tall boulder and printed it in sections on a 3D printer. A video of the process is shown on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qdY3xDGPDf0

"Bird" Ventifact, Dry Valleys, Antarctica"Bird" Ventifact, Dry Valleys, Antarctica (2016), acrylic on 3D-printed PLA plastic and polymer-modified gypsum, 16 x 29.5 x 29.5 inches. At the top of the steep, gravel-covered hill above Lake Bonney in the McMurdo Dry Valleys is a plateau strewn with ventifacts, giant boulders eroded into strange shapes by fierce winds. I called it the Surrealist sculpture garden. I made a 3D scan of this six-foot-tall boulder and printed it in sections on a 3D printer. A video of the process is shown on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qdY3xDGPDf0 -

"Bird" Ventifact, Dry Valleys, Antarctica"Bird" Ventifact, Dry Valleys, Antarctica (2016), acrylic on 3D-printed PLA plastic and polymer-modified gypsum, 16 x 29.5 x 29.5 inches. At the top of the steep, gravel-covered hill above Lake Bonney in the McMurdo Dry Valleys is a plateau strewn with ventifacts, giant boulders eroded into strange shapes by fierce winds. I called it the Surrealist sculpture garden. I made a 3D scan of this six-foot-tall boulder and printed it in sections on a 3D printer. A video of the process is shown on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qdY3xDGPDf0