Work samples

-

Eye For An Eye I

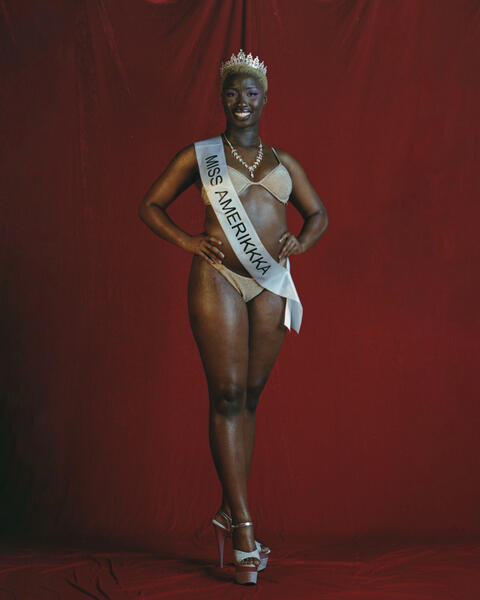

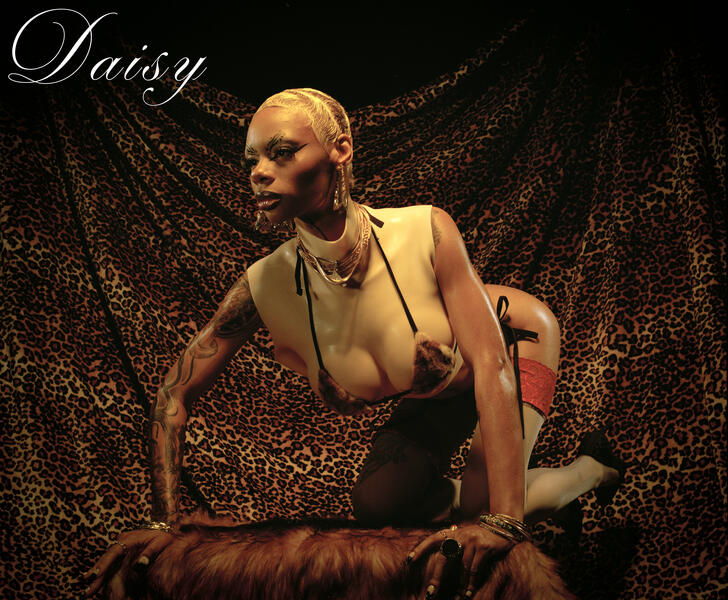

Eye For An Eye IColonial Spirits addresses the hyper-sexualization of Black womanhood and misogyny through the lens of pageantry as a vessel for exploration. During the 1800s, during slavery, "human zoos" were common. These zoos were public displays of people in their "natural" or "primitive" states, meant ot emphasize the supposed inferiority of the exhibited people and present them as "savage." One of the most prominent individuals documented in these exhibitions was Sarah Baartman (Hottentot Venus), an enslaved woman known for her curvaceous body (top left). Due to her genetic differences from European spectators, she was subjected to exploitation. She was caged, poked, prodded at, and made a spectacle. More recently, we see these body standards praised in multiple communities, with the rise of plastic surgery and mentions of Baartman's body type in music.

Reflecting on this history led me to explore pageantry as a modern "human zoo". While women in pageants are not subjected to chains or cages. Parallels can be drawn from the impacts of misogyny, racism, and imposed Eurocentric beauty standards, as black women did not hold space in these contests until the late 20th century. I aim to navigate these ideals through my work using pageantry as an overarching theme. Drawing inspiration from drag culture, costuming, and artists Deana Lawson, Nadia Lee Cohen, Renee Cox, Lorna Simpson, Carrie Mae Weems, Kara Walker, Nikki S. Lee, and more, I channeled this breadth of knowledge and research into creating a character for thematic exploration.

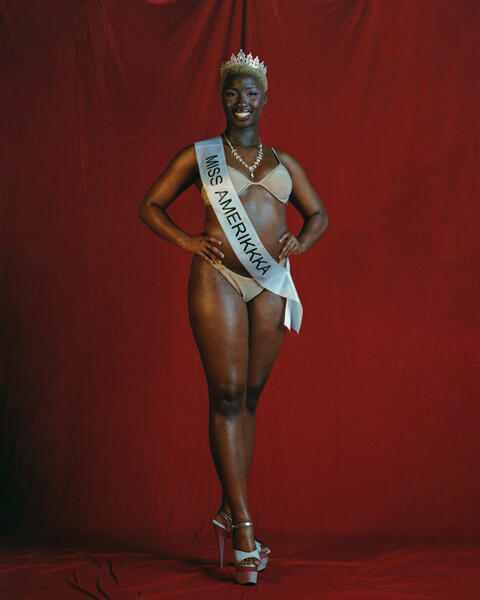

The character I have embodied, Ms. Amerikkka, is a pseudonym to explore the Black American position. Ms. Amerikkka is a Black woman dressed in an American flag bikini with a pale, white D-cup breastplate. She has voluminous, Dolly Parton-esque blonde hair and wears bold blue eyeshadow, red lipstick, thin blonde eyebrows, a sash, and a tiara. Through the projects Pennsylvania Avenue, Since Why is Difficult to Handle, One Must Seek Refuge in How, Amerikkkan Girls, and Eye For an Eye, she symbolizes the appropriation of the Black body/space and seeks repossession. She highlights the white gaze and its impact on the perception of Black Women in both media and everyday life.

Ms. Amerikkka seeks reclamation over the Black body and space. She not only mocks Eurocentric beauty standards but invites us into spaces where black bodies have been exploited, mistreated, ostracized, and alienated. -

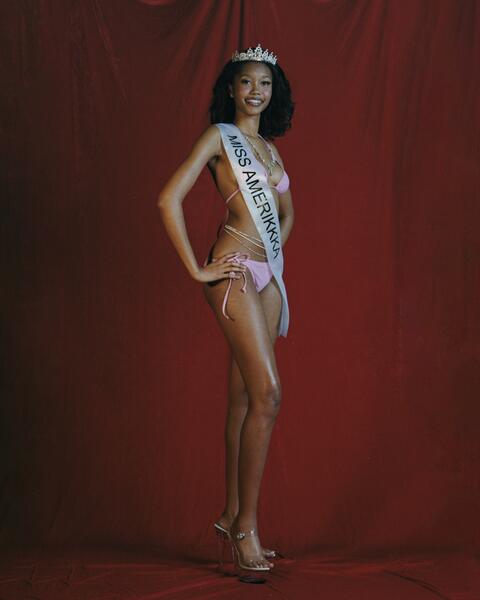

Amerikkkan Girls: Letitia

Amerikkkan Girls: LetitiaIn the midst of making a critique of systemic injustices and prejudices towards black women, the Amerikkkan Girls series allows space for Black women to just exist. This space does not confine what we should be, how we should act, or look. Though these women are styled as pageant girls, all of them are Miss Amerikkka. They allow space to see yourself in each person while mocking the eurocentric gaze of how a Black woman “should” be perceived.

-

Pennsylvania Avenue Beach

Pennsylvania Avenue BeachThe Pennsylvania Avenue series explores the black body in relationship to space. I am investigating “black spaces” through neighborhoods, communal gatherings, and practices to counteract a form of bodily gentrification. Bodily gentrification is like that of assimilation; it is the reduction of habit in hopes to make space for whiteness. My work counteracts this notion through conceptual and visual juxtaposition.

Pennsylvania Avenue Beach (2024) evaluated the ideas of the American Dream. Stereotypically, the American dream has been reserved for certain groups and excluded many others. The idea of rest and vacation is an aspect of this dream that has been systematically reserved. This project seeks to reclaim this notion and project a black body within a predominantly Black neighborhood in a space of relaxation.

Pennsylvania Avenue Cookout (2025). Is forged from the same interest in reevaluating the American Dream. This project looks at the White House (the people’s house) as a space that, though built by African Americans, has failed through action, legislation, and inclusion to represent a significant demographic of this nation’s population. I seek to answer what reclamation of this space could look like physically. The urgency of community and rest, especially within tumultuous times, is a necessity. Through staging a cookout on the white house lawn, I invite my community into a space we have built and reclaim it. By contrasting full-bleed images and studio images, I speak to this push and pull of tangibility, inclusion, the lack thereof, and attainability.

-

Since Why is Difficult To Handle, One Must Seek Refuge in How

Since Why is Difficult To Handle, One Must Seek Refuge in HowWhen approaching a subject that is often dismissed, how do we say: “I have been harmed. My sisters, our mothers, and their mothers have been harmed. But our bodies are not a receptacle of this lashing, so I persist in this body—unabashedly.”

I recount experiences in school when other Black girls and I had our attire “dress-coded,” as our clothes were deemed “inappropriate”—outfits for which white girls often did not face the same repercussions. A 2018 study by the National Women's Law Center found that Black girls in Washington, D.C. were more likely to be targeted for dress code violations than white girls, and 20.8 times more likely to be suspended from school.

From zoo entrapments, gynecological research, and Jezebel stereotypes, to school dress codes, there has always been an attack on the Black female/woman’s body. We live in a world that criticizes and questions its little Black girls for how they dress, labels them for how they present, and asks what was worn during traumatic events. I can recount being asked by adults, “Did your mother know you left the house in that?” as I wore leggings, shorts, or a top that exposed my midriff. More recently, in my encounters with men, it has become commonplace for my body to be reduced to what I could give in service to them. These experiences have had an impact on how I view myself—battling with the notion that I am disposable unless in service to another body, or shameful if I am autonomous of my own. This sparked my interest in depicting what it means to shift perceptions/stereotypes.

I named this project "Since Why is Difficult to Handle, One Must Take Refuge in How" after reading Toni Morrison’s “The Bluest Eye.” The book is a riveting exploration of the internalized effects of racism and its external harm, particularly to Black girls. Morrison confronts the pain of systemic oppression, revealing the painful “why.” In the book’s forward, Morrison writes, “There is really nothing more to say—except why. But since it is difficult to handle, one must take refuge in how." This quote resonated with my own experiences with hyper sexualization and navigating reclamation in the face of harm. Growing up hearing the things I heard and seeing what I saw, I could not help but wonder, why? Why was I and so many like me treated this way? Now, I seek to remove the why, as it was never me or us to be faulted. Rather, I would like to question: what, who, and how?

Through the use of original, familial archival imagery (in exhibition), a poster girl-esc style of photographic composition, and dress, I create easily identifiable access points and juxtaposition. Since Why Is Difficult to Handle, One Must Take Refuge in How begs the viewer to assess their relationship with preconceived notions of Black female 'promiscuity' and asks Black women: How do we own, love, and persist in our bodies despite the harm done?

About Alaina

Alaina Lurry (she/her) is an Atlanta-born, Baltimore-based image maker and creative director. Her work explores the intricacies of Black womanhood and self-identity. She creates spaces of comfort for her community while honoring Blackness with care and authenticity, all while critiquing societal perceptions of Blackness. Through research, set design, costuming, and image-making, Alaina stylistically investigates the intersections of Black womanhood through comparison, juxtaposition, and… more

Colonial Spirits: Eye For An Eye

Colonial Spirits addresses the hyper-sexualization of Black womanhood and misogyny through the lens of pageantry as a vessel for exploration. During the 1800s, during slavery, "human zoos" were common. These zoos were public displays of people in their "natural" or "primitive" states, meant ot emphasize the supposed inferiority of the exhibited people and present them as "savage." One of the most prominent individuals documented in these exhibitions was Sarah Baartman (Hottentot Venus), an enslaved woman known for her curvaceous body (top left). Due to her genetic differences from European spectators, she was subjected to exploitation. She was caged, poked, prodded at, and made a spectacle. More recently, we see these body standards praised in multiple communities, with the rise of plastic surgery and mentions of Baartman's body type in music.

Reflecting on this history led me to explore pageantry as a modern "human zoo". While women in pageants are not subjected to chains or cages. Parallels can be drawn from the impacts of misogyny, racism, and imposed Eurocentric beauty standards, as black women did not hold space in these contests until the late 20th century. I aim to navigate these ideals through my work using pageantry as an overarching theme. Drawing inspiration from drag culture, costuming, and artists Deana Lawson, Nadia Lee Cohen, Renee Cox, Lorna Simpson, Carrie Mae Weems, Kara Walker, Nikki S. Lee, and more, I channeled this breadth of knowledge and research into creating a character for thematic exploration.

The character I have embodied, Ms. Amerikkka, is a pseudonym to explore the Black American position. Ms. Amerikkka is a Black woman dressed in an American flag bikini with a pale, white D-cup breastplate. She has voluminous, Dolly Parton-esque blonde hair and wears bold blue eyeshadow, red lipstick, thin blonde eyebrows, a sash, and a tiara. Through the projects Pennsylvania Avenue, Since Why is Difficult to Handle, One Must Seek Refuge in How, Amerikkkan Girls, and Eye For an Eye, she symbolizes the appropriation of the Black body/space and seeks repossession. She highlights the white gaze and its impact on the perception of Black Women in both media and everyday life.

Ms. Amerikkka seeks reclamation over the Black body and space. She not only mocks Eurocentric beauty standards but invites us into spaces where black bodies have been exploited, mistreated, ostracized, and alienated.

Amerikkkan Girls

In the midst of making a critique of systemic injustices and prejudices towards black women, the Amerikkkan Girls series allows space for Black women to just exist. This space does not confine what we should be, how we should act, or look. Though these women are styled as pageant girls, all of them are Miss Amerikkka. They allow space to see yourself in each person while mocking the eurocentric gaze of how a Black woman “should” be perceived.

Pennsylvania Aveune

Pennsylvania Avenue explores the Black body in relationship to space. I am investigating “Black spaces” through neighborhoods, communal gatherings, and practices to counteract a form of bodily gentrification. Bodily gentrification is like that of assimilation; it is the reduction of habit in hopes to make space for whiteness. My work counteracts this notion through conceptual and visual juxtaposition.

Pennsylvania Avenue Beach (2024) evaluated the ideas of the American dream. Stereotypically, the American dream has been reserved for certain groups and excluded many others. The idea of rest and vacation is an aspect of this dream that has been systematically reserved. This project seeks to reclaim this notion and forge a space for relaxation within the historic, predominantly Black neighborhood of Pennsylvania Avenue in Baltimore, Maryland.

Pennsylvania Avenue Cookout (2025). Is forged from the same interest in reevaluating the American Dream. This project looks at the White House (the people’s house) as a space that, though built by African Americans, has failed us through action, legislation, and inclusion. I seek to answer what reclamation of this space could look like physically. The urgency of community and rest, especially within tumultuous times, is a necessity. Through staging a cookout on the White House lawn, I invite my community into a space we have built and reclaim it. By contrasting full-bleed images and studio images, I speak to this push and pull of tangibility, inclusion, the lack thereof, and attainability.

Since Why Is So Difficult to Handle, One Must Take Refuge In How.

When approaching a subject that is often dismissed, how do we say: “I have been harmed. My sisters, our mothers, and their mothers have been harmed. But our bodies are not a receptacle of this lashing, so I persist in this body—unabashedly.”

I recount experiences in school when other Black girls and I had our attire “dress-coded,” as our clothes were deemed “inappropriate”—outfits for which white girls often did not face the same repercussions. A 2018 study by the National Women's Law Center found that Black girls in Washington, D.C. were more likely to be targeted for dress code violations than white girls, and 20.8 times more likely to be suspended from school.

From zoo entrapments, gynecological research, and Jezebel stereotypes, to school dress codes, there has always been an attack on the Black female/woman’s body. We live in a world that criticizes and questions its little Black girls for how they dress, labels them for how they present, and asks what was worn during traumatic events. I can recount being asked by adults, “Did your mother know you left the house in that?” as I wore leggings, shorts, or a top that exposed my midriff. More recently, in my encounters with men, it has become commonplace for my body to be reduced to what I could give in service to them. These experiences have had an impact on how I view myself—battling with the notion that I am disposable unless in service to another body, or shameful if I am autonomous of my own. This sparked my interest in depicting what it means to shift perceptions/stereotypes.

I named this project "Since Why is Difficult to Handle, One Must Take Refuge in How" after reading Toni Morrison’s “The Bluest Eye.” The book is a riveting exploration of the internalized effects of racism and its external harm, particularly to Black girls. Morrison confronts the pain of systemic oppression, revealing the painful “why.” In the book’s forward, Morrison writes, “There is really nothing more to say—except why. But since it is difficult to handle, one must take refuge in how." This quote resonated with my own experiences with hyper sexualization and navigating reclamation in the face of harm. Growing up hearing the things I heard and seeing what I saw, I could not help but wonder, why? Why was I and so many like me treated this way? Now, I seek to remove the why, as it was never me or us to be faulted. Rather, I would like to question: what, who, and how?

Through the use of original, familial archival imagery (in exhibition), a poster girl-esc style of photographic composition, and dress, I create easily identifiable access points and juxtaposition. Since Why Is Difficult to Handle, One Must Take Refuge in How begs the viewer to assess their relationship with preconceived notions of Black female 'promiscuity' and asks Black women: How do we own, love, and persist in our bodies despite the harm done?