Work samples

-

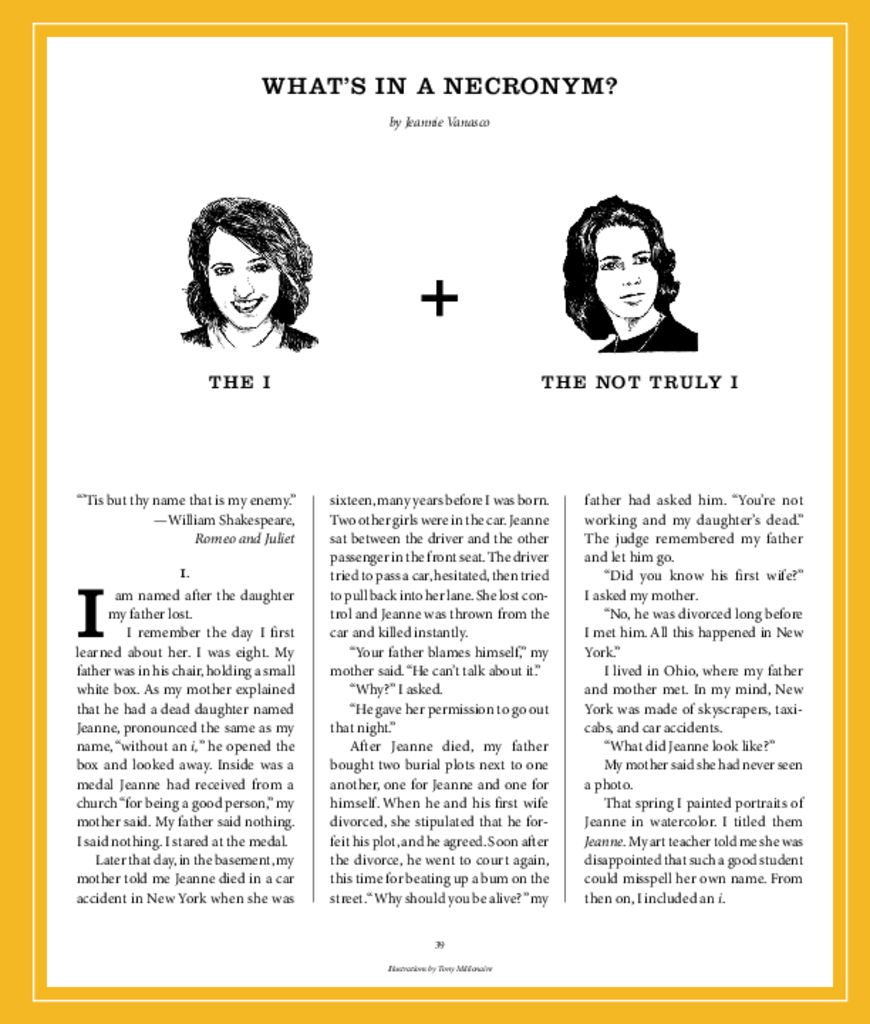

What's in a Necronym?Work Sample: "What's in a Necronym" explores the experience of being named after a dead sibling. The essay also includes stories about artists named after dead siblings. First published in the Believer, "What's in a Necroynm?" was reprinted in Spanish in El Malpensante, reprinted in Italian in Black Coffee, named a Notable Essay in Best American Essays, and featured by Longreads.

-

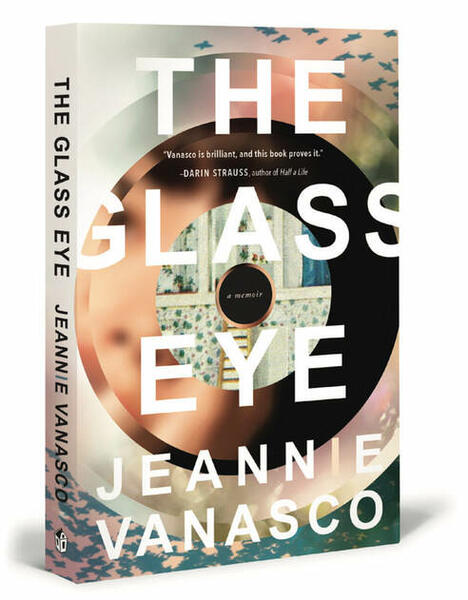

The Glass Eye (excerpt)Work Sample: The Glass Eye (Tin House Books). The night before he died, I promised my dad I would write a book for him. This memoir was my attempt to fulfill that promise. To read the first chapter, please click "View Full Document." For a detailed description of The Glass Eye and to read about my process writing it, please see the projects section of my portfolio.

About Jeannie

Jeannie Vanasco is the author of the memoirs Things We Didn’t Talk About When I Was a Girl (Tin House, 2019)—which was named a New York Times Editors' Choice and a best book of the year by TIME, Esquire, Kirkus, among others—and The Glass Eye (Tin House, 2017), which Poets & Writers called one of the five best literary nonfiction debuts of the year. Her third book, A Silent Treatment (Tin House), will be published… more

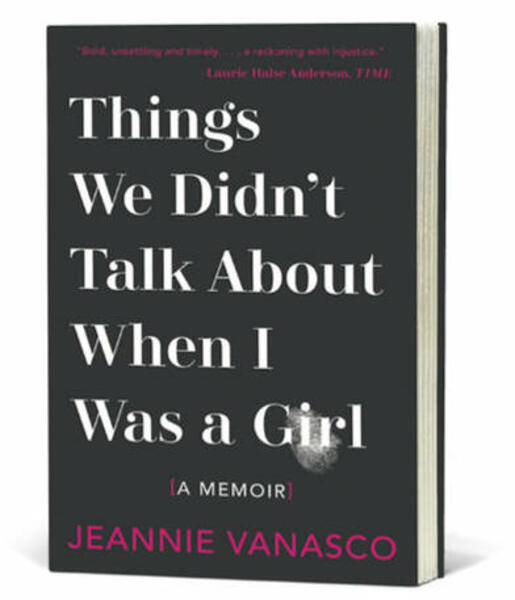

Things We Didn't Talk About When I Was a Girl: A Memoir

Winner of the 2020 Ohio Book Award in Nonfiction

Winner of the 2020 Lawrence J. Epstein Award

Amazon's 20 Best Books of 2019

Kirkus's Best Books of 2019

TIME magazine's Must-Read Books of 2019

Esquire's Best Nonfiction Books of 2019

Book Riot's Favorite Nonfiction of 2019

Electric Lit's 15 Best Nonfiction Books of 2019

Kirkus's Best Books of 2019 to Fight Misogyny and Sexism

Book Riot's 5 of the Best Nonfiction Books About Sexual Assault

Feminist Book Club's Best Books of 2019

Paris Review Staff Pick

Featured at The Paris Review, The Believer, TIME, The Times, The Rumpus Book Club, Ploughshares, NPR, New York's The Cut, and more.

A Fall Pick of 2019 at TIME, Esquire, Publishers Weekly, Bustle, Buzzfeed, Lit Hub, Chicago Tribune, Amazon, Evening Standard, Publishers Marketplace, The Millions, The Rumpus, Vol. 1 Brooklyn, Nylon, Book Riot, Boston Globe, Domino, Waterstones, Pacific Standard, O, the Oprah Magazine, and more.

Published by Tin House Books in the US. Published by Duckworth Books in the UK. Published with Grupa Wydawnicza Relacja in Poland. Published with Frassinelli/Mondadori in Italy.

Things We Didn't Talk About When I Was a Girl (Tin House Books, 2019) is about my former friendship with the man who raped me when we were both nineteen years old. It’s interspersed with interviews with him, conducted in 2018, in an effort to explore how the incident has affected both of our lives.

The rape happened in 2003. Back then, according to the FBI’s definition of rape (the carnal knowledge of a female forcibly and against her will), he hadn’t raped me. As of January 1, 2013, however, according to the FBI, he had raped me. The new definition: Penetration, no matter how slight, of the vagina or anus with any body part or object, or oral penetration by a sex organ of another person, without the consent of the victim. The definition has changed but the action remains the same. Yet, while writing this book, I still felt uncomfortable applying the word "rape."

Because he agreed to recorded interviews for the project, I sometimes questioned the authenticity of his answers and my interpretation of them. Reaching the truth depended on interrogating myself—not just him. The book includes scenes of me discussing it with friends, turning into a meditation on female friendships. Reviewers called my first book, The Glass Eye, “meta” and “experimental” for its acknowledgment of the writing process; however, for my purposes, acknowledging the writing process is more authentic and ethical than it is edgy.

To listen to my conversation with Sheilah Kast of WYPR, please click here or click on the square with the music note icon in this project section.

To listen to my conversation with David Naimon of Between the Covers, please click here or click on the second square with the music note icon in this project section.

To view a PDF file of my conversation in the Believer, please click here or click on the first yellow square in this project section.

To read the first 29 pages of Things We Didn't Talk About When I Was a Girl, please click here or click on the second yellow square in this project section.

To read a short excerpt from one of my interviews with my former friend, please click here or click on the last yellow square in this project section.

To read or listen to additional interviews, please click here.

-

WYPR Interview with Sheilah KastWYPR Interview with Sheilah Kast

-

Interview with David Naimon on Between the CoversThis interview with David Naimon runs for two hours and sixteen minutes. David is one of the best literary interviewers out there. His podcast—which consists of long-form in-depth conversations with writers—has been singled out by the Guardian, Book Riot, the Financial Times, and BuzzFeed as one of the most notable book podcasts for writers and readers around.

-

Conversation in the BelieverFor the Believer magazine, Amy Berkowitz and I conducted a long-form conversation about our books, both of which examine sexual assault.

Excerpt: I don’t know why this surprises me—it shouldn’t—but so many women tell me they know guys exactly like Mark, and so many men point out how terrible Mark is. These men say that Mark resembles no one they know. Really? No one? The way these men think: the bad guys, they’re always over there, drugging and raping women, dangling job “offers” contingent on sex, typing misogynist screeds on 4chan. These nice guys scoff at them. These nice guys say, “I just don’t get it,” as if Cosby, Weinstein, and incels serve as weather vanes for men’s treatment of women. -

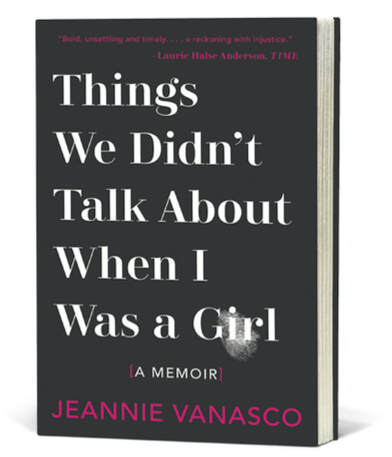

Things We Didn't Talk About When I Was a GirlThis is the paperback cover of Things We Didn't Talk About When I Was a Girl. The memoir was a New York Times Editors' Choice and a TIME magazine Must-Read Book of 2019. It explores my former friendship with the man who raped me. In its starred review, Kirkus called the memoir "an extraordinarily brave work of self- and cultural reflection."

Things We Didn't Talk About When I Was a GirlThis is the paperback cover of Things We Didn't Talk About When I Was a Girl. The memoir was a New York Times Editors' Choice and a TIME magazine Must-Read Book of 2019. It explores my former friendship with the man who raped me. In its starred review, Kirkus called the memoir "an extraordinarily brave work of self- and cultural reflection." -

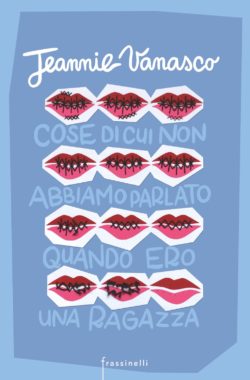

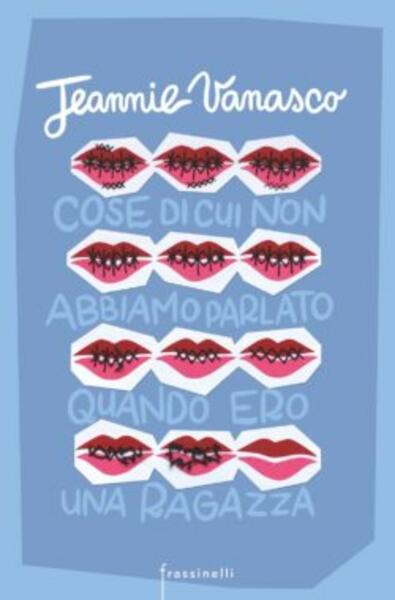

Italian Cover of Things We Didn't Talk About When I Was a GirlThe Italian cover of Things We Didn't Talk About When I Was a Girl is my favorite cover out of the translated versions of this book. The idea of the sewn mouths that slowly free themselves and rediscover the freedom to speak comes from artist/illustrator Camilla Ronzullo, who made the mouths with colored paper, black thread, scissors and needle: "I liked the idea of tightening these mouths with such a symbolic gesture as that of sewing. It was nice for me too, after the fatigue of the dense and difficult points - those that, thanks to the thickness of the paper, hurt the fingers - to get to cut, to free, to finish."

Italian Cover of Things We Didn't Talk About When I Was a GirlThe Italian cover of Things We Didn't Talk About When I Was a Girl is my favorite cover out of the translated versions of this book. The idea of the sewn mouths that slowly free themselves and rediscover the freedom to speak comes from artist/illustrator Camilla Ronzullo, who made the mouths with colored paper, black thread, scissors and needle: "I liked the idea of tightening these mouths with such a symbolic gesture as that of sewing. It was nice for me too, after the fatigue of the dense and difficult points - those that, thanks to the thickness of the paper, hurt the fingers - to get to cut, to free, to finish." -

Excerpt from Interview TranscriptHIM: I remember knowing that I shouldn’t be doing this and doing it anyway. And then I remember you started to cry and then I lay down. There was a little gap where I lay down and then I remember thinking maybe you were so drunk you wouldn’t remember it, or that it was bad and then maybe it would be okay, and then you did start to cry and I remember you whispering, He raped me. And I realized that it wasn’t going to be okay. And then it’s just however many hours of just me realizing what I had just done and that it wasn’t going to be okay.

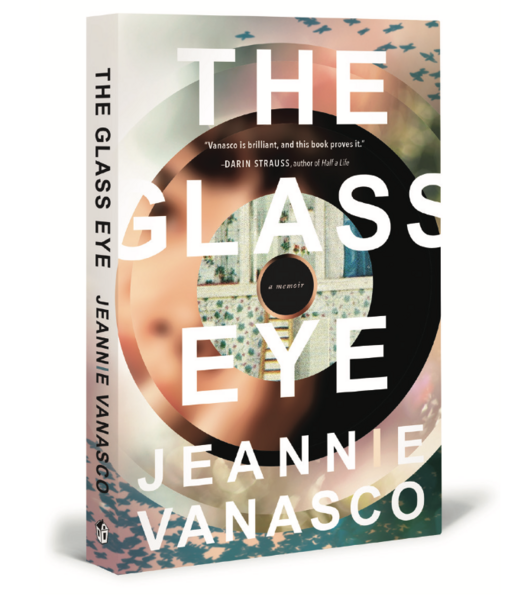

The Glass Eye: A Memoir

Indies Introduce Pick

Barnes & Noble Discover Great New Writers Pick

Poets & Writers's "Five Best Literary Nonfiction Debuts of 2017"

A Fall 2017 Pick at Powell's, Ploughshares, NYLON, Publishers Weekly, Entertainment Weekly, Amazon, Bustle, New York, Newsweek, and more.

Also featured at The Rumpus, Lit Hub, Powell's, Bustle, and more.

Published by Tin House Books in the US. Published by Duckworth Books in the UK.

The night before my dad died, I promised him I would write a book for him. I was eighteen. He was eighty. He was under so much morphine I doubt he heard me. Still, he always kept his word and I wanted to keep mine. But The Glass Eye isn’t the book I imagined. The Glass Eye is my struggle to honor my dad, my larger-than-life hero but also the man who named me after his daughter from a previous marriage, a daughter who died. After his funeral, I spent the next decade in escalating mania, in and out of hospitals―increasingly obsessed with my namesake, Jeanne, and my deathbed promise to my dad.

Because of my obsession with the promise, each of the twenty-one chapters includes an introductory section that references the writing of the book as I’m writing it. Within each chapter there are brief scenes organized under four headings: Dad, Mom, Jeanne, and Mental Illness. This structure allowed me to move back and forth in time, capturing the elliptical and fragmentary nature of my mania and my grief. I wasn’t interested in constructing an arc the way one traditionally constructs plot in narrative writing. Life almost never happens that way, unless the experience is human-made. I wanted a different type of order, not a narrative of my experiences but a narrative of myself, the ways I perceived and processed my experiences.

The Glass Eye's structure took several years to figure out. When first drafting the memoir, I focused almost entirely on my grief for my dad. But the more I wrote, the more I realized that his grief for Jeanne influenced how I grieved for him. That’s when I embraced a sort of sonic logic: eye, i, I. My dad’s glass eye, the letter “i” that my dad added to my name, and the first-person “I.” I began seeing the structure as an equation of loss: eye + i = I. So I pieced together scenes based on that equation: a woman painting my dad’s eye, me seeing a photo of Jeanne for the first time, me hallucinating that my eyes had fallen out, and so on. The manuscript became impressionistic—scene after scene after scene—but tonally cold. There was no “why” holding the scenes together. Also, I had not included enough of my mom, and I felt very bad about that—because she lost him too.

One scene I could not get out of my head: my mom throwing herself over my dad’s coffin. I knew that the book also needed to be about her grief. So then I started organizing the scenes into binders and adding sections that reflected on those scenes. I labeled each binder: Dad, Mom, Jeanne, and Mental Illness. The scene of the woman painting my dad’s eye, that obviously went in the Dad binder. My mom throwing herself over his coffin, that went in the Mom binder. Me seeing Jeanne’s photo, the Jeanne binder. Scenes of my hallucinations, those went in the Mental Illness binder. I didn’t see myself outside of my mental illness, which was a problem—emotionally and on a craft level. Otherwise, though, the binders were great—because I could physically move scenes around, finding artful juxtapositions and new meanings.

The binder system worked well until I visited Jeanne’s grave for the first time. That happened the same month as the ten-year anniversary of my dad’s death. I came back from that visit and started shuffling around my written scenes, color-coding my memories, seeing too many connections between descriptions of my dad, Jeanne, and my psychotic episodes. Suddenly I didn’t know which memory to put in which binder. When you see connections everywhere, you see connections nowhere. Pretty soon I ended up in the hospital. I told a doctor there, "I can't figure out my narrative present." Say it in a writing class, and yeah, it makes perfect sense. Say it in the psych ward, and you've just added an involuntary week to your stay.

It wasn’t until after Masie Cochran at Tin House read my book proposal, three years later, that the story’s shape emerged. On our first call, Masie said: “What if the binders were the structure?” In my sample pages, I’d described the binders, how and why I used them, but they appeared within the narrative—as opposed to organizing the narrative. I knew at that point that Masie was “the one.” After we hung up, I asked my agent to pull the manuscript from everyone else.

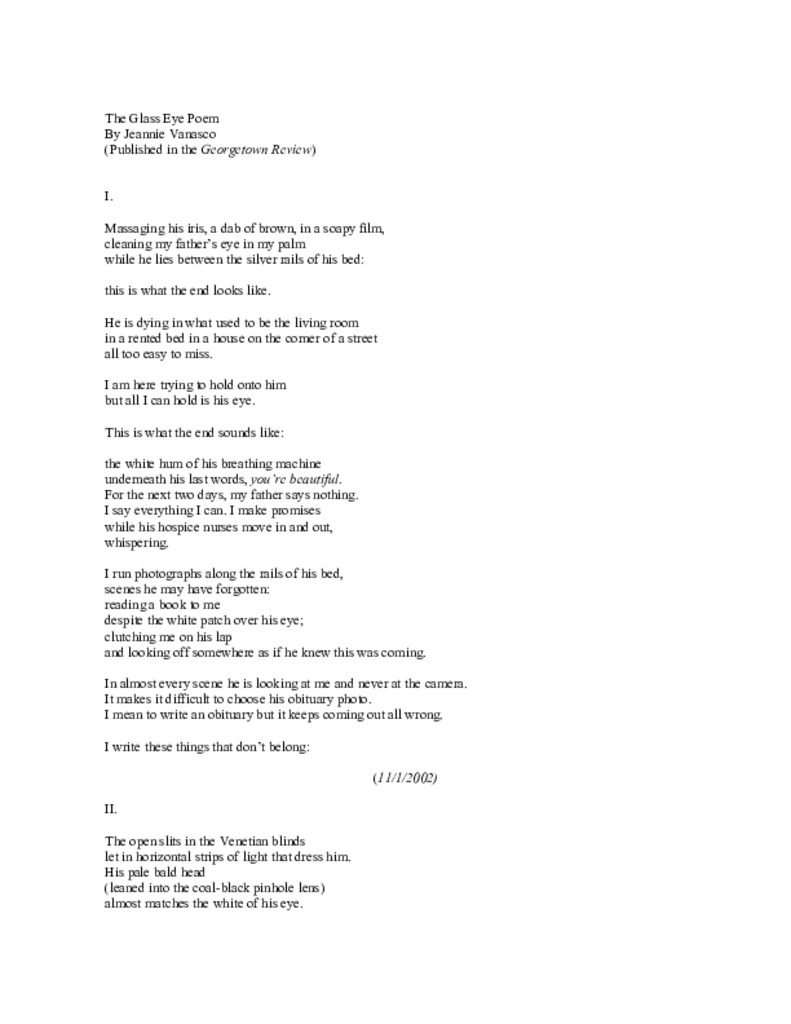

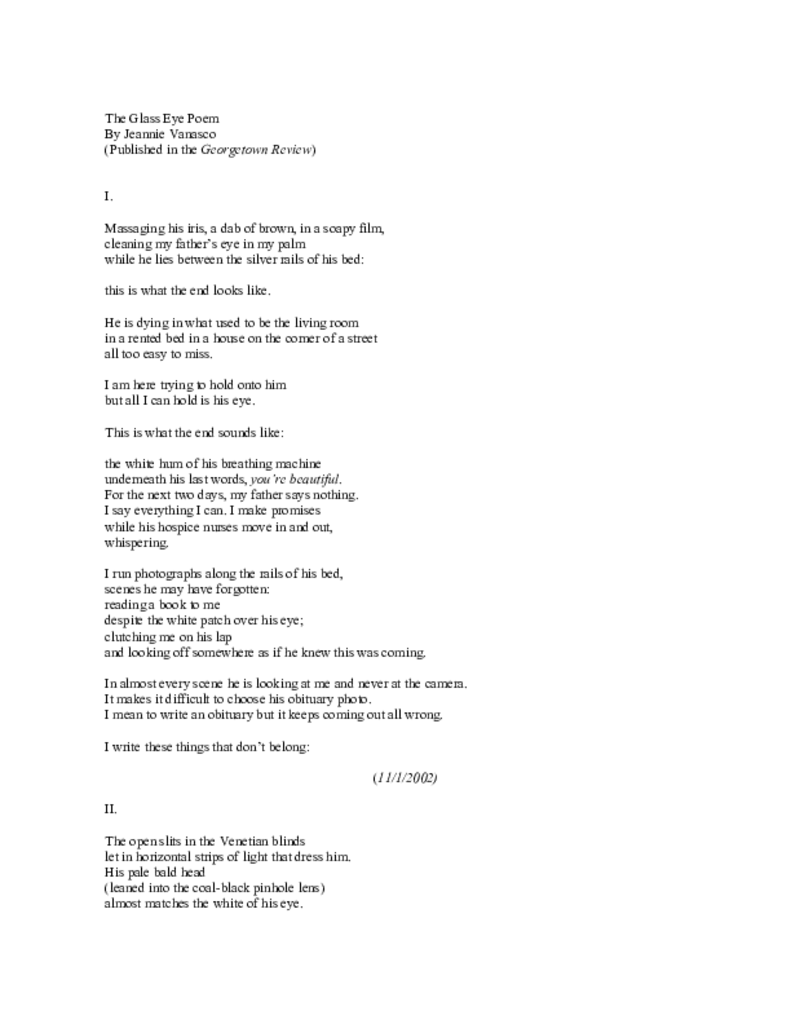

The Glass Eye began as a poem. To read the poem, please click here or click on the first yellow square in this project section.

To read the first three chapters and the opening to chapter four, please click here or click on the second yellow square in this project section.

To watch and/or listen to me read from The Glass Eye, please click here or click on the blue square in this project section.

To read or listen to interviews about The Glass Eye and my latest book, please click here.

-

Reading from THE GLASS EYE at University of Chicago; Jan 12, 2017I was the University of Chicago’s “New Voice in Nonfiction” for 2017. Past New Voices have included Eula Biss, Ander Monson, Joshua Bearman, among others.

-

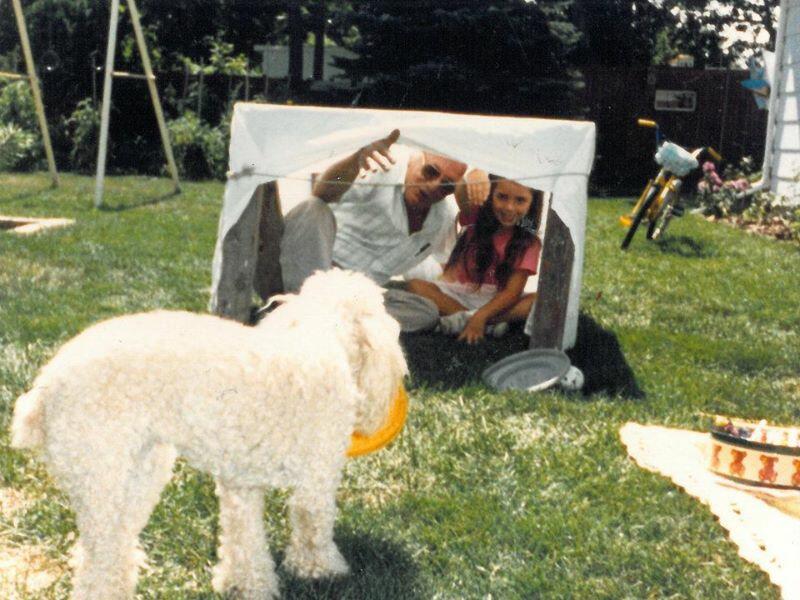

Photograph of my dad and me in our backyard in 1989This is a photograph of my dad and me in a makeshift tent in our backyard in 1989. I looked at this whenever I needed inspiration to keep working on the book.

Photograph of my dad and me in our backyard in 1989This is a photograph of my dad and me in a makeshift tent in our backyard in 1989. I looked at this whenever I needed inspiration to keep working on the book. -

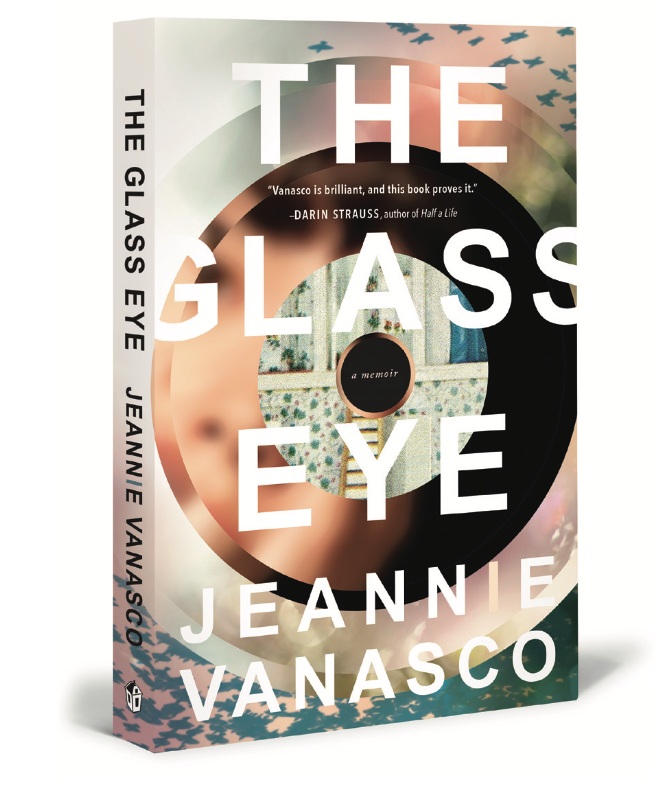

The Glass EyeCover of The Glass Eye. Featured by Poets & Writers as one of the five best literary nonfiction debuts of 2017, The Glass Eye was also selected as a Barnes & Noble Discover Great New Writers Pick, an Indies Introduce Pick, and an Indie Next Pick.

The Glass EyeCover of The Glass Eye. Featured by Poets & Writers as one of the five best literary nonfiction debuts of 2017, The Glass Eye was also selected as a Barnes & Noble Discover Great New Writers Pick, an Indies Introduce Pick, and an Indie Next Pick.

A Silent Treatment (forthcoming)

After moving in with me five years ago, my mom began using the silent treatment at any perceived slight. Her shortest period of silence lasted two weeks. Her longest, almost six months. “I don’t know why I do it,” she told me.

Her silences are a way into the book's narrative, but overwhelmingly the book explores her childhood and adulthood, which offer insight into why she didn't consider silence abusive. (Her mother beat her, threw a knife at her. Her first husband beat her; one of the beatings was so bad she miscarried. He repeatedly called her “worthless” and “stupid.” Those were clear instances of abuse.) As a child, my mom used to hide in the attic and write stories. “I liked to write,” she said, “but nobody ever encouraged me.” I am writing this book to encourage her and better understand her. I also want to write about her life before I was born, as I can think of no other way to accurately describe how her silences made me feel: as if I didn’t exist.

A Silent Treatment is under contract with Tin House, the publisher of my first two books.

Personal and Cultural Essays for the Believer

Selected Essays

"What's in a Necronym?" (first appeared in the Believer; reprinted in Spanish in El Malpensante; reprinted in Italian in Black Coffee; named a Notable Essay in Best American Essays; featured by Longreads)

"Absent Things As If They Are Present" (first appeared in the Believer; reprinted in French by Editions Inculte; anthologized in Read Harder; featured by Longform)

"The Glass Eye: On Seeing and Artificial Eyes" (first appeared in the Believer; featured by Longform; named a Notable Essay in Best American Essays)

"Location, Location, Location: A Brief Personal History of House Moving" (first appeared in the Believer; featured by Longform and Longreads)

-

Absent Things As If They Are Present"Absent Things As If They Are Present" is the first essay I wrote for the Believer. It explores the history of erasure literature and touches on everything from Romantic poetic theory, 19th-century copyright law, and Thomas Jefferson's erasure of The Bible. It first appeared in the Believer. It was soon reprinted in French by Editions Inculte, anthologized in Read Harder, and featured by Longform.

-

What's in a Necronym"What's in a Necronym" explores the experience of being named after a dead sibling. The essay also includes stories about artists named after dead siblings. First published in the Believer, "What's in a Necroynm?" was reprinted in Spanish in El Malpensante, reprinted in Italian in Black Coffee, named a Notable Essay in Best American Essays, and featured by Longreads.

Nothing Unusual to Report: Poems

I have received fellowships and awards for the poems, such as the Emerging Poets Fellowship from Poets House in New York City, and an Amy Award from Poets & Writers magazine.

The first poems that I wrote for this collection appeared in Little Star. To read them, please click here or click "View Full Document" on the box below. "Agency," one of the poems I wrote while an Emerging Poets Fellow at Poets House, can be read here.

"The Dictator Declares War," which appeared in Prairie Schooner and is the collection's opening poem, can be read here or by clicking on the second brown square on the right.

-

Poems in Little StarThese are the first poems that I wrote for Nothing Unusual to Report: "Attention All Students," "The Chamber," "Classified," "The Blasphemer," and "The Dictator Takes to His Telescope." They appeared in Little Star, an annual poetry magazine edited by Ann Kjellberg. They also received an Amy Award from Poets & Writers.

Book Reporting for The New Yorker

"Achieving a Trance State with Madison Smartt Bell"

"Why Is the US Government Interested in Storytelling?"

"National Poetry Month: Coming to You by Plane, Train, and Ferrari"

"A Double Whammy at Tibor de Nagy"

"Mermaids Behaving Badly: Matthea Harvey at the Brooklyn Phil"

(Full Archive at NewYorker.com)

Reviews of Things That Are Not Books

Book Reviews and Author Interviews

Selected Interviews

With Melissa Faliveno (Believer)

With Gina Nutt (Believer)

With Madeleine Watts (Believer)

With Jenn Shapland (BOMB)

With Betsy Bonner (Lit Hub)

Selected Reviews

"Method Writing" (New York Times Book Review)

"Emily's Lists" (Times Literary Supplement)

"On Elizabeth Bishop's Brazil" (Tin House)

"Pierre Martory's 'Landscapist'" (Words Without Borders)