Work samples

-

From the Baltimore Book of the DeadSince 2005, I've been working on a project of memorializing people (as well as certain places and animals) who have touched my life. These are published in three books, The Glen Rock Book of the Dead, The Baltimore Book of the Dead, and The Big Book of the Dead. The pieces are all 400 words or less — there are 125 altogether, so far. The sample here includes the introduction to the Baltimore book, and several of the individual portraits, including both my mother and Prince.

-

"Bohemian Rhapsody" column on Baltimore FishbowlSince May 2011, I've posted 168 personal essays at the Baltimore Fishbowl site, and since 2019, I've illustrated the essays with watercolor paintings. Here's "The Writing Teacher, The Drama Teacher, His Wife, and Their Babysitter: Yet Another American Crime Story," which features a writing student of mine who has had a rather fraught relationship with Monica Lewinsky.

About Marion

Baltimore City

Marion Winik is the author of The Big Book of the Dead, First Comes Love, Above Us Only Sky and many other books of memoir and personal essays. Her award-winning Bohemian Rhapsody column appears monthly at BaltimoreFishbowl.com, and her essays have been published in The New York Times Magazine, The Sun, and elsewhere. She writes book reviews for … more

Jump to a project:

Bohemian Rhapsody essays

Every month for 12 years now, I've posted a personal essay on the Baltimore Fishbowl. The column is called "Bohemian Rhapsody," and it's billed as "a writer's life in Baltimore, where it's never too late to be a work in progress."

You can see the full archive and read any and all of the columns at this link:

http://www.marionwinik.com/work_bohemianrhapsody.html

This one was nominated for a Pushcart Prize

https://baltimorefishbowl.com/stories/things-one-does-not-expect/

Here's a very recent one, musing on trigger warnings:

https://baltimorefishbowl.com/stories/trigger/

You can see the full archive and read any and all of the columns at this link:

http://www.marionwinik.com/work_bohemianrhapsody.html

This one was nominated for a Pushcart Prize

https://baltimorefishbowl.com/stories/things-one-does-not-expect/

Here's a very recent one, musing on trigger warnings:

https://baltimorefishbowl.com/stories/trigger/

The Weekly Reader podcast

The Weekly Reader is a radio show and podcast based at WYPR and produced by my-cost, Lisa Morgan. Every week, I recommend two great books, culled from the reviewing I do for many media outlets. You can listen to past shows here, at the NPR website:

https://www.npr.org/podcasts/554215648/the-weekly-reader

One quick sample show is attached here.

https://www.npr.org/podcasts/554215648/the-weekly-reader

One quick sample show is attached here.

I Know About A Thousand Things

I KNOW ABOUT A THOUSAND THINGS, The Writing of Uvalde's Ann Alejandro, edited by the poet Naomi Shihab Nye and the essayist Marion Winik, is an extraordinary collection of writing put together by two longtime literary friends in tribute to a third. Ann Alejandro, who lived all her life on a ranch in Uvalde, Texas, was a writer of extraordinary natural talent and prolificity. Though Ann would have loved to be widely read and appreciated, she had little interest in scaling the walls of the publishing world and little patience for editing. Thus her chosen form was the letter and her audience close friends and family, plus these two writers. For decades, the pages continued to pour out, blending observation, storytelling, humor, praise, and accounts of her deep attachment to the land and animals that surrounded her in rural Texas.

Having struggled since the age of 30 with severe chronic pain and other health issues, Ann died in 2019 at the age of 64. Before her death, Naomi and Marion promised her they would pull together a book from thousands of pages left in their care. They selected the very best of Ann Alejandro — vignettes, anecdotes, rants, gems of description, and more — and organized it into chapters like Faith, Motherhood, Land, Snakes, Pain, and Love.

This is my Afterword to the collection, which is currently under review at Texas A&M Press.

Afterword

by Marion Winik

When Naomi and I started going through Ann's writing in 2018, and a few years later, as I drafted the first version of our book proposal, I had a certain way to explain the project to people. I would describe the decades of correspondence, the mountains of letters and emails and Facebook posts and manuscripts Ann produced in her life. I would say that I thought of her as an "outsider writer," sort of like the outsider artists in Baltimore's American Visionary Art Museum. I would report her enthusiasm for our book idea, and the little dust-up about Naomi's brainstorm for the cover art that led to Ann's tart suggestion that we publish posthumously. I always included the fact that she was a profoundly Texas-y writer, from a little place in South Texas you never heard of.

That last bit changed on Tuesday, May 24th, 2022 when Uvalde became a place everyone has heard of, the same way they've heard of Columbine, Sandy Hook, Parkland, and Aurora. As the news came in, even before we knew that Ann's ten-year-old great-niece Layla Salazar was among the lost, it crossed both of our minds that it was a blessing Ann didn't live to see this. How could she have borne it? On the other hand, she would have had so much to say about it. Interestingly, as we continued sifting through the material in the months after the shooting, it seemed she already had said some of these things.

Her writing about grief and loss, about civility as a response to dischord, her struggle with faith in the face of terrible pain all seemed to have a new resonance. At the same time, it was as if the true original nature of Uvalde, the little place in South Texas hardly anybody ever heard of, with its feral pigs and greenjays and mules and families celebrating Christmas, was preserved in amber by her writings about it.

We had always planned for me to come down so we could visit Uvalde together and meet with Ann's husband Joe. I wanted to see the places that were important to her, particularly the ranch that was at the center of her life since childhood. I already had a plane ticket to fly down this past summer when the tragedy occurred in May. Should we still go? Of course we should. It was more important than ever, really.

Luckily we arrived in Uvalde after the hordes of media and other doom-related visitors had departed. The town had returned to what I imagined was its normal level of traffic and commotion (i.e., mostly wind and birdsong.) Yet the sorrow was everywhere you looked, from the Welcome to Uvalde sign on the edge of town, to the grounds of the elementary school, to the town square, all marked with crosses, heaped with stuffed animals and withered bouquets, posted with scrawled notes and printed signs of support from police and fire departments and school districts all over Texas and beyond. Downtown, there were stencils of angels in the shop windows alongside the brand-new Children's Bereavement Center. The old-fashioned ice cream parlor and gaily-colored candy store whispered the names of their missing patrons. Even the sign for a flooring distributor called Fresh Start Decoration seemed aware of the discouraging odds.

Around many corners of downtown, in hidden alleys, overlooking empty lots, muralists from all over the state were painting the beautiful shining faces of the 21 victims. Near our Airbnb, a sparkling whitewashed refuge in the oldest building in town, an artist on a scaffold and her assistant worked through the night.

Locals were surprised, and then pleased, that we had actually shown up to talk about something else. Something else! We started with Mendell Morgan, the 81-year-old city librarian whom Naomi had first met when she came to put on the first in series of healing workshops with artists and writers at the library. We joined Mendell for lunch at a place called Oasis Outback. Like a truck stop, Oasis Outback had a huge gift shop that led into multiple capacious paneled dining rooms. All were festooned with the heads of 30-point bucks, bobcats and other taxonomied critters. The tables were full of what looked like the entire population of Uvalde and the surrounding region. It seemed to be the official cafeteria of the town, frequented by law enforcement, large families, and ladies who lunch alike. Its soup and salad bar was the living image of "Texas sized" and featured the most generous definition of salad imaginable, which in this case included numerous desserts. Mendell, however, forswore these postprandial options and ordered all three of us cups of the soft-serve chocolate-and-vanilla-swirl ice milk, which had the magical quality of seeming to come from all three of our very different childhoods. Naomi and I insisted we'd split a cup then found our spoons dueling over the last bite.

We fell so in love with Mendell, who moved back from San Antonio to his hometown after his wife's death twelve years ago, that we also had dinner with him that night and breakfast the next day. He took us to a palatial and brilliantly air-conditioned bank where former governor Dolph Briscoe's art collection was hung for public viewing. Chandeliers dangled over upholstered red leather club chairs and rockers, welcoming the weary public. Along the way, we dreamed up ever more elaborate events and parties to have upon the publication of Ann's book, which could possibly come out around the one-year anniversary of the tragedy, offering that soft promise of something else, something more.

In the gift shops along Main Street we met Ann's old neighbors, the daughter of one of her classmates — we met no one who didn't know who she was. But every time Naomi and I introduced ourselves and explained our project, I had to add that actually, I never met her. Even Naomi was surprised by this. But it's a fact. I never did. Naomi started forwarding Ann's letters to me in the late nineties, and cc'ing her on my responses, which led to her including me on her to-lists and eventually anointing me as one of the editors of her hopefully posthumous book. I am pretty sure we never even spoke on the phone. But here I am.

The surprisingly youthful and good-humored Joe Alejandro, Ann's husband of forty-five years, arrived in his truck to take us out to the ranch, hoping also to meet Ann's son Dylan and his wife Jennifer who live there now. He had brought all their old photo albums for us to look at, and was happy to tell all the stories we wanted to hear. How they met in high school, at 18 and 17, and married a year later, the interracial alliance so upsetting that some of Ann's aunts wrote her father Herbie begging him to put his foot down. (Nobody seemed to mind that they were so young.) Joe talked alot about his father-in-law Herbie Toombs — the men were clearly close, allied by their interests in farming, home improvement and golf. Later that night, out for a drink with our librarian friend, Joe would teach me to order a gin-and-tonic Herbie Toombs style -- a double shot of Bombay Sapphire in a short glass. On some subjects, I can be a fast learner.

The dirt road leading into the ranch through acres of scrubland seemed very long, more than the three miles Joe said it was. But as soon as we passed through the gate, we were greeted by a mama cow and her calf. You came to see animals? they seemed to say. Well, here we are. Nearby, a number of longhorn bulls grazed, surveying their patrimony, not straying too far from the water tank which is probably all that's keeping them and the deer, the ocelots and the coyotes, the ducks and the geese, even the jackrabbits going in the drought that has been going on for years now. Twelve years, by some counts I find online.

We went up to the little graveyard I knew well from Ann's writing, where the green jays sang at her mama's funeral, where Ann herself is now buried alongside her beloved brother Lee and her parents and grandparents. Joe sat in the rusty swing, his head bowed. After a while, he told us that he plans to dig his own hole next to Ann, "so my boys won't have to do it." But that time seemed a long way off. After another while, Joe's phone buzzed with a message from Dylan, the older of his and Ann's sons, telling him to bring us on up to the house.

Though we were told the house in question was carted onto the land in flatbed trucks after the original house, built on the highest spot on the property, burned down during a wild lightning storm on Sunday, May 28th, 2017. It looked completely natural in its wooded setting. Past the large wooden deck, a sprinkler waved prisms of water beneath the lowest branches of the loblolly pines. "What are you watering?" I asked Jennifer.

"The dirt," she said. "To keep it on the ground." Then she took me in the house to introduce me to her nine cats and pour me a glass of deliciously cold red wine. She showed me a picture of her daughter Kaitlyn at her high school graduation earlier this year. She is holding a certificate which declares her the winner of the Ann Toombs Alejandro scholarship for creative writing, which she is now putting to good use at one of the branches of Texas A&M. Another writer in the family. Granny Annie, as they called her, would love that.

In the hour we spent on the porch with Dylan, Jennifer and Joe, I understood for the first time that not only Layla Salazar but also the boy who murdered her and her classmates and teachers is a blood relation of this extended family. The hurt is too much to hold. It curdles to anger, roils and rages inside him. The sense that this place, his place, his home, has been irredeemably altered and he couldn't stop it and no one else stopped it, is almost unbearable. Here on the ranch, even, the violation makes itself felt.

Dylan and his father feel very strongly about guns: they can't imagine a life without them. Naomi and I know this. We know that Joe has a gun in the truck right now. When we were editing Ann's letters, we read pages and pages of proud pro-gun sentiment, some of it specifically in reaction to the Columbine shooting. In my younger years, I likely would have felt compelled to bring this up with the Alejandro men. In my seventh decade, I have the sense to just listen.

Then suddenly, it was 8:23. "You better go or you'll miss it," Dylan said. He knew I was hoping to see a ranch sunset, something Ann had written about many times. We offered quick goodbyes and thanks and promises to return, then ran to the truck, and Joe somehow got us to the top of the hill where the main house used to be in negative two minutes, just in time. The original stone fireplace still stood, alongside two small rooms Joe put up and lived in for a while. There were several rusty barbecue smokers. And there was the big Texas sky, ribboned with peach as the burning ball disappeared at the close of the day.

As Ann put it, and to give her the last word --

Chess Pie and I go to a world without words; at sunset there is a rounding road on a hill from which we can see not a sign of any human at all, only the bowl of sky equaled to the earth around us. We can see southwest to the clouds forming on the Gulf of Mexico that will bring us the wind in the evening; we look north and we can see the Uvalde water towers, Mount Inge, the hills at Knippa, and the hills of all three rivers which spill into the valleys — the Nueces, the Frio, and the Sabinal.

Every sunset, every flower or field of flowers, every cactus, every river and drought, with 117 degrees going on for days straight, it will be part of me. All the names of all the plants and trees and grasses I will know like my own. On summer evening breezes, I will smell the Gulf surf 200 miles away.

Someday I will be almost whole.

Having struggled since the age of 30 with severe chronic pain and other health issues, Ann died in 2019 at the age of 64. Before her death, Naomi and Marion promised her they would pull together a book from thousands of pages left in their care. They selected the very best of Ann Alejandro — vignettes, anecdotes, rants, gems of description, and more — and organized it into chapters like Faith, Motherhood, Land, Snakes, Pain, and Love.

This is my Afterword to the collection, which is currently under review at Texas A&M Press.

Afterword

by Marion Winik

When Naomi and I started going through Ann's writing in 2018, and a few years later, as I drafted the first version of our book proposal, I had a certain way to explain the project to people. I would describe the decades of correspondence, the mountains of letters and emails and Facebook posts and manuscripts Ann produced in her life. I would say that I thought of her as an "outsider writer," sort of like the outsider artists in Baltimore's American Visionary Art Museum. I would report her enthusiasm for our book idea, and the little dust-up about Naomi's brainstorm for the cover art that led to Ann's tart suggestion that we publish posthumously. I always included the fact that she was a profoundly Texas-y writer, from a little place in South Texas you never heard of.

That last bit changed on Tuesday, May 24th, 2022 when Uvalde became a place everyone has heard of, the same way they've heard of Columbine, Sandy Hook, Parkland, and Aurora. As the news came in, even before we knew that Ann's ten-year-old great-niece Layla Salazar was among the lost, it crossed both of our minds that it was a blessing Ann didn't live to see this. How could she have borne it? On the other hand, she would have had so much to say about it. Interestingly, as we continued sifting through the material in the months after the shooting, it seemed she already had said some of these things.

Her writing about grief and loss, about civility as a response to dischord, her struggle with faith in the face of terrible pain all seemed to have a new resonance. At the same time, it was as if the true original nature of Uvalde, the little place in South Texas hardly anybody ever heard of, with its feral pigs and greenjays and mules and families celebrating Christmas, was preserved in amber by her writings about it.

We had always planned for me to come down so we could visit Uvalde together and meet with Ann's husband Joe. I wanted to see the places that were important to her, particularly the ranch that was at the center of her life since childhood. I already had a plane ticket to fly down this past summer when the tragedy occurred in May. Should we still go? Of course we should. It was more important than ever, really.

Luckily we arrived in Uvalde after the hordes of media and other doom-related visitors had departed. The town had returned to what I imagined was its normal level of traffic and commotion (i.e., mostly wind and birdsong.) Yet the sorrow was everywhere you looked, from the Welcome to Uvalde sign on the edge of town, to the grounds of the elementary school, to the town square, all marked with crosses, heaped with stuffed animals and withered bouquets, posted with scrawled notes and printed signs of support from police and fire departments and school districts all over Texas and beyond. Downtown, there were stencils of angels in the shop windows alongside the brand-new Children's Bereavement Center. The old-fashioned ice cream parlor and gaily-colored candy store whispered the names of their missing patrons. Even the sign for a flooring distributor called Fresh Start Decoration seemed aware of the discouraging odds.

Around many corners of downtown, in hidden alleys, overlooking empty lots, muralists from all over the state were painting the beautiful shining faces of the 21 victims. Near our Airbnb, a sparkling whitewashed refuge in the oldest building in town, an artist on a scaffold and her assistant worked through the night.

Locals were surprised, and then pleased, that we had actually shown up to talk about something else. Something else! We started with Mendell Morgan, the 81-year-old city librarian whom Naomi had first met when she came to put on the first in series of healing workshops with artists and writers at the library. We joined Mendell for lunch at a place called Oasis Outback. Like a truck stop, Oasis Outback had a huge gift shop that led into multiple capacious paneled dining rooms. All were festooned with the heads of 30-point bucks, bobcats and other taxonomied critters. The tables were full of what looked like the entire population of Uvalde and the surrounding region. It seemed to be the official cafeteria of the town, frequented by law enforcement, large families, and ladies who lunch alike. Its soup and salad bar was the living image of "Texas sized" and featured the most generous definition of salad imaginable, which in this case included numerous desserts. Mendell, however, forswore these postprandial options and ordered all three of us cups of the soft-serve chocolate-and-vanilla-swirl ice milk, which had the magical quality of seeming to come from all three of our very different childhoods. Naomi and I insisted we'd split a cup then found our spoons dueling over the last bite.

We fell so in love with Mendell, who moved back from San Antonio to his hometown after his wife's death twelve years ago, that we also had dinner with him that night and breakfast the next day. He took us to a palatial and brilliantly air-conditioned bank where former governor Dolph Briscoe's art collection was hung for public viewing. Chandeliers dangled over upholstered red leather club chairs and rockers, welcoming the weary public. Along the way, we dreamed up ever more elaborate events and parties to have upon the publication of Ann's book, which could possibly come out around the one-year anniversary of the tragedy, offering that soft promise of something else, something more.

In the gift shops along Main Street we met Ann's old neighbors, the daughter of one of her classmates — we met no one who didn't know who she was. But every time Naomi and I introduced ourselves and explained our project, I had to add that actually, I never met her. Even Naomi was surprised by this. But it's a fact. I never did. Naomi started forwarding Ann's letters to me in the late nineties, and cc'ing her on my responses, which led to her including me on her to-lists and eventually anointing me as one of the editors of her hopefully posthumous book. I am pretty sure we never even spoke on the phone. But here I am.

The surprisingly youthful and good-humored Joe Alejandro, Ann's husband of forty-five years, arrived in his truck to take us out to the ranch, hoping also to meet Ann's son Dylan and his wife Jennifer who live there now. He had brought all their old photo albums for us to look at, and was happy to tell all the stories we wanted to hear. How they met in high school, at 18 and 17, and married a year later, the interracial alliance so upsetting that some of Ann's aunts wrote her father Herbie begging him to put his foot down. (Nobody seemed to mind that they were so young.) Joe talked alot about his father-in-law Herbie Toombs — the men were clearly close, allied by their interests in farming, home improvement and golf. Later that night, out for a drink with our librarian friend, Joe would teach me to order a gin-and-tonic Herbie Toombs style -- a double shot of Bombay Sapphire in a short glass. On some subjects, I can be a fast learner.

The dirt road leading into the ranch through acres of scrubland seemed very long, more than the three miles Joe said it was. But as soon as we passed through the gate, we were greeted by a mama cow and her calf. You came to see animals? they seemed to say. Well, here we are. Nearby, a number of longhorn bulls grazed, surveying their patrimony, not straying too far from the water tank which is probably all that's keeping them and the deer, the ocelots and the coyotes, the ducks and the geese, even the jackrabbits going in the drought that has been going on for years now. Twelve years, by some counts I find online.

We went up to the little graveyard I knew well from Ann's writing, where the green jays sang at her mama's funeral, where Ann herself is now buried alongside her beloved brother Lee and her parents and grandparents. Joe sat in the rusty swing, his head bowed. After a while, he told us that he plans to dig his own hole next to Ann, "so my boys won't have to do it." But that time seemed a long way off. After another while, Joe's phone buzzed with a message from Dylan, the older of his and Ann's sons, telling him to bring us on up to the house.

Though we were told the house in question was carted onto the land in flatbed trucks after the original house, built on the highest spot on the property, burned down during a wild lightning storm on Sunday, May 28th, 2017. It looked completely natural in its wooded setting. Past the large wooden deck, a sprinkler waved prisms of water beneath the lowest branches of the loblolly pines. "What are you watering?" I asked Jennifer.

"The dirt," she said. "To keep it on the ground." Then she took me in the house to introduce me to her nine cats and pour me a glass of deliciously cold red wine. She showed me a picture of her daughter Kaitlyn at her high school graduation earlier this year. She is holding a certificate which declares her the winner of the Ann Toombs Alejandro scholarship for creative writing, which she is now putting to good use at one of the branches of Texas A&M. Another writer in the family. Granny Annie, as they called her, would love that.

In the hour we spent on the porch with Dylan, Jennifer and Joe, I understood for the first time that not only Layla Salazar but also the boy who murdered her and her classmates and teachers is a blood relation of this extended family. The hurt is too much to hold. It curdles to anger, roils and rages inside him. The sense that this place, his place, his home, has been irredeemably altered and he couldn't stop it and no one else stopped it, is almost unbearable. Here on the ranch, even, the violation makes itself felt.

Dylan and his father feel very strongly about guns: they can't imagine a life without them. Naomi and I know this. We know that Joe has a gun in the truck right now. When we were editing Ann's letters, we read pages and pages of proud pro-gun sentiment, some of it specifically in reaction to the Columbine shooting. In my younger years, I likely would have felt compelled to bring this up with the Alejandro men. In my seventh decade, I have the sense to just listen.

Then suddenly, it was 8:23. "You better go or you'll miss it," Dylan said. He knew I was hoping to see a ranch sunset, something Ann had written about many times. We offered quick goodbyes and thanks and promises to return, then ran to the truck, and Joe somehow got us to the top of the hill where the main house used to be in negative two minutes, just in time. The original stone fireplace still stood, alongside two small rooms Joe put up and lived in for a while. There were several rusty barbecue smokers. And there was the big Texas sky, ribboned with peach as the burning ball disappeared at the close of the day.

As Ann put it, and to give her the last word --

Chess Pie and I go to a world without words; at sunset there is a rounding road on a hill from which we can see not a sign of any human at all, only the bowl of sky equaled to the earth around us. We can see southwest to the clouds forming on the Gulf of Mexico that will bring us the wind in the evening; we look north and we can see the Uvalde water towers, Mount Inge, the hills at Knippa, and the hills of all three rivers which spill into the valleys — the Nueces, the Frio, and the Sabinal.

Every sunset, every flower or field of flowers, every cactus, every river and drought, with 117 degrees going on for days straight, it will be part of me. All the names of all the plants and trees and grasses I will know like my own. On summer evening breezes, I will smell the Gulf surf 200 miles away.

Someday I will be almost whole.

Formal Poetry Project

During the pandemic, I found myself returning to my roots as a writer in poetry, specifically formal poetry: sestinas, villanelles, gloses, pantoums. I wrote this pantoum when my dog died.

A Pantoum for Beau

10/3/2004 - 9/18/2020

You were always here and I was always here,

and if I went away, you went with me.

You never learned to sit but you had your own tricks —

Whatever bad thing happened, you could fix me.

If I went away, and you were rudely forced to stay,

nothing moved you from your spot by the door.

Whatever bad thing happened, you knew right away;

would lick my face, my feet, my cut — then lick some more.

Now the hardest thing is coming in that door.

Also bad: the couch, the yard, the bed.

I drink and read alone, then drink some more.

Even sleep is sad; I wake half-dead.

Who will clean my plate, share my shrimp, my sauce, my bread?

People say you're with Ruth Bader Ginsburg doing fine.

But your treats are here, your beaded leash, your cozy dachshund bed —

Ruth, give him back. He is mine.

You're with E.B. White and Elizabeth Bishop doing fine,

velvet ears, colossal paws, long pink tongue.

We took our pills each morning and went to bed at nine.

It has been a long time since we were young.

Your worried eyes, big black nose, tireless tongue.

For every visitor, so much wagging, so much joy!

How you bounded, ears flying, through the grass when you were young.

I was chopped liver if we had a visitor, fickle boy.

A sixteen-year conspiracy of joy,

a thousand names, made-up words and silly songs.

I still sing them all. Oh my good boy—

How can it be that I am here and you are gone?

The next poem is a Portuguese glose. It usually opens with four lines from another poet, followed by four ten-line stanzas, each of which ends with one of those lines, and in some way comments on them. Within the stanzas, lines 6 and 9 rhyme with the 10th. The first four lines are from Michael Ondaatje’s poem, “To A Sad Daughter.”

For Your Twentieth Birthday, in Quarantine

Want everything. If you break

break going out not in.

How you live your life I don't care

But I’ll sell my arms for you.

Yesterday I learned I have been washing myself wrong

all my life. You don’t put soap in there, Mom. Don’t you know

what that does to the pH of your vagina? My ancient puss

blushed at the attention. All the things you know about

eyebrows, oat milk, white privilege, and I can barely

brush my teeth or read an expiration date. I take

the blame for those pillowcases that made your hair frizz.

Mine was a butch mom; my trousseau, martini olives

and a pile of golf hats. I can still teach you all my best mistakes.

Want everything. If you break

the butter dish or the dachshund statue, get out the crazy

glue, start writing. Potential embarrassment is no reason

to leave a door unopened. Don’t be shy, don’t be afraid

to raise your hand. Give the answer, place your order,

tell the waitress, tell the teacher, tell that icky man

to go away. Do you need me to say this? You always win

at cards, beat me at Scrabble. You know, and you know

you know, and what you don’t know, who knows. They say

it can’t hurt you. But the line between brave and stupid is thin.

Break going out not in.

No college kid in America wanted to come home

when quarantine started, and some didn’t.

You did, miserably, weeping for your sophomore year,

but since then you’ve showed everyone how it’s done.

Nine-minute miles, Wheel and Dancer, granola and yogurt,

protests, TikToks, All Cops Are Bastards. Your hair

stops strangers in the street, exclaiming as if they spied

an adorable pet. I was sad, at first, about the hand-

inked tattoo, but here is something we share:

How you live your life I don't care

What I mean is, I trust you.

I have been making portraits of your self-portraits;

when someone asked if you don’t mind, you had to

laugh. Since the late nineteen-eighties I’ve only

made pictures of children. You popped in twenty

years ago to give your brothers a break. It’s true,

for me, parenting has been one big scam.

Before we open your presents, I’d like to ask Michael

Ondaatje if this is really such a great thing to do.

But I’ll sell my arms for you.

A Pantoum for Beau

10/3/2004 - 9/18/2020

You were always here and I was always here,

and if I went away, you went with me.

You never learned to sit but you had your own tricks —

Whatever bad thing happened, you could fix me.

If I went away, and you were rudely forced to stay,

nothing moved you from your spot by the door.

Whatever bad thing happened, you knew right away;

would lick my face, my feet, my cut — then lick some more.

Now the hardest thing is coming in that door.

Also bad: the couch, the yard, the bed.

I drink and read alone, then drink some more.

Even sleep is sad; I wake half-dead.

Who will clean my plate, share my shrimp, my sauce, my bread?

People say you're with Ruth Bader Ginsburg doing fine.

But your treats are here, your beaded leash, your cozy dachshund bed —

Ruth, give him back. He is mine.

You're with E.B. White and Elizabeth Bishop doing fine,

velvet ears, colossal paws, long pink tongue.

We took our pills each morning and went to bed at nine.

It has been a long time since we were young.

Your worried eyes, big black nose, tireless tongue.

For every visitor, so much wagging, so much joy!

How you bounded, ears flying, through the grass when you were young.

I was chopped liver if we had a visitor, fickle boy.

A sixteen-year conspiracy of joy,

a thousand names, made-up words and silly songs.

I still sing them all. Oh my good boy—

How can it be that I am here and you are gone?

The next poem is a Portuguese glose. It usually opens with four lines from another poet, followed by four ten-line stanzas, each of which ends with one of those lines, and in some way comments on them. Within the stanzas, lines 6 and 9 rhyme with the 10th. The first four lines are from Michael Ondaatje’s poem, “To A Sad Daughter.”

For Your Twentieth Birthday, in Quarantine

Want everything. If you break

break going out not in.

How you live your life I don't care

But I’ll sell my arms for you.

Yesterday I learned I have been washing myself wrong

all my life. You don’t put soap in there, Mom. Don’t you know

what that does to the pH of your vagina? My ancient puss

blushed at the attention. All the things you know about

eyebrows, oat milk, white privilege, and I can barely

brush my teeth or read an expiration date. I take

the blame for those pillowcases that made your hair frizz.

Mine was a butch mom; my trousseau, martini olives

and a pile of golf hats. I can still teach you all my best mistakes.

Want everything. If you break

the butter dish or the dachshund statue, get out the crazy

glue, start writing. Potential embarrassment is no reason

to leave a door unopened. Don’t be shy, don’t be afraid

to raise your hand. Give the answer, place your order,

tell the waitress, tell the teacher, tell that icky man

to go away. Do you need me to say this? You always win

at cards, beat me at Scrabble. You know, and you know

you know, and what you don’t know, who knows. They say

it can’t hurt you. But the line between brave and stupid is thin.

Break going out not in.

No college kid in America wanted to come home

when quarantine started, and some didn’t.

You did, miserably, weeping for your sophomore year,

but since then you’ve showed everyone how it’s done.

Nine-minute miles, Wheel and Dancer, granola and yogurt,

protests, TikToks, All Cops Are Bastards. Your hair

stops strangers in the street, exclaiming as if they spied

an adorable pet. I was sad, at first, about the hand-

inked tattoo, but here is something we share:

How you live your life I don't care

What I mean is, I trust you.

I have been making portraits of your self-portraits;

when someone asked if you don’t mind, you had to

laugh. Since the late nineteen-eighties I’ve only

made pictures of children. You popped in twenty

years ago to give your brothers a break. It’s true,

for me, parenting has been one big scam.

Before we open your presents, I’d like to ask Michael

Ondaatje if this is really such a great thing to do.

But I’ll sell my arms for you.

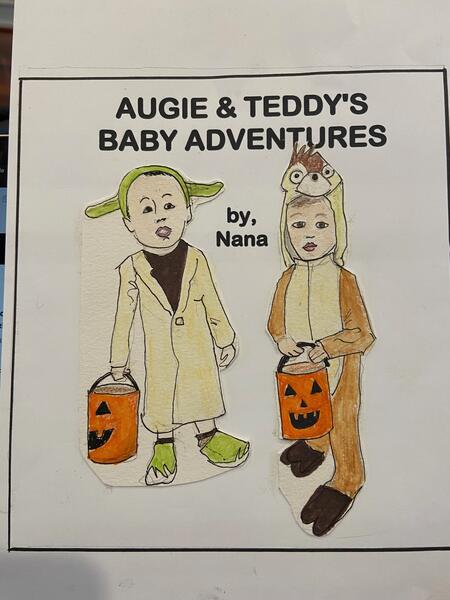

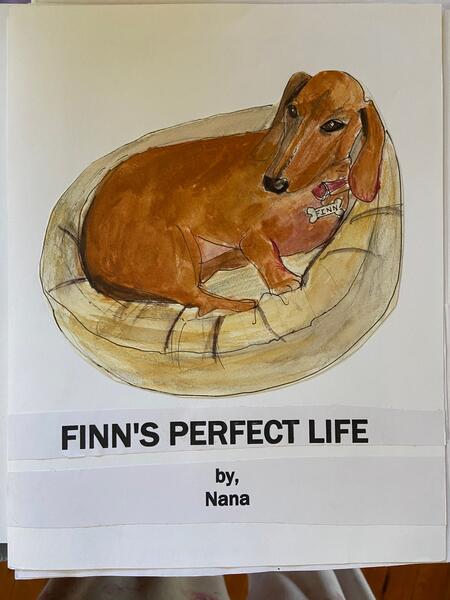

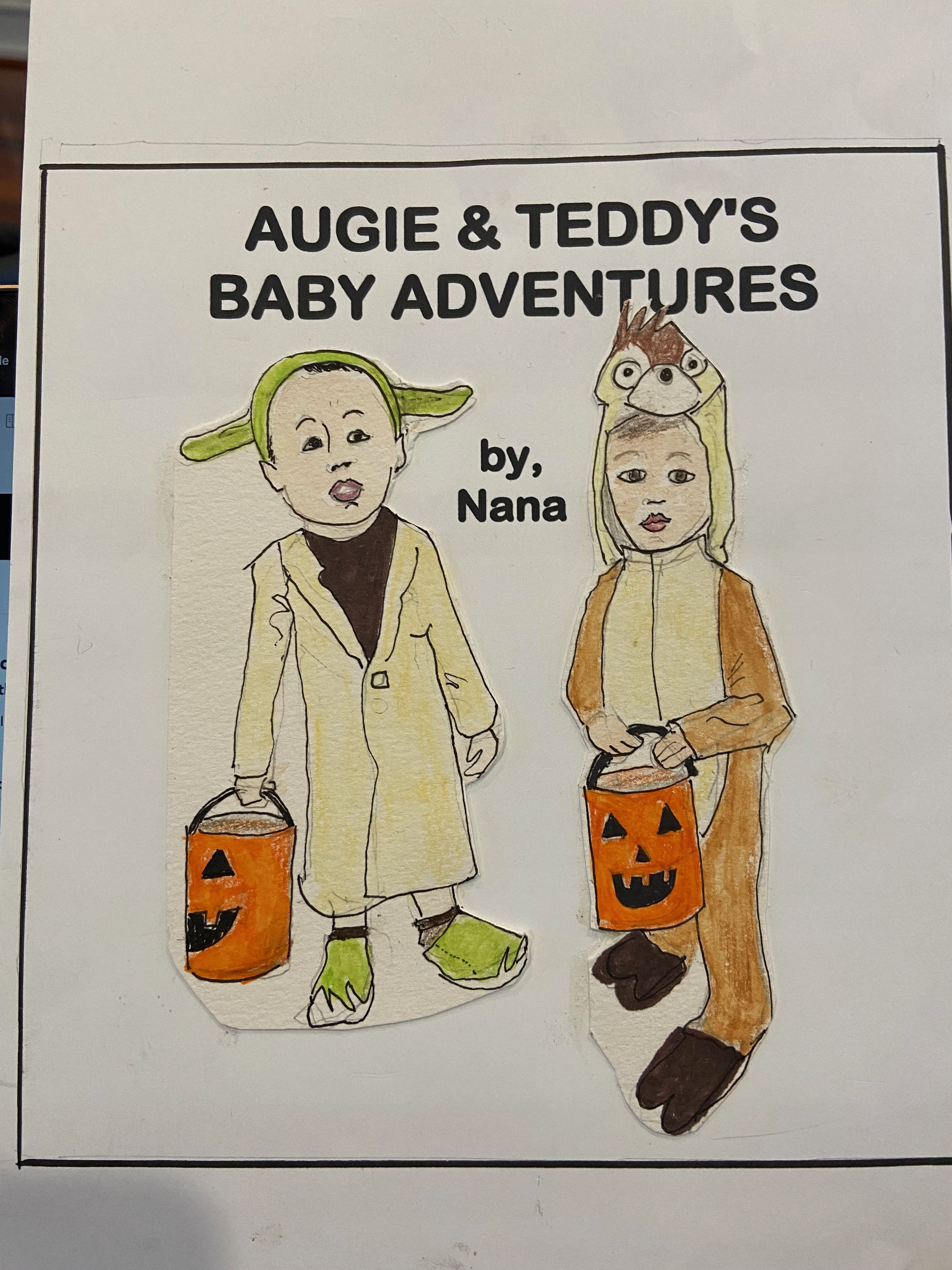

Illustrated Books

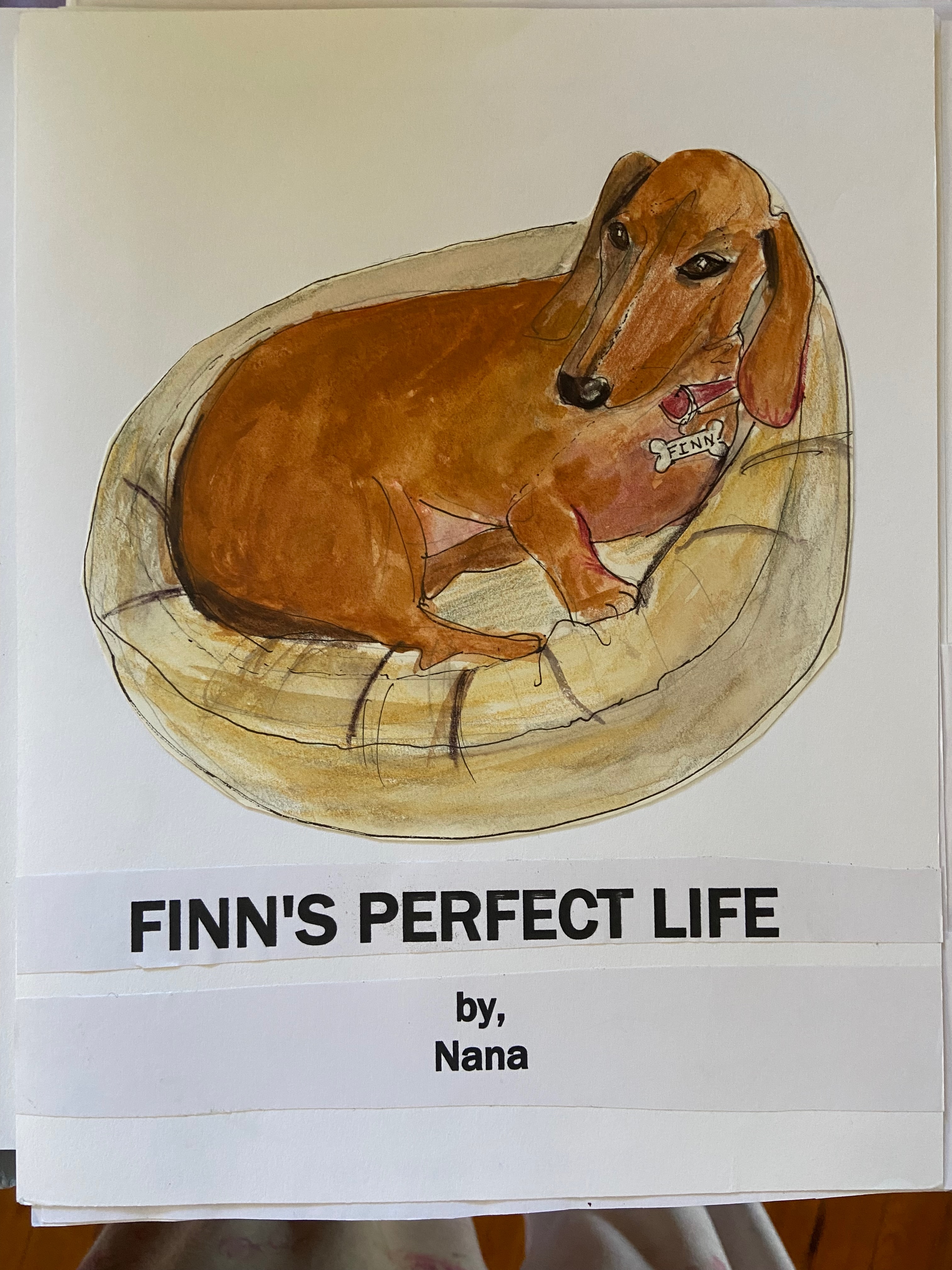

I would love to do an illustrated memoir, and I've been working towards it in various ways, largely with the illustrated columns at the Baltimore Fishbowl. But I've also been working on illustrated children's books. Since my grandson Teddy was born, I've made him "Finn's Perfect Life" and "Teddy and Augie's Baby Adventures."

Novel in Progress

I am working on a novel featuring a widowed advice columnist named Bernie Beller who lives at the Jersey Shore, outside Asbury Park. Bernie has a beautiful home in Deal, which belonged to her late husband's family for generations, and she is a bit of Mrs. Ramsay, Mrs. Ramsay being the Virginia Woolf character who has many houseguests and is known for her gracious hospitality. However, as the novel opens, she takes a fall which seriously injures her beloved dachshund and lands her in the hospital as well. This sounds the alarm for her young adult children, Elliot and Hayley, an investment banker and a yoga teacher respectively. Their mother has not recovered from their father's sudden death during their annual Labor Day party four years ago (and they actually don't know all the details of his death, or that his life insurance policy didn't pay out because of them.) Though Bernie has had a long run as the magazine advice columnist "Ask Athena," she's taken a sabbatical, with the magazine crowd-sourcing the answers to the queries each month. In fact, if she doesn't get back to it, she stands to lose the column altogether, so her longtime editor, Hal Parker, calls to say he is coming down to the Shore to talk to her about it. Also, the kids don't know that Bernie has received a large cash offer for the house, and is seriously considering selling.

I am about 50 pages into this project. The working title is Northern Hospitality.

I am about 50 pages into this project. The working title is Northern Hospitality.