Work samples

-

Chapter from The Requirement of Grief titled Voices

Chapter from The Requirement of Grief titled VoicesVoices

After the “break-in,” Alexis stays with our parents while she recovers. Weeks slide by and soon it has been a month. She’s terrified to return to her apartment, but living with my parents is not sustainable. The more time that passes, the more the three of them clash and argue. When she finally goes back to her place, my parents breathe a sigh of relief, but it’s not long before she begins calling home to complain about her neighbors.

“They yell at me through the walls,” she tells my mom. “They say my T.V. is too loud.”

When my mother relays these stories to me, I wonder who the hell these people think they are. I find myself googling the address of the neighbors, which leads me to a property record with the name of the person who owns the rowhouse next to hers. I type the neighbor’s name into the search engine and wind up staring at a picture of a lovely blonde-haired woman on the website of a Philadelphia law firm where she is an attorney. I look at the photo, feeling disappointed, realizing that I was hoping to find some proof that this woman was bad news—a mug shot would’ve been the jackpot, but I would have settled for something smaller, like a quote in a news story that showed she was mean-spirited. But there’s just this lawyer picture of her, looking all put together.

I share the results of my online sleuthing with my parents and we try our best to make sense of it. Every time I talk to my mom or dad, this topic dominates our conversations. We volley questions back and forth and put together all sorts of extremely unlikely scenarios that could explain the things my sister keeps describing.

Why would anyone do this?

Do you think it’s because she’s up all night?

Maybe she makes a lot of noise? Plays her T.V. too loud?

Maybe she has people over to her place and they’re up partying?

Do you think she should call her landlord?

“There are some sick people in the world,” my mom says. “I mean, really sick. Who knows what’s going on!”

Over the next couple of weeks, Alexis continues to call my parents with more and more stories about harassment. All the stories have a similar frame, with the people yelling through the walls for no reason, but then one day the story changes.

“Your sister said there was a man on the roof messing with her cable dish and that he was talking to her through the T.V. Could that happen?” my mom asks me. “Could a technician do that?”

“No Mom,” I say softly, realizing that the things Alexis has been describing are not real. I’ve had countless moments like this before, where the truth has come into sharp focus, only to blur again. This moment is significant not because it’s the first time I’ve had this realization, but because it’s the last time I’ll need to have it. The time that the haze of denial fully lifts. I feel the familiar tug of both shock and recognition. “Of course” wrapped deeply inside of “I can’t believe this.”

But my mother can’t fathom that some of Alexis’s claims don’t have a basis in reality, so she makes plans to spend the night at my sister’s apartment.

“I want to hear these friggin’ people for myself,” she tells me the next time we talk.

“What? Where are you going to sleep?”

“On the couch.”

“That tiny thing?”

“It’s only one night.”

I think of my mother with her bad back curled up on the loveseat, listening for things that she’ll never hear.

“And what if you don’t hear anyone? Then what? Are you going to stay a second night?”

“Well…we’ll see.”

But before the sleepover happens Alexis calls my mother at work, screaming that she’s been robbed. She’s hysterical, says her wallet is missing. My mother calls my father. They both leave work and drive down to Alexis’s apartment. When they get there, Alexis is limping around, her feet covered with blisters from a pair of shoes that she wore out to a bar the night before. Her T.V. has been knocked off the stand near the kitchen window.

“I was dusting the window for prints and it fell,” she tells them when they ask why it’s on the floor.

They find the wallet beneath one of the many piles on the floor of her messy apartment. But Alexis insists that someone had been there and robbed her. She points to a brown smear on the floor.

“See that?” she says. “They tracked dog shit in here.”

My father gets down on his hands and knees to look at the mark, to smell it, discovers that it’s a brownie.

“My feet hurt so bad. They’re so sore,” she complains.

“C’mon,” my mother says, coaxing her. “Let’s just go get those feet taken care of. We really should have someone look at them.”

“Just my feet?”

“Yes, just your feet. They look so sore.”

They go back and forth like this before Alexis agrees reluctantly.

Once they get to the hospital, the doctors call for a psych evaluation and determine that she needs treatment. When Alexis realizes that she’s being admitted against her will, she begins shouting. A couple of orderlies take her out of the room screaming.

“Thank God,” I say when my dad calls to tell me what happened. “At least we know she’s safe now.”

“She’s pretty angry with us,” he says. “She’s calling Mom and haranguing her. Saying that if Grandpop knew that we’d put her in a mental hospital against her will, he would roll over in his grave.”

I feel the old burn of anger well up in me when I hear this. How can she be both so sick and so manipulative? How is it that she can be totally out of touch with reality and yet still know exactly what buttons to push in order to make our mother feel like shit? Bringing up Mom’s dead father is a new low.

Alexis gets released a few days later, when her hallucinations subside. In the next months, we find out that her landlord will not renew her lease, so we pack up her belongings and she moves in with my parents. The whole episode is like a deep wound. Every time it starts to heal, we move in some way that opens it up all over again. Alexis refers to it as “the time you had me put away.” Years later, when I think of my mother offering to sleep on the tiny loveseat and my father bending down to inspect a brown spot on the floor, I understand deep in my bones that this is what hope looks like.

-

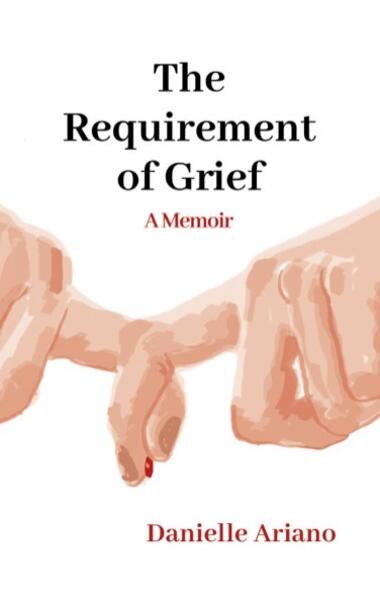

The Requirement of Grief

The Requirement of GriefIn suburban Philadelphia, Danielle Ariano spends much of her childhood attempting to imitate her older sister, Alexis: the way she dresses, speaks, even the way she stands when she smokes. But at the tender age of twelve, Ariano witnesses Alexis’s first suicide attempt, a harrowing event that foreshadows a tumultuous three-decade journey marked by thirteen such acts.

The Requirement of Grief lays bare the relationship between two sisters and the bond that remains in the wake of a suicide. With raw honesty and eloquence, Ariano chronicles her pursuit of healing in the face of loss, traversing the depths of grief day by day, month by month, and year by year, all the way to the birth of her son. As the unparalleled joy of motherhood intertwines with her grief, she grapples with the disorienting experience of having love and sorrow bind together.

In a profoundly moving account that captures the duality of human experience, Ariano puts grief under a microscope, dares to bring it into sharp focus and then watches how it transforms over time.

About Danielle

Danielle Ariano was born and raised in the Philadelphia suburbs, but became a Baltimorean when she moved to the city for college. She was indeed charmed by Baltimore’s quirky, artsy vibe.

Ariano’s memoir, The Requirement of Grief, is a meditation on the complexities of the sister bond and the grief that comes when that bond is broken by a sibling’s suicide.

Ariano received her MFA in Creative Nonfiction from the University of Baltimore. As part of her thesis, she… more

Keeping Time

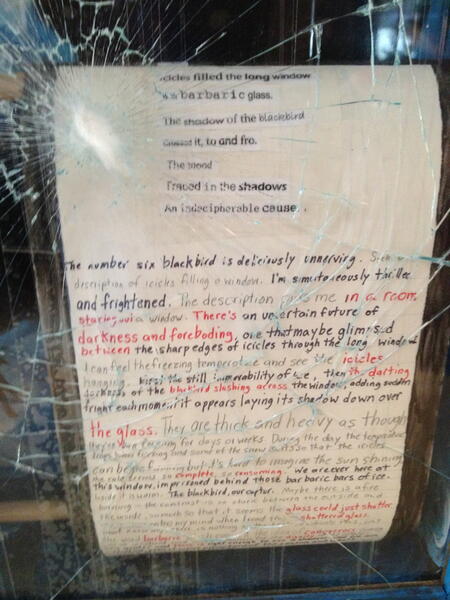

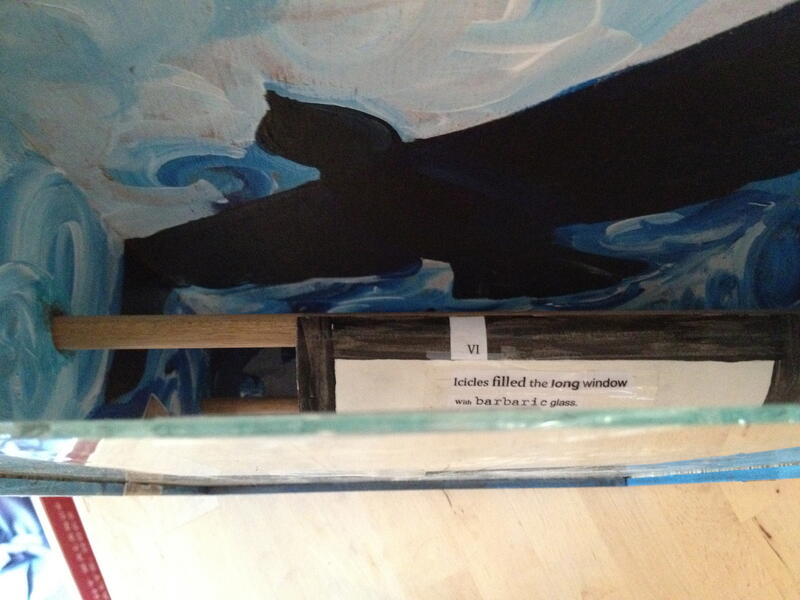

VI

Icicles filled the long window

With barbaric glass.

The shadow of the blackbird

Crossed it, to and fro.

The mood

Traced in the shadow

An indecipherable cause.

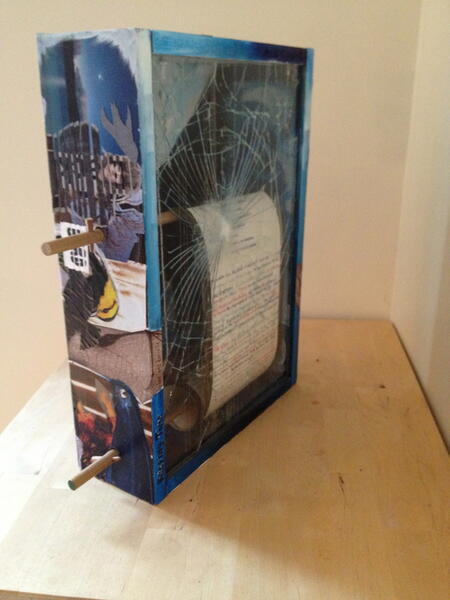

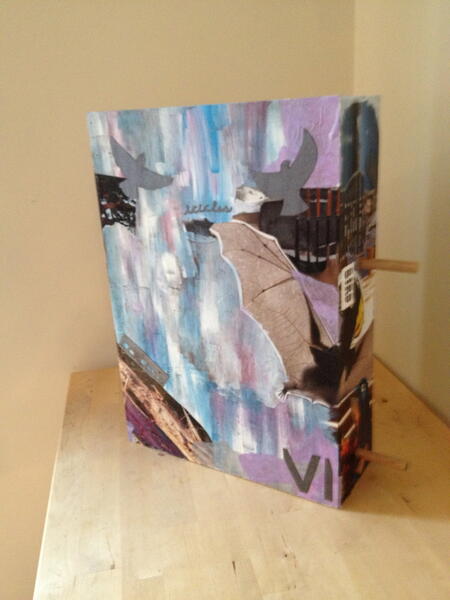

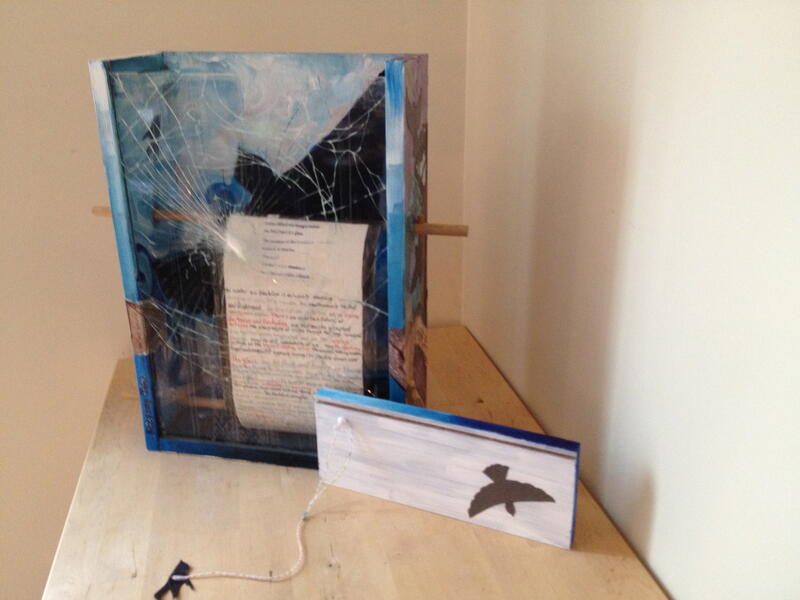

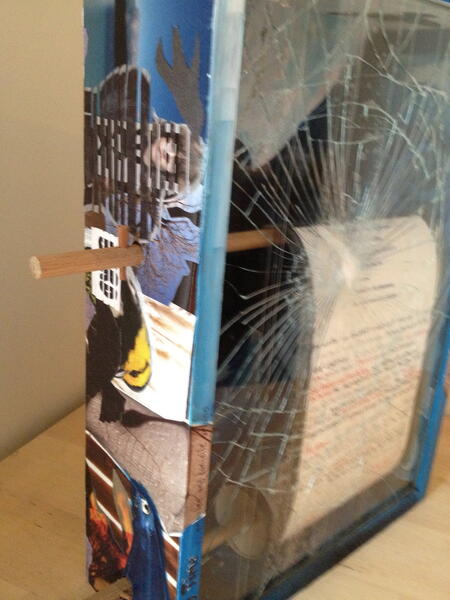

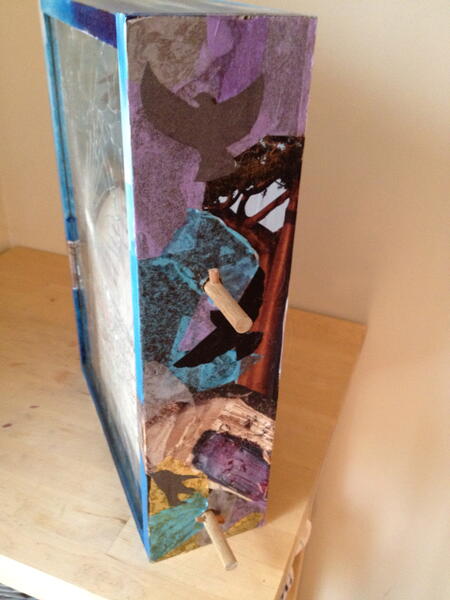

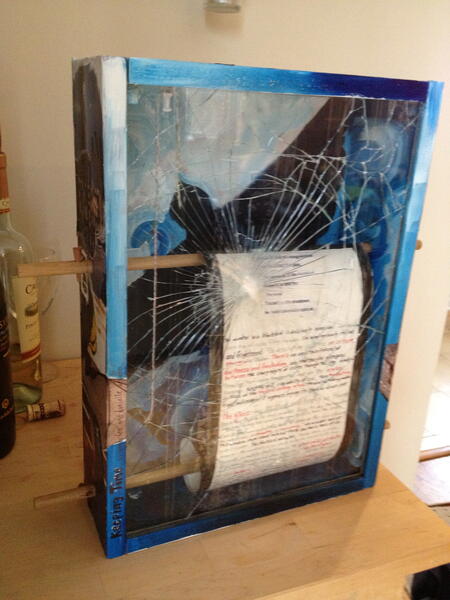

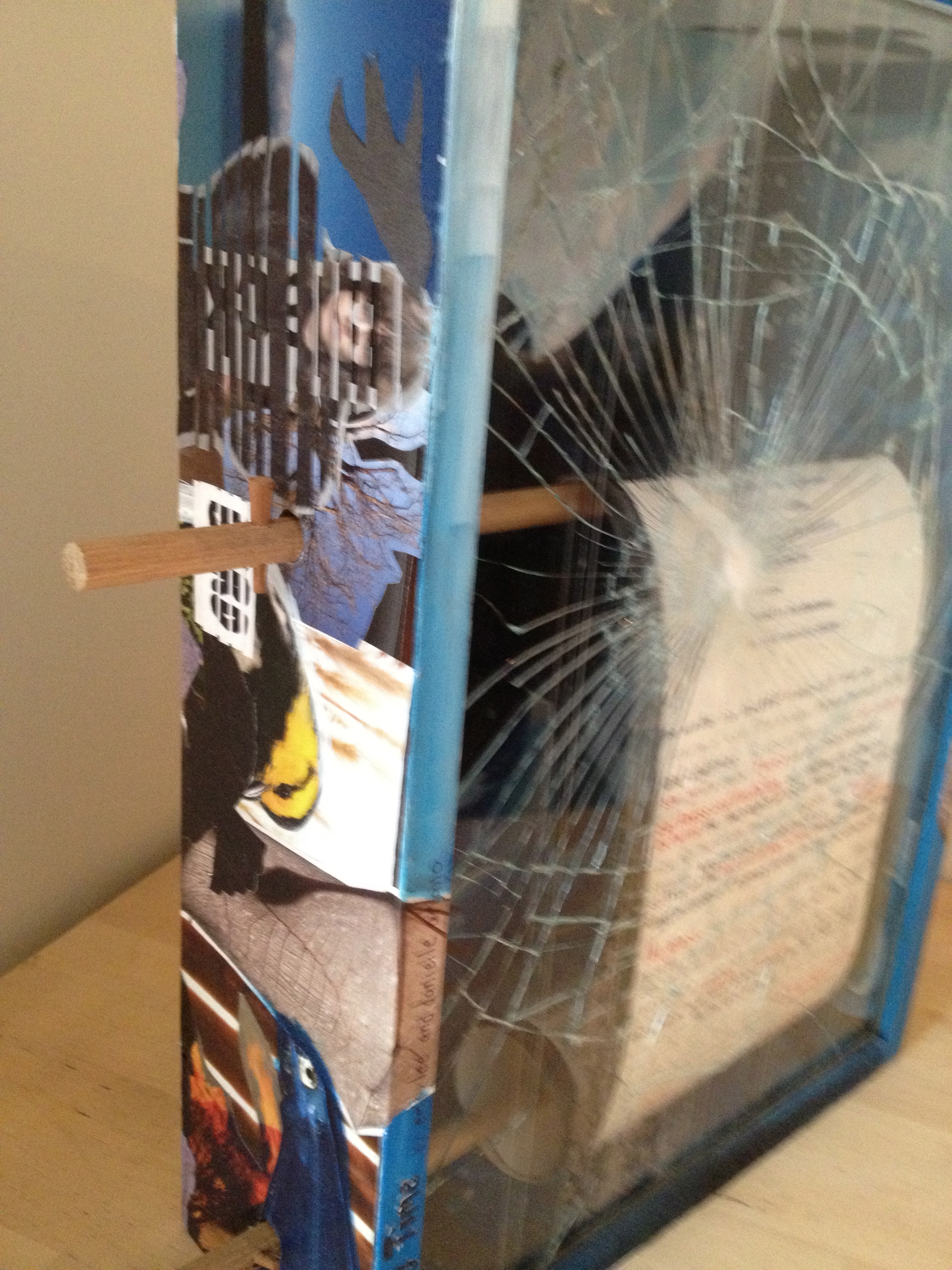

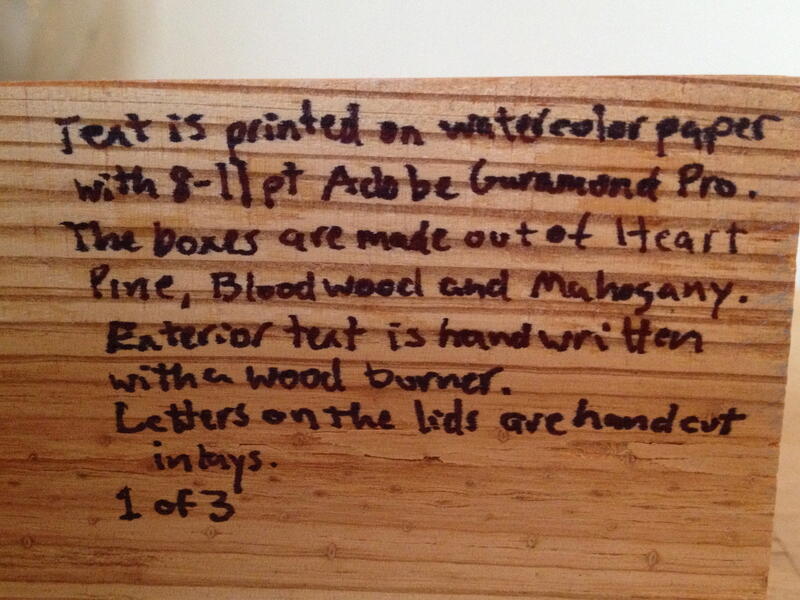

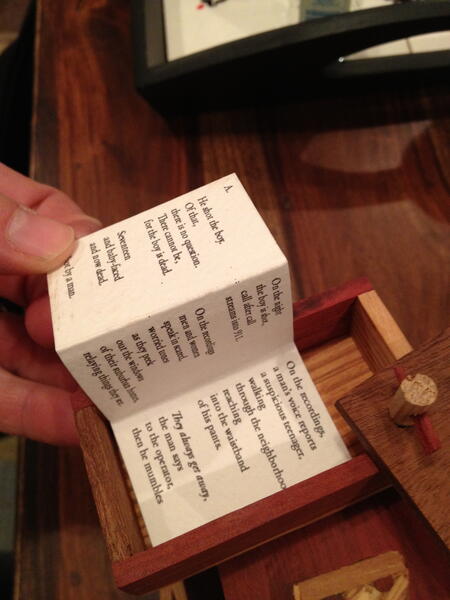

It is a hand built box with a cracked glass window. A scroll containing a collaborative poem can be wound on two dowels that run through the box.

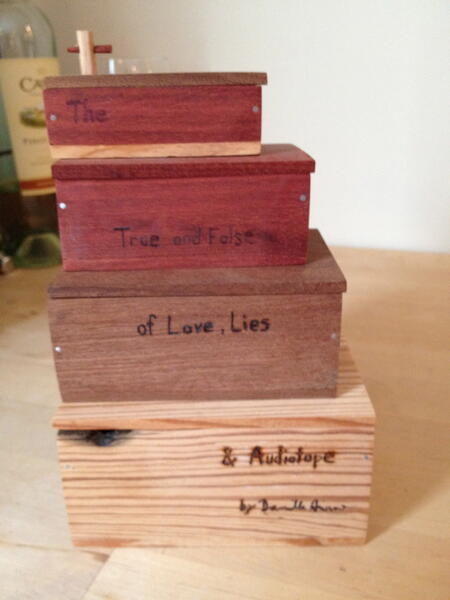

The True and False of Love, Lies & Audiotape

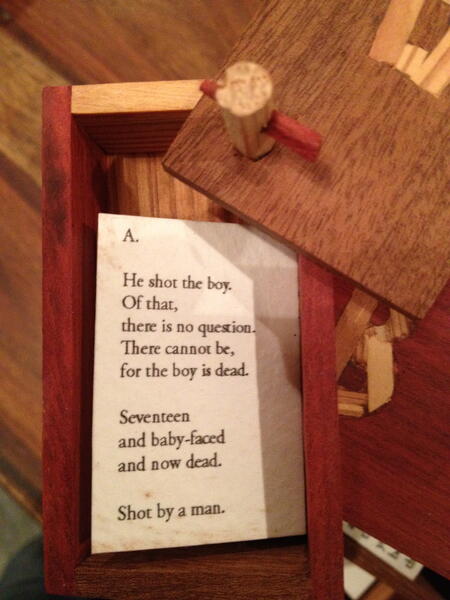

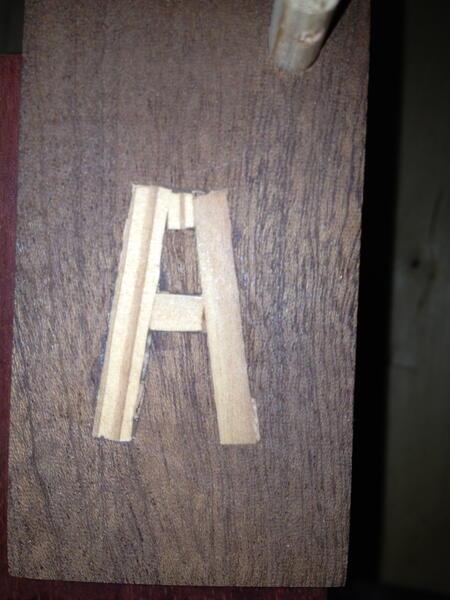

The book is meant to be interactive and to stir questions-both with the text and the form that it is presented.

The poem text is below:

The True and False of Love, Lies & Audiotape

A.

He shot the boy.

Of that,

there is no question.

There cannot be,

for the boy is dead.

Seventeen

and baby-faced

and now dead.

Shot by a man.

On the night the boy is shot,

call after call

streams into 911.

On the recordings

men and women

speak in scared,

worried tones

as they peek

out the windows

of their suburban homes,

relaying things they see.

On the recordings,

a man’s voice reports

a suspicious teenager,

walking

through the neighborhood,

reaching

into the waistband of his pants.

They always get away, the man says to the operator,

then he mumbles a phrase that sets the country on fire:

fuckin coons or fuckin punks,

only the man can say for sure

which one it is,

but all across the nation

people listen to the tape,

the same tape,

and hear different things.

B.

I love you, the one says to the other.

I love you too, the other says to the one,

and with that,

the one goes to bed

and the other

finally stops pretending.

The one has chosen the pretending

over truth

and now it threatens everything.

In the cabinet, the other reaches for a bottle.

Shot after shot slides down into the other

until it all blurs,

until the black and white of truth

bleeds into grey.

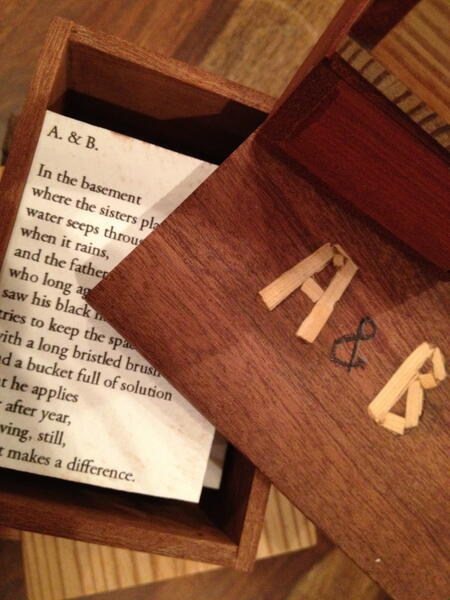

A. & B.

In the basement where the sisters played as children,

water seeps through the walls when it rains,

and the father,

who long ago had his black hair turn grey,

tries to keep the space dry

with a long bristled brush

and a bucket full of solution

that he applies

year after year,

believing, still, that it makes a difference.

A.

On the recordings,

a voice can be heard

screaming for help.

When the boy’s mother

listens to the recordings,

she runs from the room,

certain that the voice

belongs to her son.

B.

Is it in and with or is it just love?

It is an important distinction.

When it is not in and not with,

it does not last because prepositions

create relationships.

A.

Not so, the man says,

the voice is mine,

crying out to the neighbors

after the boy attacked me.

B.

Sometimes when people ask the other what happened,

she wishes she could simply say

I lost the in and with

and that people would understand

that without the in and with,

there wasn’t enough.

But sometimes

she wonders whether she should have stayed,

whether she surrendered too easily to these two

tiny words,

whether in and with are just states of being that

come and go,

rising and falling

like the tides,

like the moon,

cyclical, imminent.

Sometimes she wonders

whether so much should depend upon

the presence

or absence of two words.

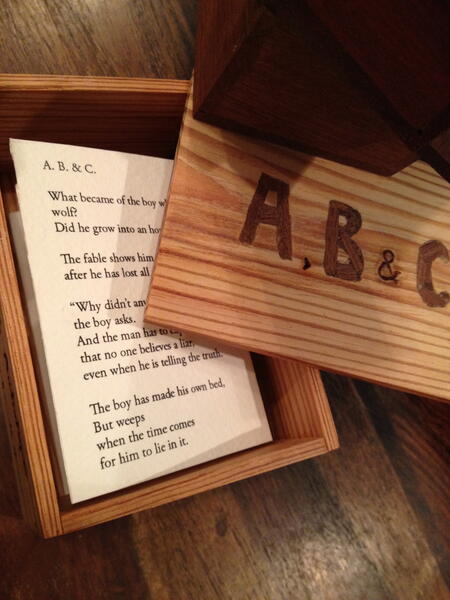

A. B. & C.

What became of the boy who cried wolf?

Did he grow into an honorable man?

The fable shows him crying at the end,

after he has lost all the sheep.

“Why didn’t anyone come?” the boy asks.

And the man has to explain

that no one believes a liar,

even when he is telling the truth.

The boy has made his own bed,

but weeps

when the time comes

for him to lie in it.

A.

At work my colleague asks,

“Wasn’t the guy who shot him Hispanic?”

He asks because he can’t see how race could be an issue

if the guy who shot him was Hispanic,

because if the guy who shot him was Hispanic,

he wasn’t white

and if he wasn’t white, he couldn’t be racist.

B.

When the in and with disappear,

where do they go, she wonders.

She thinks that maybe she could track them down,

wrestle them to the ground,

chisel them in stone,

insert them back into the sentence.

It should be simple.

She works with words,

and when she doesn’t work with words,

she works with her hands

so it should be simple.

They are, after all, just words.