About Jonathan

Tatuamunha • Residency 2017

Please click here for a full description with embedded images

Click here for detailed images.

•

Jonathan spent the month of August as an artist-in-residence in the village of Tatuamunha, Brazil, along the country’s Coral Coast. Through his painting, Jonathan sought to evoke some of the natural and social experiences of daily life in this rural part of the country.

By straining the sand from his beachside residence, Jonathan filtered out everything but the finest-grained black sands to be used as raw materials in his paintings. With a limited palette of black, white, ochre and gray, these sands were used to create a textural and aesthetic reference to the black-washed beaches that result from the receding tides.

In addition to the use of sand, Jonathan incorporated mud, clay and cement in his work in order to allude to the humble mud-brick houses that can still be found in these rural areas of the country. These works - which are not only visually textured but also tactile in their nature - serve as a metaphor for the simplicity and humility that underlies the daily experience of so much of the local population.

Despite the persistence of what might be labeled as the area's ‘underdeveloped existence,’ Jonathan did not create these works to serve as a moral or political statement. Instead, he sees these paintings more as a poetic reference to the individuals who - with hope and humility - continue to find beauty and dignity in the simplicity of their lives.

•

Attempting to move beyond merely aestheticized references to simple homes, Jonathan sought to tie his work more directly to the immediate realities of the local population. To this effort, Jonathan created a painting that would be completed by the house staff at the residence where he lived.The locals who worked on the property were responsible for cooking, cleaning and gardening - typical minimum-wage labor that is characteristic of the area's quickly growing tourism industry. The 'painting' that Jonathan prepared was a nearly-completed work which could have stood alone as a final version. However, this 'completed work' was merely intended to serve as the basis for the remainder of the work that would be carried out by the staff.

Jonathan recruited the gardener to spend some time scrubbing the 'completed painting' in an attempt to remove some of the dried paint. The objective was to make the canvas 'clean' again with the basic tools that the gardener or maid would use for daily work: a hose, dish soap, sponges, laundry detergent, scrubbing brushes, etc.

The involvement of the gardener in the process of creation immediately brings to the fore certain underlying questions. For one, it calls into question the definition of a completed painting - it requires us to grapple with an underlying teleological definition of art-making that presupposes a particular finished product whose development is intended and prescribed by an artist.

The intervention of the gardener on an already 'completed' painting begs the notion of what it means for the work to have been complete in the first place. Under standard definitions, we might be inclined to say that either the painting wasn't finished when the gardener got to it, or he was the one to actually complete it. It is rare that we allow ourselves to think about an artwork as having numerous states of 'finality' that are equally valid.

While the end result of the gardener's intervention might be visually similar in style to the painting's previous state, there is an undeniable shift in the relation of the visual elements that comprise the painting with the actions that created them. As a result of the intervention, the physical canvas becomes more of a dialectical tool than an aestheticized object.

The 'post-dialectic' painting literally embeds the intentions and realities of a person who (by the restrictions of his social and economic status) is likely to live in a home and neighborhood that resembles the fracture and decay that is present in the aesthetic elements of the painting.

As such, the aesthetic elements (which result from the actions of a man who lives in a community that resembles the painting) call into question certain basic relationships that drive and sustain the world we live in. These visual elements begin to unravel relationships such as the value of an artwork vs. the value of a human being (i.e., the value of their time, their labor, their energy, etc.) - especially in light of the fact that the market value of such a painting greatly exceeds the economic power of a low-wage worker.

Despite the fact that the service rendered by the gardener was neither difficult nor time consuming, the basic premise of the social context problematizes the issue of what the appropriate compensation might be for the gardener's assistance. This painting (and the socio-economic dynamics that it intentionally embodies) strives to explicitly highlight this tension - a tension which is often present in works of art, but which is typically overlooked (or ignored) when the art is being admired above a fancy living room sofa, in a board room, or on a gallery wall.

We live in an age where a great number of contemporary artworks are made by assistants - as opposed to the artists who otherwise claim authorship of the work; an age in which an artist often serves more as a director or manager and whose hands may never sculpt a single aspect of a final product.

Who, then, should be named the author of this work?

Many may reply (as did the gardener himself) that the artist bears such rights - in virtue of having created and developed the idea - and that the participation of the of the gardener was merely a mechanical intervention; a basic execution of menial tasks.

However, one might rebut that the artwork could not contain its dialectical significance and value without the participation of the gardener; that the interaction of the gardener is intrinsic to the meaning of the work - regardless of the task that he may have been recruited to carryout.

Although these views may be rooted in competing conceptions of power and authority, the intention of this painting and, more importantly, the context it creates, was not intended to answer this question.

The goal was merely to make visible certain questions that are often suppressed, but which must be addressed. This painting makes these questions undeniable by making the central significance and function of the work to be that of a catalyst and tool for deconstructing itself and the circumstances that produced it - regardless of whether or not it turned out to be aesthetically pleasing.

•

Similarly, Jonathan sought to explore beyond the two-dimensional confines of paint-on-canvas in a work that represents the old and weathered wooden doors and gates that are common to the area. Historically, entryways have not only been used to block or admit access, but as symbols of social status. In this way, doors and gates are often socially loaded objects that represent the status of the people or authorities that reign behind them.

In the case of Tatuamunha, and throughout the entire country, there is a plethora of gates and doors that represent corroded socio-economic dynamics in an aesthetically beautiful way - analogous to the beautifully decaying homes.

However, despite our ability to view the aesthetic beauty of the physical structures, they remain manifestations of dark cultural realities that economically imprison and psychologically undermine those individuals who are constrained to experience such structures as a quotidian reality; Individuals who are not fortunate enough to have the socially-endowed luxury of perceiving them as artistically beautiful.

In order to tie this cultural reality more deeply into his work, Jonathan again requested the help of the gardener, as well as the assistance of a maid on the staff - a woman who’s typical responsibilities were sweeping and changing bedding, but who did sewing and alteration work on the side as a source of additional income.

Similar to the first of the ‘gardener’s paintings,’ this canvas was prepared as if to become a standard painting. Early in the process, however, the canvas was torn into vertical strips meant to evoke the wooden paneling of gates.

Using paint, mud, cement and sand, the canvas was continually elaborated and washed. Once fully dry, the maid was asked to sew the strips back together, resulting in a piece that contains a sculptural form and clear reference to a three-dimensional object, despite clearly being made of otherwise two-dimensional canvas and paint.

It is not simply the fact that the semi three-dimensional canvas refers directly to a real-world object that makes the painting relevant. Most importantly, it refers more generally to the idea of a wooden gate that could very likely be visually similar to the entrance of the gardener or maid’s home - a gate that, in turn, stands as a testament to endemic social and political inequalities of access, wealth and power.

•

Perhaps most significant are the last three works that were produced. In the previous works, aestheticized markings stood in as references to larger cultural contexts. Even when the hand of the gardener or the maid was directly responsible for a final result, the visual display was still somehow mediated by some form of distance - the visual traces of the gardener/maid’s interaction was the result of a specific request for them to engage in the artistic process. Despite an attempt to refer beyond the context of making the artwork, the entire exercise was explicitly established within that context.

In the final three works, Jonathan prepared canvases as if to become regular paintings but then used them as if they were blank canvases. He lathered them with glue and pasted the canvases on the walls of a crumbling building. Once dry, Jonathan peeled away the canvases thereby pulling with them pieces of the walls on which they had been hung

Of significance is the nature and history of the building: it was once a home to a man who had recently passed away - an alcoholic who literally drank himself to death. The house stood abandoned and crumbling at the top of a hill in a humble neighborhood. There was not a single person in the community - neither child nor adult - who did not know the basic outline of the owner’s demise. Moreover, the fact that the house’s owner had suffered a painful death through alcohol abuse was always stated as a matter of fact (by children and adults).

As with the life of any human being, there are infinitely many details that cannot be fully accounted for, contextualized, explained and understood. But the fact that his home stood as a crumbling-but-permanent monument to his death and was consistently recounted as simple matter of fact, reflects a reality in which the community takes such a situation to be an ordinary part of life. The crumbing house does not simply represent the history and experience of a lonely and troubled man, but it contains within it the lives and realities of everyone in the community.

Certainly there is no way to shield a community and its children from all the perils of living, but it is a more than unfortunate circumstance when young children are confronted by the relentless decay of a decrepit building that so immediately represents a morbid death that is extremely near to them. It is unfair that they should be forced to consider (even if subconsciously) this gruesome reality as a possible part of their future - either through a similar fate of a relative or, perhaps, their own.

By incorporating actual remnants of this crumbling home into his canvases, Jonathan sought to conflate the aesthetic of the paintings (i.e., the look of crumbling walls) with the actual objects to which they visually referred. These final paintings do not simply look like crumbling structures from the surrounding neighborhood. They simultaneously look like and contain those crumbling structures.

And with those structures, comes not just a conceptual or metaphorical reference to the larger social and political inadequacies of the community and nation, but the actual weight of human loss and suffering that results from those inadequacies.

Despite the heavy nature of the paintings, the goal was not to politicize the work. Ultimately, the paintings are still meant to elicit an experience of beauty - however complex that may be - but they also help to serve as a reminder that art can help us restore a sense of balance and dignity to people who deserve it.

Mostly, they serve to remind us that, despite the injustice they often suffer, children deserve the luxury of being able perceive their lives and surroundings as beautiful.

-

1AMixed media on canvas • 63x63in • 160x160cm

1AMixed media on canvas • 63x63in • 160x160cm -

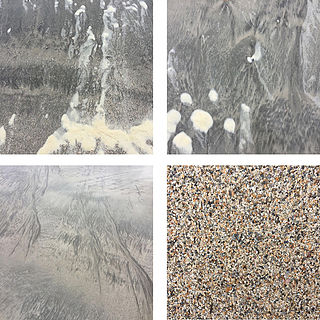

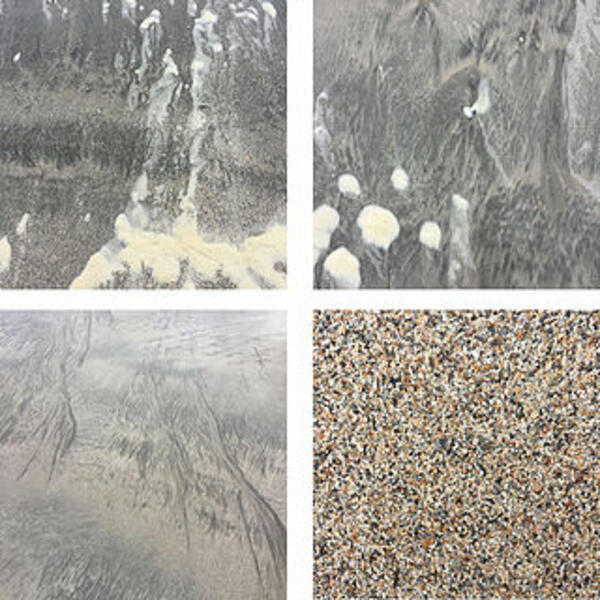

1BImages of washed sand beaches.

1BImages of washed sand beaches. -

2AMixed media on canvas • 63x63in • 160x160cm

2AMixed media on canvas • 63x63in • 160x160cm -

2BPainting Details

2BPainting Details -

House 1A woman stands in the window of her simple mud-brick home, next to her carefully maintained garden.

House 1A woman stands in the window of her simple mud-brick home, next to her carefully maintained garden. -

House 2A proud couple stands in front of the underlying strcuture of their nearly completed mud-brick home, which they are building themselves.

House 2A proud couple stands in front of the underlying strcuture of their nearly completed mud-brick home, which they are building themselves. -

3Mixed media on canvas • 63x63in • 160x160cm

3Mixed media on canvas • 63x63in • 160x160cm -

House 3A simple home, showing sigs of decay.

House 3A simple home, showing sigs of decay. -

4Painting Details

4Painting Details -

Wooden Gates

Wooden Gates

Immacualte Decay • Flawless Imperfection

With a slave history similar to that of the United States, Brazilians of African descent have suffered violent discrimination. Although much progress has been made, the scars of a painful history and unspeakable inequality are still present in Brazil. They are present in the streets of Salvador, Bahia and ingrained in its walls. It is this ongoing cultural story that I have captured in these two collections photography.

When I arrived at my new home in the historic district of the city, I was completely struck - if not bewildered - by the fact that the aesthetic I had developed (or, rather, that had emerged) in my silkscreen paintings was alive in the city in a completely organic and uninhibited way. I couldn't believe it.

Countless dilapidated and abandoned buildings peppered the city in various stages of decay. Although they represented a dysfunctional social and political system, I found incredible beauty in them. So much so, that even after a year of living there I could still be silenced by grace and beauty of an old dying building.

The buildings of the historic district, so beautifully multi-colored, are the result of a social process - not an aesthetic choice. Bahians are famous for their exuberance and flamboyant nature and it is shown in their rich and flavorful food, eclectic musical styles and their selection of colors. However, limited access to resources and the need to use low quality paint is not a choice. The result - after many seasons of chipped and weathered walls that have been colorfully painted several times over - is a strikingly beautiful display of light, color and texture that looks as if it were carefully crafted by the hand of an abstract expressionist.

Although overlooked by most, these buildings were treasures to me - they were unintended works of art that inspired me to put together these two collections of photography - one of decaying buildings, the other of an abandoned train yard.

While visually alluring, the aesthetic beauty of these photographs helps to communicate the larger cultural and historical reality that these visually stunning display are more than mere physical beauty. These images help us to understand those manifestations for what they are: an emergent complex social and political phenomenon.

-

Immaculate Decay 1Immaculate Decay 1

Immaculate Decay 1Immaculate Decay 1 -

Immaculate Decay 2Immaculate Decay 2

Immaculate Decay 2Immaculate Decay 2 -

Immaculate Decay 3Immaculate Decay 3

Immaculate Decay 3Immaculate Decay 3 -

Immaculate Decay 4Immaculate Decay 4

Immaculate Decay 4Immaculate Decay 4 -

Immaculate Decay 5Immaculate Decay 5

Immaculate Decay 5Immaculate Decay 5 -

Flawless Imperfection 1Flawless Imperfection 1

Flawless Imperfection 1Flawless Imperfection 1 -

Flawless Imperfection 2Flawless Imperfection 2

Flawless Imperfection 2Flawless Imperfection 2 -

Flawless Imperfection 3Flawless Imperfection 3

Flawless Imperfection 3Flawless Imperfection 3 -

Flawless Imperfection 4Flawless Imperfection 4

Flawless Imperfection 4Flawless Imperfection 4 -

Flawless Imperfection 5Flawless Imperfection 5

Flawless Imperfection 5Flawless Imperfection 5